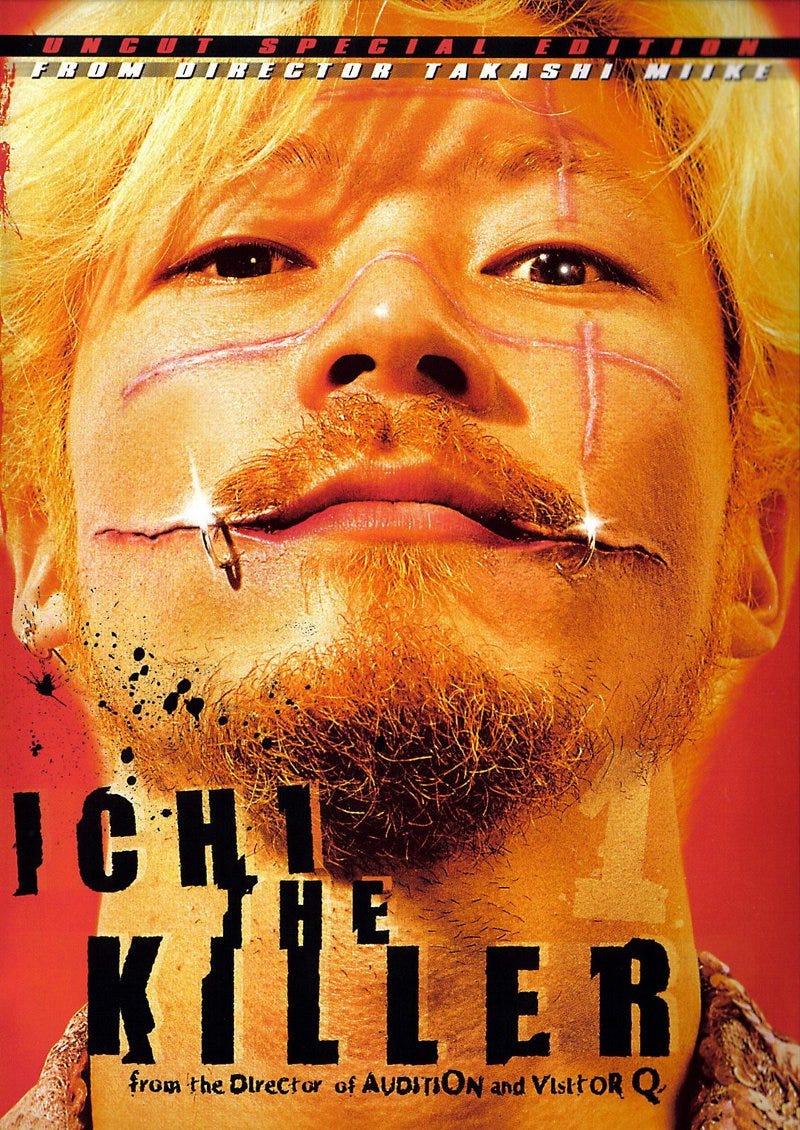

The Sadomasochist Within

Ichi the Killer

Directed by Takashi Miike

Starring Tadanobu Asano and Shinya Tsukamoto

Black Box Theater, Wilson

Hosted by the Major Choices Program and the Wilson College Film Society

Takashi Miike’s 2001 cult classic Ichi the Killer could not have been a more interesting way to entice underclassmen to become potential Film Certificate candidates. At the screening, held in the Wilson College Black Box Theater, attendees were treated to two hours of gratuitous gore, rape, gang warfare, and sexual deviance: policemen find themselves literally slipping on human viscera, prostitutes are brutally mutilated, a sliced-off human face slowly slides down a wall, countless interior surfaces are subjected to jets of absurdly high-pressure blood sprays from the necks of axe victims. More than one viewer left the room within the first fifteen minutes. The movie, needless to say, was an awesome journey into the comically disturbing and bizarre.

The story centers on the cool scar-faced Kakihara, a yakuza chief who looks like a hipster in a Joker outfit, and his quest to force an ultimate showdown with Ichi, the brutal killer responsible for the death of Kakihara’s boss Anjo, and who turns out to be a crybaby man-child in a buffoonish superhero costume. Along the way, gangsters are eviscerated by a hidden boot-knife, pimps get mutilated with knitting needles, and scalding oil is poured onto the back of an interrogation victim suspended from the ceiling by meat hooks in his back. We discover that the tough Kakihara was a queer masochist who enjoyed being beaten by Anjo, who despairs that with his boss gone, no one else could bring him the same painful pleasure as Anjo once did. A brief romantic tryst with Karen — Anjo’s sadistic girl who inexplicably expects other characters to understand her alternating Japanese, English, and Cantonese dialogue — leaves Kakihara utterly disappointed. As romantic as chains, blood, and punches could be, that is; the sequence with Karen happened to be the only consensual sexual scene in the entire film.

We find the source of Ichi’s violent outbursts: a bullied childhood and guilt over an adolescent episode where he watched a schoolgirl get raped without helping, due to his own arousal at the scene. Nearly everyone has one perversion or another. The only somewhat normal character, a henchman of Kakihara’s with an adorable ten-year-old boy, naturally has to get butchered in front of his son.

The violence is not tasteful, the gore is not artistic, the nudity is not sexy — the only time nipples are shown clearly on screen is right before they are about to be cut off with a razor in a torture sequence.

But that’s precisely the point. People who compare Ichi the Killer to Tarantino films miss the point. Tarantino aestheticizes violence; though Miike’s film, like Pulp Fiction or Inglorious Basterds, contains violence often to the point of comical absurdity, he intentionally de-aesthetisizes that violence with a relentlessly graphic realism. An illustrative scene has Kakihara, in repentance to his superiors for mistakenly torturing an ally, spontaneously cutting off the tip of his tongue with a katana. His bloodcurdling howls are interrupted by a call to his cell phone, which he calmly picks up, lispingly answers, and quits the room to meet his next appointment, leaving at least one of the hardcore yakuza syndicate leaders nervously fainting from the bloody antics. This is not a film of hesitation, circumspection, or half-measures. At one point, Kakihara berates an assailant, “Put some feeling into it, already!” as he lets the thug punch him without retaliation. “There’s no love in your punches!” After watching Ichi the Killer, no one can doubt the passion with which Takashi Miike delivers his violence.

Miike’s gratuitous gore is not without precedent — the film is based off a graphic novel that’s equally violent, but it’s a violence that’s quite common among Japanese manga. The average manga character typically seems to possess some fifty gallons of blood; Miike simply throws these bucket-fulls on white walls to show us what the cartoon violence would look in live-action. Only when we see the severed heads of gangsters littering the floor do we realize how pervasive the idea of blood for the sake of blood is in our media, not just in manga but concealed in sanitized, “aesthetic,” more socially acceptable depictions of violence. With the audience disabused of the euphemisms, with the conceit unraveled, Miike shows us who we really are. One watches the film already familiar with its reputation; one sits through it holding back the impulse to retch. Then the revelation comes. We, like Kakihara, are the real sadomasochists.