Momentum and Greatness

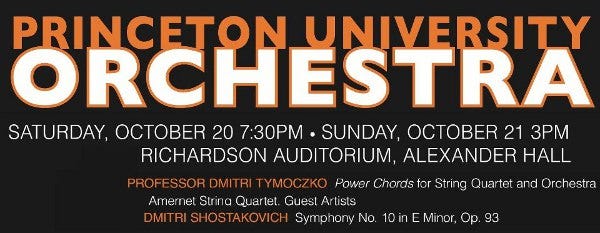

Princeton University Orchestra

Performing: Power Chords by Dmitri Tymoczko, ft. Amernet String Quartet

Symphony No. 10 in E Minor, Op. 93 by Dmitri Shostakovich

Oct. 21st at 3:00 PM in Richardson Theater

Free admission

If I may, I would like to preface this review by saying “Go”. At just under two hours, Princeton University Orchestra’s first concert this year is an ambitious effort that more than pays off for the listeners.

Tymoczko is an Associate Professor at Princeton whose compositions blend jazz, funk, and classical music, according to his short biography in the program. He is a modern composer. For those of you who appreciate all things modern, the orchestra’s first piece should be no hardship to listen to. For those of you who don’t, the results may be a bit more, well, unpredictable.

The concert begins with Broken Record, the first movement of Tymoczko’s Power Chords. True to its name, the piece stutters and skips and rewinds like your grandmother’s old record player still sitting up in the attic somewhere. It is the quartet that plays the melody in its pure form, echoed by the orchestra to produce an intentionally distorted, even warped effect. Still, the quartet’s notes are lovely and stirring. Swells of sound end in vacuums of silence, filled only by the soft notes of the Amernet String Quartet. The ending is abrupt, almost rude. The old gramophone is turned off, the record removed, and the days of careless dancing are once more given over to dust.

The second movement’s beginnings are ominous. Violin harmonics create an eerie atmosphere, though they quickly give way to some really lovely, longing notes. There is a nostalgic, rich feeling to Settlement that the crash and boom of Broken Record lacks. It is, perhaps, a more cohesive movement. But then the third movement’s glissandos and strange syncopation come together to give one the rather unpleasant sensation that the music is melting around one’s ears. This was, by far, my least favorite movement of the piece.

It’s not that Power Chords doesn’t have an idea, it’s that it has three of them. Three separate ideas that manifest in three, loosely connected movements, which is a shame. Tymoczko is a fine composer, but this was perhaps not one of his finer moments.

Listening to Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 brings a whole different level of aural pleasure. The first movement starts with an exposed cello soli. It’s easy for a section like that to come off hesitant or even weak, but the cellos handle the challenge masterfully. The solo clarinet’s entrance is sweet and smooth. Clarinetist George Liu ’15 is a real treasure for the orchestra, and it shows time and time again throughout the symphony. When the violins take over the melody from his solo, one is almost sorry to see the clarinet silenced.

Throughout the symphony, Conductor Michael Pratt’s command over the dynamics (especially the piano sections) speaks both to his ability as a meticulous conductor and to the orchestra members’ technical prowess. One of the few slips of the concert occurs just after the first pizzicato section. A few violins come in too early for their arco, but the mistakes are quickly swept away by the rest of the performance.

Other memorable moments in Shostakovich include first violinist Dean Wang’s ’13 solo in the third movement, which is quiet, understated perfection that commands attention without screaming for it, and timpanist JJ Warshaw’s ’14 performance in the second movement. Bo-won Keum’s ’13 oboe passage over the violin background in the fourth movement is something to marvel at — there is a sort of whimsical element to the way her notes sway and go as they please, unrestrained and totally free. The fourth movement may seem somber, but I would consider it more pensive — there is a thoughtful quality to it that is almost uplifting.

Princeton University Orchestra’s rendition of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 is driven and passionate. Their sound is rich and powerful, even as the complex runs demand technical perfection from the players. There is momentum; there is greatness.

Shostakovich, I think, would have been proud.