How Lonely Sits The City, Part I

“Where were the world-renowned royal gardens? Where were the famed creations of the ingenious Chinese people?”

— Daocheng Weng

“But of her here now naught remains,

The light of her enchantment’s fled,

And all is darkness, emptiness;

All’s perished and to dust is fallen;

A bleak dismay now chills the blood,

And all alone weeps orphaned Love”

— From Derzhavin’s “Ruins”

“This little theory is tentative and could be abandoned at any time. Theories like things are also abandoned. That theories are eternal is doubtful.”

— Robert Smithson

I.

Why do ruins appeal to us? This question, which will guide the two essays that compose this series, is more central to our understanding of history and aesthetics than we may at first believe. The three epigraphs above are representative of a cultural and historical curiosity centered on the anomaly of ruination. As indeterminate monuments of time, decayed landscapes and architectural structures have fascinated and terrified academics, artists, and the broader public. Changing socio-political, economic, and aesthetic sensibilities have altered the interactions between ruins and their observers throughout time. The importance of historical context is not to be understated; although this essay is primarily concerned with exploring ruins as they exist (and have existed) in artistic and historical imaginations, I believe at least one conclusion can be made with little uncertainty. That is, our perception of any one ruin and its moral and cultural consequences are inextricably connected to its geographic and temporal coordinates. Our imagination of ruinscape, whether individual or collective, depends not only on who we are, but also where and when we are.

I was born in Detroit, a place of national and global attention that has been sufficiently mythologized as a symbol of capitalistic decline and racial implosion. Visitors and the media have also recognized the city as a site of great structural devastation. Perhaps my familiarity with the urban landscape numbed my perception of its retrogression. As an inhabitant of the city, I often acknowledged its architectural dilapidation merely as an unfortunate symptom of economic fallout. Rarely, if ever, did I invest these sites with aesthetic value. Although I was familiar with the work of Yves Marchand and Romaine Meffre — two French artists whose photographic documentation of abandoned locations throughout Detroit have achieved international notoriety — the notion of “ruin art” as ethically problematic never occurred to me.[ref]The photography of Marchand and Meffre will figure into an extended discussion of Detroit’s ruinscape in the final entry of this series. In this first part, however, I will focus primarily on three ruinscapes: Yuanmingyuan, Tsarskoe Selo, and urban New Jersey.[/ref] When I became aware of Princeton Art Museum’s exhibition New Jersey as Non-Site, I immediately recalled similar artistic trends in Detroit. In both cases, desolation appeared as a subject of contemplation. While meditating on urban ruination, I imagined the potential of a larger discussion that could address ruinscapes throughout history.

We know of Rome and Greece. Images of the broken Parthenon and the corroded Coliseum have endured as embodiments of former glory and democratic continuity. They stand in the highest echelon of cultural landmarks. The disparities between the Acropolis and modern urban ruinscapes are significant, as each location summons distinct intellectual and sentimental responses and encourages a particular kind of reflection (or, for the urbanized landscape, prediction). What lies in between classical triumphalism and contemporary woe? Here, I hope to address that. By scrutinizing the ways in which ruins appear in select works of art and in academic discourse, I would like to express the heterogeneity of the ruinscape. What follows does not profess to be an exhaustive survey of ruins. Instead, I have selected a few salient examples of ruinscapes that I believe can convince the reader that the ruin is a composite object of great complexity, perhaps one that defies accurate or enduring definition.

II. Yuanmingyuan

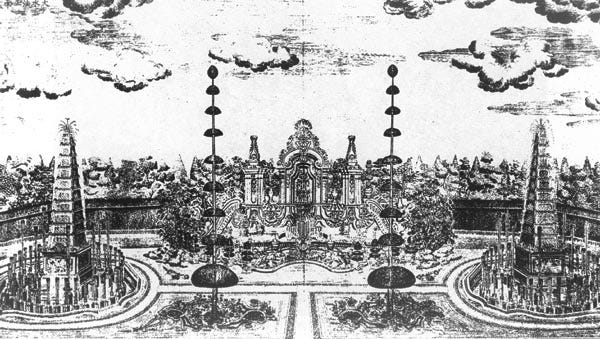

In 1860, Yuanmingyuan (Garden of Perfect Brightness; Old Summer Palace), a sprawling retreat in Beijing built for the Qing emperors, was looted and burned over the span of three days in an act of retaliation. During the Second Opium War, two British envoys, a journalist, and an escort of British and Indian troops had been sent to negotiate under a flag of truce with the Prince of Kung. The negotiators were taken prisoner, however, and tortured to the point of mutilation. Twenty British, French, and Indian captives died, while the two envoys were returned with fourteen other survivors. Lord Elgin, the British High Commissioner to China, responded by ordering the destruction of the imperial structure. The effort required 3,500 Anglo-French troops. In his narrative recounting of the war, British officer Garnet Wolseley described the burning of the palace:

Throughout the whole of that day and the day following a dense cloud of black and heavy smoke hung over those scenes of former magnificence. A gentle wind, blowing from the north-west, carried the mass of smoke directly over our camp into the very capital itself, to which distance even large quantities of the burnt embers were wafted, falling about the streets in showers…[T]he light was so subdued by the overhanging clouds of smoke, that it seemed as if the sun was undergoing a lengthened eclipse. The world around looked dark with shadow.[ref]Garnet Wolseley, Narrative of the war with China in 1860 (Harlow, England: Longman, 1862) 278–79[/ref]

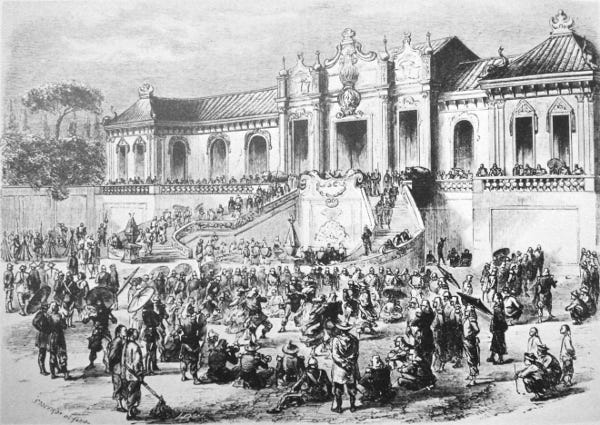

After the night of its destruction, this site of imperial grandeur was hardly recognizable. It was an apocalyptic scene wherein the landscape of the earth had acquired a permanent scar. The “very face of nature” had been transfigured, and the few surviving testaments to the palace’s existence were “some blackened gables and piles of burnt timbers”. Shorn of ornament and treasure, the palace had lost both its aesthetic and practical functions. The grand complex of gardens, pavilions, lakes, and hills that had made Yuanmingyuan a place of pastoral and mythic awe was consigned to the memory of those who had witnessed its grandeur, and would only later appear in the sketchbooks and photographs of interested observers. Still, even in its state of ruination, the mythology of Yuanmingyuan continued to inspire Wolseley. On entering the damaged gardens, he recalled “one of those magic grounds described in fairy tales.”[ref]Ibid., 280[/ref] Despite the forced transition from a state of orderly existence to one of ruptured dissonance, the gardens had retained their folkloric appeal. However, the suffering of the palace would persist. During the allied occupation of Beijing in 1900, trees in the surrounding landscape were torched, and the marble and tile interiors of the palace were plundered. Decades later, the ruinsite would assume new utilitarian functions as a location of animal farmsteads, factories, schools, garbage dumps, a colony, and a park.[ref]Haiyan Lee, “The Ruins of Yuanmingyuan: Or, How to Enjoy a National Wound” Modern China, 35 (2009): 155, JSTOR, 6 October 2013[/ref] These befoulments of the sacralized ruinscape would cement Yuanmingyuan as one of China’s most painful national losses.

Because the timber-structured, Chinese-style sections of Yuanmingyuan were easily consumed by flame, the ruins persisted primarily in the stone-based Xiyang Lou, the European-style gardens located on the northeastern edge of the complex. The presence of the Xiyang Lou allowed the palace to subsume western architectural traditions, which reflected not only the uncontested political power of the Manchu dynasty, but also the government’s freedom to indulge in the lavish pleasures of foreign creations. The “garden of all gardens” became an apt description for the ruins especially because, in their desolation, the European elements were emphasized more than they had been previously. The ruinscape of Yuanmingyuan exhibited the characteristics of a heterotopia, a utopic place connected to all other places that replicated and incorporated monuments which existed elsewhere.[ref]Ibid., 160[/ref] Foucault describes the heterotopia as a place that represents, contests, and distorts all of its emplacements. In effect, the cosmopolitanism of the gardens suddenly displaced the European architectural elements from their original temporal and spatial placements, aligning and reimagining them within the distorted topography of Beijing.

(Although I could not allow myself to digress too drastically in this discussion, I must mention an interesting contemporary trend in modern China. In her book Original Copies: Architectural Memories in Contemporary China, Bianca Bosker discusses the “simulacrum,” a type of imitative community found in multiple regions of China that replicates the architectural characteristics of such locations as London, Amsterdam, Venice, New York, and Paris. This peculiar phenomenon is a dramatic evolution of the kind of sham ruins featured in Yuanmingyuan. Supposedly, the development of simulacra came about when Chinese real estate companies tried determining creative ways to build residential communities. The allure of Western-like sophistication and economic advantage appealed to some of these companies, although domestic and international reactions to the sites range from frustration and mockery to confusion and anxiety (and, for some, aesthetic pleasure). This is not simply an act of appropriation, but one of replication that seems to be inconsistent with traditional hyper-nationalistic sentiments. How jarring it must be to encounter a 300-foot model of the Eiffel Tower surrounded by French apartments in the coastal Zhejiang Province. Even more surprising is the Venice Water Town with an artificially constructed canal, bordered by Italian villas. Although the simulacra are not ruins, the construction of these replicas threatens not only the borders of time and geography, but also the distinction between the “fake” and “authentic”. Now more than ever, China seems to be the heterotopic oddity that few people expected it would become. Indeed, Bosker writes, “While it once considered itself to be the center of the world, now China is making itself into the center that actually contains the world.”)

In the 1980s, more than a century after the palace’s destruction, a movement began to remodel the site into a park that would serve as both a national monument and revenue-producer. A critical concern for these restorationists was how best to reinstitute the ruinscape as a durable focal point of collective pride. Although memories of the site were anchored firmly in the Xiyang Lou, which were more emblematic of imperialistic permanency than national supremacy, it might have been possible to employ narratives of Chinese socialism to reconcile the otherwise incompatible elements of the ruinscape. Manual labor, for instance, figured prominently in socialist iconography. The narrative of the socialist rural landscape survived in descriptions of peasants and workers, and in the “vast vistas of undulating crop fields, extensive irrigation works, broad tree-lined roads, and shining farm implements.”[ref]Ibid., 162[/ref] The park was to be imagined as a beauteous site of history defined by its still-existent gardenscape, not as a national wound whose only indications of life were the solemnly standing pillars of a bygone era. The restorationists believed that to honor Yuanmingyuan as a milestone of Chinese civilization would require no less than the reconstruction of its fundamentally Chinese architecture. For some scholars, architectural novelty and beauty were synonymous. To allow the garden complexes to dissolve into wastelands would be to deny the ruins their function as totems of reverence and respect. Such individuals supported the partial renewal of the ruinscape so that the site could recall its aesthetic momentousness while also reminding the Chinese people of the foreign brutalities that had once been enacted there. Conversely, anti-restorationists objected that modifying the ruins would threaten the ideological-historical significance of the location. To beautify the ruinscape in any way “would amount to…covering up the crimes of the imperialists.”[ref]Ibid., 163[/ref] The ruins were to stand as they were, accents to their own irreparable wretchedness.

To render the wreckage of Yuanmingyuan as the antithesis of a national wound, restorationists recalled an ideal of Western architecture that emphasized the beauty of edifice in relation to surrounding natural elements. One Chinese horticulturist praised the reconstructed ruinscape as a location that would rival the Disneylands of Japan and the United States.[ref]Ibid., 166[/ref] I can think of no more explicit conjunction of ruin and mythology than this. Dissenters of the “Disneyscape” mourned the distractions of souvenir shops, staged photo sessions, food stalls, and tour guides that characterized this foreign pageantry. The spectacularization of the site might have neutralized the aura of tragedy that many anti-restorationists wished to preserve. Robert Ginsberg, a renowned documenter of ruins around the world, described one’s encounter with the ruinscape as “inherently awkward and ambiguous”. Because the ruin has no practical purpose, he believed, what the visitor hopes to achieve is necessarily unclear. In the Disneyscape that Yuanmingyuan had since become, however, the site could successfully fulfill a practical purpose by educating visitors of its history using brochures and staff-led tours.

Whether the Disneyscape could be an acceptable model of public participation was unclear. Some scholars and artists have argued against this paradigm. As Andreas Schonole notes, the commoditization of ruins “conceals our participation in the relentless logic of economic expansion and deprives us of our ability to imagine an otherness that could be more than entertainment.”[ref]Andreas Schönle, “Ruins and History: Observations on Russian Approaches to Destruction and Decay” Slavic Review, 65 (2006): 654, JSTOR, 6 October 2013[/ref] Thinkers along this strain preclude the sociability of the ruin site and lament the motivation of monetary gain. The economized ruinscape inhibits catharsis by removing the opportunity for solitary observance and transplanting in its place the phenomenon of communal reflection. In a three-part poem cycle entitled “Three Laments at Yuanmingyuan”, Wang Xigen expresses his horror at sacrilegious (distracted) tourists. He imagines the surviving pillars as “ancestral bones of the nation, stripped, gutted, and corroded, crying out their testaments to their descendants.”[ref]Lee 179[/ref]

If the ruinscape is a mausoleum wherein lie the sacred memories of one’s progenitors, then tourists exist only to desecrate these grounds. Perhaps even worse is their potential to distort and replace these memories with photographic and multimedia records. Haiyan Lee notes that visual representations of the park often highlighted its heterotopic qualities, where observers could discover the residual evidence of a great clash: the magnificent empire of China at odds with its strange Western destroyers.

For Lee, the heterogeneity of the ruins — as well as its influence on the imaginations of artists — appears to be unproblematic. As a frequent visitor of Yuanmingyuan, he noted the ways in which spectators would interact with the ruins, a group of females “imagining themselves as palace ladies holding aloft lotus lanterns, vying to be the first to be greeted by the emperor seated in the center pavilion.” Meanwhile, those who valued a private experience could “linger quietly amid the rubble and perhaps carve out a line or two [of poetry] on the numerous stone fragments lying about.”[ref]Ibid., 169[/ref] What distinguishes the physical ruin of Yuanmingyuan from visual or poetic representation is its very spatiality. Here, visitors can interact with the remnants, literally inscribing themselves onto the suspended history of the broken palace. A place once perceived as a wound can become the medicine that restores the injured national body. In some ways, then, the Chinese ruins encourage both a collective amnesia and individual recollection. Although any historical truth may be lost (and, if not erased completely, then preserved tangentially in pictures, sketches, and first-hand accounts), the site summons the citizen to project her own vision of the past onto its body.

Thus, the ruins imbibe new identities and let the spectators assume new forms as well, namely the roles of actor and historian.

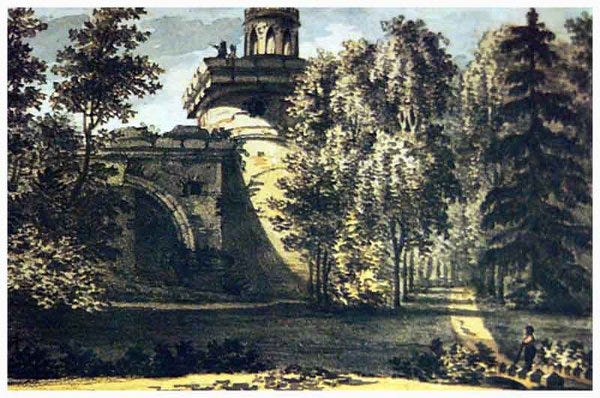

III. Tsarskoe Selo

Upon the death of Catherine II of Russia in 1796, her son and successor, Paul I, acted to ensure the erasure of her memory. Members of her court were exiled, and the palaces and sculpture gardens that had been erected during her reign were largely neglected. Austere, militaristic buildings supplanted the glamorous structures of Catherine’s court. Paul’s abandonment of his mother’s monuments was interpreted as creating the first genuinely Russian ruins.[ref]Luba Golburt, “Derzhavin’s Ruins and the Birth of Historical Elegy” Slavic Review, 65 (2006): 671, JSTOR, 6 October 2013[/ref] Although stone works of the medieval period were discovered in the 18th century, these were not perceived as native monuments, possibly because they had been fashioned after Greco-Roman models. This supposed dearth of authentic ruinscapes encouraged a search for national domains of sentimental and historical importance. The “sham ruinism” trend developed rapidly, as is embodied by the imperial park in Tsarskoe Selo (modern-day Pushkin), the tsar’s favorite summer residency. As one who sought to exemplify the European monarchy, Catherine ensured that the landscape of Tsarskoe Selo reflected the most recent European developments (English gardens, artificial ruins modeled after the Roman tradition, etc.). In response to the sudden and jarring dereliction of the imperial palace, the populace began to project its own fantasies on the depopulated space. As witnesses to the Catherinian era’s transition from contemporaneity to history, Russian citizens could memorialize and aestheticize the royal ruins in any way they wished. In short, the people could both create and enlarge a Russian historical mythology.

Catherine’s attachment to the architecture of her Roman predecessors allowed her to fabricate a cultural genealogy linking the antique world with the modern Russian empire. The Cameron sculpture gallery in Tsarskoe Selo, which recalls for me the Ionic Temple of Athena Nike, housed eighty statues of Russia’s ancient and modern military and intellectual heroes. Another structure, Catherine’s Doric Column, sought to unite Greek and Russian antiquity. The structure is half-unearthed while a Turkish-style summerhouse stands over it, symbolizing ancient Greece’s subordinance under Ottoman rule. Coincidentally, Russia would eventually conquer the Turks. The placement of the column and summerhouse on Russian soil, then, emphasizes the incorporation of architectural elements of Greece and Turkey. Exhibiting these monuments within the Russian empire displaces the two countries as the beau ideals of the eastern world and positions Russia in their place. Paul’s digression from the Enlightenment models of architecture, however, threatened to dissolve this genealogical bond, which would only delegitimize the predominance of Russian society.[ref]Ibid., 673[/ref]

Paul’s sudden ascension to the imperial throne was a sort of rupture in itself. His mother’s reign was a prosperous one during which the country achieved militaristic fame, and there was no guarantee that he would be able to meet the standards she had set. One poet who gained praise for his poetic memorializations of Catherine’s reign was Gavriil Derzhavin. His great odic work, “Ruins”, places the tale of Catherine the Great within a mythological setting on Cythera’s inlet, the island of the love goddess, Venus. The poet’s evocation of Catherine’s court is dreamlike, and it utilizes architectural elements to recreate “a dynamic world of incessant activity.”[ref]Ibid.[/ref] Although Derzhavin rendered the tsar’s story in a fantastical landscape, Russian readers would have recognized the grottoes, streams, menagerie, and other emplacements of her court. They also would have identified the thin allusion of Catherine as the love goddess, which only aggravated the melancholy inspired by her disappearance. In Derzhavin’s poem, the post-Catherinian world exists in a state of dolefulness. To juxtapose the past and present, Derzhavin renders the circumstances of Catherine’s rule in great detail, thus blurring the division between his role as historian and fable-maker. On one hand, references to actual locations and events could be interpreted as accurate historical exposition. On the other, the poem seems to be a tribute to the empress-god, a chimerical entity that synthesizes Russian history and Roman folkloric tradition.[ref]Ibid., 677[/ref]

In the poem, Derzhavin guides the reader through the space of Tsarskoe Selo, recounting the empress’ daily activities until the encroachment of foreboding “Night” — a symbol of Tsar Paul’s dark arrival on the throne. This style of presentation allows the reader to occupy the same physical-literary space as Venus, which disorients one’s perception of time; either we are drawn back into the historical fabric, or the empress-god rises to meet us in the present-day. The misalignment of time also displaces the architectural structures through which Venus is passing over the course of the day. The effect is temporally and spatially absurd because it disrupts the linear model of time, instead forcing us into a flux state that is both uncomfortable (it confuses our sense of historical propriety) and serene (we are in the presence of a gentle god). The empress-god begins her day in solitude, like the reader, pondering governmental institutions and the citizens of Russia. This contrasts with the latter half of her day, as she contemplates the military activity of her people. Derzhavin invites the reader to recall the victories of Catherine’s generals by observing her introspection of war monuments. Whether the reader is to be a quiet witness or a vocal lamenter is unclear.

While inspecting the monuments, the fictional Catherine focuses more on the inscribed depictions than on the architecture itself. Historical set pieces become more important than the physical spaces on which they are memorialized. Furthermore, the opposition of the playful love goddess and representations of violent warfare complicate the historical narrative that the poem seems to both summon and reject.[ref]Ibid., 681[/ref] The Catherinian ruin “invited its beholder to contemplate military victories in a pastoral setting where the memory of war violence was mediated by monumental form.”[ref]Ibid., 682[/ref] Here, the monument acts as a locus of historical transformation. It hinges upon the dichotomies of militarism and tranquility, human and god, worn ruinscape and pristine pasture. Our access to a historical moment is available through Venus’ eyes and is, therefore, limited. In the hybrid form of the empress-god, the omnipresence of the divine becomes irretrievable. We are therefore left with the mortal Catherine, whose frightening disappearance renders us sightless.[ref]Ibid., 684[/ref] Neither the potential aestheticism of the old monuments nor the details of history are visible. Indeed, the line between dichotomies seems to disappear and, in our blindness, we cannot know what spaces we inhabit or what forms we may assume. I am recalling an old Gnostic interpretation of eclipses. It was the Manichees who believed that an eclipse occurred when the sun and moon veiled the eyes of man from the cosmic battles happening in-between the light and dark. Time and change continue even in our blindness. If we wish to restore our sight and see the sun again, our only option is to remember the things we saw in the past, to forget the plight of the gods.

Having been consigned to the past, Catherine’s reign may only persist in one’s memories. If the poem offers any semblance of hope, it comes from the poet’s ability “to reassemble the queen’s symbolic body [through the act of remembrance] despite the violence it suffers.”[ref]Ibid., 685[/ref] The Russian people could adopt the role of historian and healer, soothing the incoherent ruins with their own constructed fables. Derzhavin’s historical ode creates a “collective remembrance” in the same way photographs and videos memorialize the Old Summer Palace. Due to the poet’s vivid reimagination of Tsarskoe Selo, the present becomes “the moment of greatest visibility”, in spite of Paul’s usurpation. Derzhavin’s authoritative position as the poet-historymaker lets him establish a definitive vision of the empty space and its mythical inhabitants. Only this image, which has been irrevocably distorted, survives. For Derzhavin, the ruins of Tsarskoe Selo became a site for storytelling, the creation myth of a new historical genealogy. For the citizens of Russia, history could finally become a space for personal reflection.

IV. New Jersey

In a 2010 article for The Nation, Chris Hedges describes the environment at “Transitional Park”, an encampment site of blue and gray tents that provides shelter for some of Camden’s homeless population.[ref]Chris Hedges, “City of Ruins,” The Nation, 22 November 2010: TheNation.com. 6 October 2013[/ref] The park was created by Lorenzo Banks, who claimed to be a Vietnam vet, former heroin addict, ex-convict, and survivor of a failed suicide attempt. At the time, Camden had more than 700 homeless, but the county only provided 220 beds, so public safety officials tolerated the tent city despite its illegality. Banks purchased about forty damaged tents from Wal-Mart and Kmart at a reduced price, repaired them, and set them up as shelters. Transitional Park had a population of approximately sixty people whose ages ranged from 18 to 76. To maintain order, Banks conducted weekly tent inspections, organized group meetings, and posted a list of sixteen rules on plywood, which hung precariously on a tree. The rules covered issues concerning fighting, trash pick-up, drug use, and other relevant concerns. Residents would receive two warnings for infractions before they were evicted. At night, someone would always stand guard. If I were to align Transitional Park with a fictional setting, I might point to the survivor settlements scattered throughout Atlanta from The Walking Dead comics. Eventually, the police dismantled the site, and the homeless inhabitants returned to the city streets.

I don’t know whether we should compare Transitional Park to a post-apocalyptic counterpart, though. We enjoy the entertainment series by virtue of its irreality. The circumstances of the narrative are fictive, regardless of how much we revel in its horror or sympathize with its broken characters. However, the story of Camden — and other urban landscapes — is woven into a real and often tangible historical fabric. Its tale is very similar to that of Detroit. Camden has a population of about 70,400 and is one of the poorest cities in the nation. The real unemployment rate is projected between 30–40%, and the median household income in 2010 was $24,600. There is a 70% high school dropout rate and only 13% of students pass the state’s mathematic proficiency exams. Hedges writes, “Camden is where those discarded as human refuse are dumped, along with the physical refuse of postindustrial America.”And, indeed, vestiges of a mechanized economy still stand across the city. Windowless brick factories. A trash burning-plant that releases noxious clouds. Immense piles of scrap metal that wait to be fed through a giant shredder. The city is also “scarred” with thousands of decaying, abandoned houses and overgrown lots littered with garbage and tires.

The present vision of Camden is a breach from its former eminence. It was once an industrial giant, a sort of metonymical representation of America itself. Just as the Willow Run bomber plant employed some 42,000 workers at the height of the Second World War, Camden’s shipyards employed 36,000 workers who constructed some of the country’s most impressive warships. Since its boom era in the 1950s, though, Camden has lost forty percent of its inhabitants. There are no movie theaters or hotels, and the one supermarket is on the city’s outskirts, away from known areas of crime. I find it remarkable that, while researching ruinscapes, most of the sights I discovered were bemoaned because they had once embodied a particular aesthetic, political, or cultural function. The magnitude of their deformation was made all the worse because their fall from grace was either unexpected or, as is the case for many urban ruinscapes, painfully slow.

Hedges identifies Camden as “a warning of what huge pockets of the United States could turn into as we cement into place a permanent underclass of the unemployed.” Such statements reveal an anxiety that casts the depoliticized urban landscape as an omen of a future condition. The ruin of Camden is inextricably bound with its political corruption and pecuniary misfortune, neither of which seem to be easily amendable. The crumbling face of the city cannot exist in a “mute materiality” separate from its historical narrative. Professor of American Studies Nick Yablon discusses the significance of the future anterior tense in conversations about urban ruination. The construction “will have been” allows one to contemplate the city “from the horizon of some kind of aftermath.”[ref]Nick Yablon, “The Metropolitan Life in Ruins: Architectural and Fictional Speculations in New York, 1909–19” American Quarterly, 56 (2004): 333, JSTOR, 6 October 2013[/ref] This speculative temporality signals time itself as running simultaneously forward and backward. Thus, the city becomes “modern and archaic, an object of both anticipation and retrospection, a site for futurology and archaeology.” The illogic of the future anterior unravels time as we conventionally understand it, and ruins exist insomuch as they maintain their dual nature of growth and decline. The moment one interferes with the “natural” progression of a ruin by preserving them (restoring, memorializing, etc.), the identifier of “ruin” no longer pertains. Perhaps the most compelling characteristic of the ruinscape is its apparent rejection of the present. A ruin cannot be now; it is, instead, both before and after us, and it will always have been so.

In her essay on New Jersey as Non-Site, the most recent installation in Princeton’s Art Museum, curator Kelly Baum signifies urban New Jersey as an important ground for postwar artists. New Jersey’s identity, she argues, has always been defined in relation to the metropolis of New York City. The state was an “other” on the margins of a cosmopolitan core. Social and economic changes (such as those that brought Camden to its current state) destabilized New Jersey’s landscape, marking it with such “temporal absurdities” as an unfinished suburban house next to a dilapidated brick factory. For artists who valued the incongruities of urbanity, New Jersey appealed as a place for experimentation. Scenic vistas, such as the kind afforded by the Delaware Water Gap, were largely avoided. Instead, these artists used as origin points New Jersey’s “crumbling cities, exhausted mines, industrial ruins, and polluted beaches.”[ref]Kelly Baum, New Jersey as Non-Site (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Art Museum, 2013): 27[/ref]

Allan Kaprow, a painter and assemblagist, developed the idea of the “fertility of desolation”, an artistic philosophy that extols the urban ruinscape as a site of potential growth, not one of dejection. Artists such as Nancy Holt and Dennis Oppenheim represented severe disjunctions from the pastoral in their work. To document a transfixing series of rituals entitled Mythologies, performance artist Charles Simonds and a camera operator trekked to the clay pits of Sayreville. The pits were home to the Sayre and Fisher Brick Company, once the most productive brick factory in the country. When Simonds arrived in New Jersey, only one clay pit was still active. The site became a “repository for fantasy” wherein Simonds could literally rise from the earth in a gesture of rebirth.[ref]Ibid., 28[/ref] The artist, stripped of his clothes, rolled in the clay and packed mounds of it onto his body. He carved a miniature city on his stomach and, in one compelling image, an unmoving Simonds resembles the messianic Christ figure. In this ahistorical wasteland, man does not resist the surrounding devastation, but instead comes directly from it.

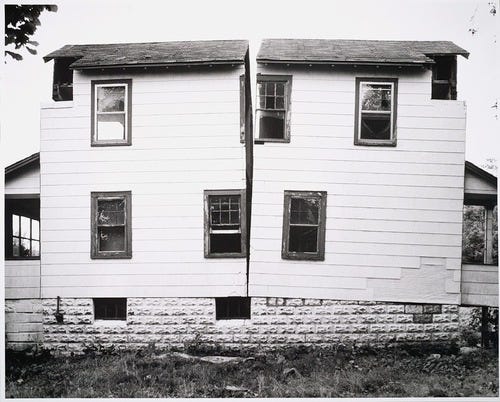

Gordon Matta-Clark’s Splitting is, frankly, one of the reasons I decided to write about imaginations of ruinscape. The image above shows the “building cut” that Matta-Clark (who, ironically, studied architecture) and a few of his friends performed on a disused home in Englewood. The men made two parallel cuts one-inch apart along the middle of the house’s lateral axis (from the roof to the bottom of the floor), dividing everything in its path. Once the artists chiseled away the cinderblock foundation, they tilted one-half of the house back and down. The result was a bastardized and distorted structure almost entirely unrecognizable in comparison to its original spatial construction. The building is something from a fantastical horror tale, and the historical continuity of the house is disrupted by the violent engineering of an alternate form. Now fractured and bereft of its original identity, the house may even belie the nomination of “ruin”. It has been artificially deconstructed into a cinematic, interactive experience. This “negative architectural activity” redirects the space onto a different temporal continuum. According to artist Robert Smithson, the loss of energy peculiar to a deconstructed site corresponds to a loss of stability, coherence, and harmony. The reorganization of space “diminishes our ability to perceive or comprehend”, and it is no longer sufficient to rely on sight alone.[ref]Ibid., 32[/ref]

Many of the avant-garde artists of the time addressed the absences that could be perceived in postwar New Jersey. The “non-sites” invert or nullify the geographic and temporal placements of both the location and spectator. These artists seemed to be intrigued not merely by ruination and its aftermath, but also “the area in between them”. If anything exists between structure and void, they wished to discover it or, at least, to become aware of it. Until that moment, these sites would stand as things divested of their former selves but not yet possessing new identities. The intrusion of the artist complicates a ruin’s ability to forge an identity by influencing the way a site is perceived. The projects of the New Jersey artists used otherness “as its subject and instrument” and, in doing so, crafted a narrative of perpetuity whose conclusion was unlikely to be determined.

***

Kevin Coyne tells the story of the Jersey Shore he knew as a child, before and after Hurricane Sandy:

At the end of Pompano Avenue in Manasquan, one of the Jersey Shore towns scoured and tumbled by the storm, is a small patch of beachfront property that seems as if it has been in my family for several generations now. We hold no title to it, other than whatever property rights might accrue from the thousands of summer days we have spent there at the ocean’s edge. It is 17 miles from the inland town where I grew up and still live, a rectangle of sand just wide enough for a couple of towels and long enough for a few chairs. It is where my mother and father took my siblings and me when we were children, and it is where my wife and I took our own children.[ref]Kevin Coyne, “My Jersey Shore, Now in Ruins,” New York Times 2 November 2012, 3 October 2013[/ref]

Their summer home, now in ruins, has not been erased from memory. “Habits die hard,” Coyne writes, and he cannot imagine not returning to Manasquan. Although it isn’t the closest beach to his home, “it’s the one where everyone has always gone.” The family migration to the site is rooted in history, inspiring memories of weekend trips “along a potato-train line that hasn’t run in almost a century”. There is no boardwalk along the beach, which had been abraded into a “narrow strand”. The sand was pushed away into the streets behind, as though an earthquake had struck. When Coyne and his family looked to the north, however, they saw something they hadn’t seen in years. A once-buried wooden jetty that Coyne recognized from his favorite photograph of his father. In the photo, Coyne’s father watched as his toddler son approached the water. Now, in this new image of the present, the jetty stood alone, “like a guidepost, marking the way back.”