It’s Because They’re Dirty, You See

Apparently 2154 is set to be quite a party. Not only does James Cameron’s sci-fi tour-de-force Avatar promise us trysts with feral blue beauties in some distant galaxy; Neill Blomkamp’s sophomore feature Elysium assures us (and by us, I mean the illustrious cohort of future iBankers and oil moguls) luxurious golf-estate mansions and complete security from the riff-raff, right here in our own solar-system. Blomkamp’s vision of prosperity is, of course, manifested upon the life-supporting wagon-wheel of a space-station that is the eponymous Elysium; this vision haunts the earthen sky like a bourgeois spectre. Unfortunately, Matt Damon just can’t let a good thing be: he sets about trying to crash the gates of Elysium’s star-gated community, unleashing some ghastly genus of egalitarianism upon the world!

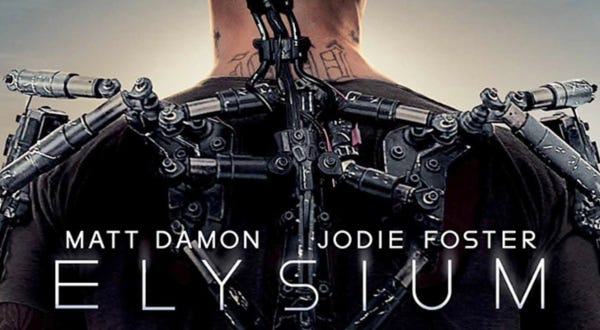

At least, that’s the view from up top. Down on earth, the situation is dire. The planet is over-populated, everyone is poor, and living-conditions are deplorable; health-care and infrastructure are practically non-existent. Even once-great cities like Los Angeles have fallen into ruin, their populations into subjugation. Malevolent robots incapable of empathy (but somehow quick to respond to any lip) patrol the streets enforcing compliance with a Kafkaesque bureaucracy. Living on the outskirts of this dystopian barrio-scape, we find Max de Costa (Damon), a downtrodden factory-worker and parolee. Since youth, Max has dreamed of escape to Elysium, together with his childhood-sweetheart Frey (Alice Braga). A freak factory accident exposes Max to a bumper dose of radiation, causing terminal illness. On Elysium, Max could simply climb into a panacean “Med Pod”, but on earth, he is beyond hope. Almost. Desperate and running out of time, Max scrambles to get to Elysium, on the way running into old friends, opportunistic criminals, government conspiracies, and even a chance for revolution.

Luckily for us, Elysium manages to convincingly present both of these perspectives in one film. Visually-rich landscapes, highlighted through many extreme long shots, together with clever CGI gadgetry and sweeping, mobile action sequences create detailed pictures of both of the two locational (and sociopolitical) extremes. These pictures demonstrate Mr. Blomkamp’s talent for perspective — a synthesizing talent, which enables him to embody sociopolitical and technological perspectives in atmospheric physical spaces. But these contrasting physical domains are themselves mobilized as if they were animate characters interacting with the narrative. Of particular interest in Elysium are the slums of L.A. — dusty and desaturated as anything; they form an especially poignant milieu for the film, and allow Mr. Blomkamp to once again display that nuanced understanding of the mise-en-scène of a shanty-town which so struck viewers in his debut production, District 9.

Naturally, that’s been the first question on everybody’s minds: how does Elysium compare to District 9? Poorly, most critics seem to think. The consensus in is that Elysium lacks District 9’s ingenuity, subtlety, and intelligence, although its big-budget visuals expand on District 9’s cinematic richness. Christopher Orr of The Atlantic concludes that, although “Elysium is a testament to Blomkamp’s extraordinary skill as a visual filmmaker, it does not speak nearly so well for his gifts as a writer.” And I can’t disagree that the plot has gaps or that its logic is jumpy. I have no idea why the President of Elysium can change with a reboot of “the system,” for example. But that wasn’t the most important point for me. I found the film’s themes and continuities more interesting, and I found it especially interesting to think about how Elysium follows up from District 9, which I maintain it does. You might call the two films two sides of the same coin, or rather, two views of the same scene. Because not only do both films pay unusual attention to social and political themes, they also both demonstrate that talent for perspective of Mr. Blokamp’s.

***

The similarities between the films start with their basic premises, or rather, with their basic premise, since — although it somehow has not yet been pointed out — they are just about the same. The protagonist becomes deathly ill, undergoes some sort of biological transformation, and in the essentially selfish search for a cure, instead discovers a broader social ill, requiring self-sacrifice to remedy it. Wikus Van de Merwe is infected by “the liquid” and turns into a prawn; Max De Costa suffers radiation exposure and consequently must be turned into a kind of cyborg. Both must subvert powerful economic and political interests and structures to regain health, as if MNU and Elysium were themselves part of a pathological world order, and as if the difference between individual and public health were imaginary. Blomkamp takes one blueprint and builds to its specifications several times, just within different settings and with different details.

Now one must concede, this doesn’t make him the most original of screenwriters. But it does mean that he gets to experiment — plant the same type of seed in different soils and see how it grows– and it does imply a focus on a recurring set of themes and issues. The central of these, it seems to me, is illness. This theme is introduced even more explicitly in Elysium than it was in District 9 (unfortunately sometimes too explicitly: see Defence Minister Delacourt…), but in both films, it does significant and poignant work moving characters and plots. This is absolutely nothing new, mind you– illness hasn’t been a novel theme at least since Sophocles. But District 9 and Elysium use the theme in a way which is novel for Hollywood. I can’t think of the last time I saw a big-budget sci-fi movie attempt to explore the tension between ontogenic and phylogenic social ills — or the last time I wanted to classify a movie in the box-office Top 10 as an attempt at Marxist epidemiology! And not only does Elysium imagine a future in which to investigate this theme, it also has a concrete historical model to reference. Like District 9, it can be read as an allegory for Apartheid.

Of course, any such allegory is definitely more oblique in Elysium than it was in District 9, not least because L.A. doesn’t resemble Johannesburg in any obvious ways. There is nonetheless still a clear South African element in Elysium — namely, the villainous South African mercenary Kruger (Sharlto Copley, a.k.a. Wikus van de Merwe) and his entourage — but again, this doesn’t obviously invoke any memories of Apartheid. Kruger is a more of a caricature: he’s what James Bond would fight if MI5 ever let up hating on Russians to instead pursue South Africans (maybe minus the cyborg parts). Watching Elysium in a Johannesburg cinema, I heard the audience produce several guffaws during Kruger’s appearances, which I’m not sure would be possible for an American audience. Quite simply, Kruger is a perfect Joburg goon: profoundly creepy, even debauched, but also “ ‘n boet”– “a bro”. Nowhere was this as clear as in his… eyebrow-raising rendition of the Afrikaans folk-song “Jan Pierewiet,” translated below:

Jan Pierewiet, Jan Pierewiet, Jan Pierewiet stand still!

Jan Pierewiet, Jan Pierewiet, Jan Pierewiet stand still!

Good morning my wife, here’s a kiss just for you,

Good morning my man, there’s coffee in the urn.

I think the South African’s response probably differed very little from everyone else’s after this one, albeit for different reasons: “Wha?…”

So, lacking obvious references, the landscape of Elysium at best contains a set of metaphors which we might gloss through the historical example of Apartheid. And one might say it isn’t hard to see a superficial comparison in the plot: Elysium is, after all, about a small minority holding the power and wealth, forcing the masses to live in squalor based on illusions of superiority. But I think that this analysis can be taken further.

First, note the difference between District 9 and Elysium that exists insofar as the latter lacks the theme of race-based discrimination that permeated the former, and replaces it with a class-based discrimination, a caste system, instead. But then recall that Apartheid was not only a system of racial discrimination, it was also a system of class entrenchment. The two kinds of superiority complex which buttressed white-rule were tightly intertwined. And it seems to me Blomkamp tries to bring this up: subtle biological overtones emerge in Elysium’s classism, overtones which bring the Elysian notion of class conceptually closer to race, to the extent that Elysian classism comes close to a species of xenophobia. Carlisle (William Fichtner), the compunctionless factory owner not even a Bolshevik propagandist could improve upon, seems at several points rather afraid of contracting poverty from his factory workers as if it were tuberculosis. “Don’t breathe on me,” he snarls at a dopey Foreman standing too close. I was reminded of the habit some people still have in Johannesburg of keeping separate cutlery and crockery for their domestic servants and “garden boys”– they’re dirty, you see, and their dirt is contagious.

Today, if it isn’t their race, it’s their poverty that makes them dirty. And this is not unique to South Africa: around the world, the rich erect neat little fences to enclose gated communities, quarantining themselves from the contagion of poverty. But in the mind of a South African director, I’d especially expect that Elysium’s version of classism feels like a compliment to District 9‘s version of racism; they’re conceptually related to begin with. What Los Angeles is to Elysium and what District 9 was to Johannesburg are together an expression of what Bophuthatswana was to the Transvaal, the Transkei and Ciskei to the Cape, and perhaps even what East Harlem is to the Upper East Side. And it’s no wonder when our contemporary class vocabulary is still not fully disentangled from the conceptual framework of social darwinism and its correlate ideas. Or put it Romney’s way. Why is it not our job to worry about the poor; why will we never convince them they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives? Because, the idea is, they’re that kind of people; it’s simply in their genes.

***

I guess I’m a fan of Neil Blomkamp’s new movie. If I had a penny for every MacGuffin in it, I could probably afford a ticket to Elysium myself– but I don’t particularly care. Elysium’s visuals and sense of place are not just products of impressive CGI: they’re products of thoughtful film-making. As Max De Costa looks up at Elysium from Earth and then looks back down at Earth from Elysium, so too do we look first up, and then down; but then also left and right at our fellow moviegoers. We’re just a little bit more conscious of class, feel just a little bit less content, perhaps even ill. It’s not often Hollywood produces a thoughtful movie for the mass market. Serious thinking about social issues — thinking that is actually engaged with a progressive and critical project — is today becoming not only increasingly unpopular but increasingly difficult. And you’re out of luck if you think you’re going to find it in The Fast & Furious or The Internship. At least Blomkamp tries — and for the kind of productions he makes, that’s already unusual.