What We’re Loving — February 2014

Image courtesy of mothbook.org, McPherson & Company, and Annapurna Pictures.

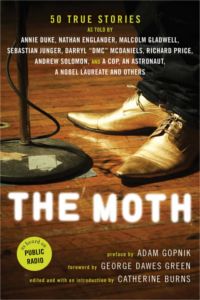

I’m loving the radio in print. I just read The Moth, an anthology, edited by Catherine Burns, published last year of fifty true stories told live sometime since 1997, when George Dawes Green held the first Moth performance in his New York living room. In the past decade The Moth has found its voice helping storytellers, from rapper DMC to astrophysicist Janna Levin, find their own. The Moth Radio Hour is encoded into my weekly routine- I never don’t want to hear a story. The style of a Moth story is casual, intimate, nakedly honest- these are the stories you tell at dinner long after the table’s been cleared, the stories you tell on your roommate’s futon when your socks are off and it’s too late to feel tired. Reading these kinds of stories on a page let me slow down and see just how we use words when we aren’t trying to hide behind language, when we just have something you’ve got to hear.

– Will Lathrop

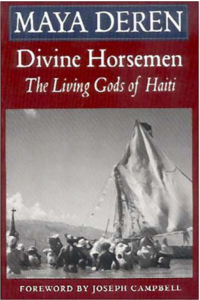

“Myth is the twilight speech of an old man to a boy.” Thus experimental filmmaker Maya Deren inaugurates Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, which is at once an anthropological study and poetic exegesis of Haitian Voudoun, a religion practised primarily in the motherland. Although the book was published in 1953, Deren lends herself to an enduring project of self-surrender in the West Indies. She injects her prose with considerable insight into a critical component of Haitian culture, revealing a surprisingly mature voice (she was in her late 30s at the time) to her exploration of mysticism and spirituality in one quiet sector of the world. One can see the guiding hand of Deren’s editor, Joseph Campbell, as she navigates the complexities of vodoun, which has often submitted itself to popular criticism and derision. Deren wishes to kindly dismiss these animadversions, as she herself participates in rituals of dance and spirit possession, commenting on them as would an invested companion. Deren writes, “I end [the book] by recording, as humbly and accurately as I can, the logics of a reality which had forced me to recognize its integrity, and to abandon my manipulations.”

I have read of the many loa, spiritual intermediaries between Bon Dieu (the Creator figure) and the serviteur (a practitioner of the religion). Deren commits much of her time to explaining the roles of each loa in the lives of Voudoun adherents. These spirits, which cannot quite be called gods, have distinct personalities and preferred offerings, summoning rituals, etc. Last night I read of the charismatic Ghede, Lord of Eroticism and Death, who can restore the dead and sick, transform man into beast, grant life and wisdom to those in need. The book is populated by such figures — Simbi, the patron of magicians; Agwé of the Sea; Ogoun the warrior hero and statesman. Deren dares not travesty these spirits, which for many Haitians reveal as much as can be known about the natural world.

The physicality of the summoning rituals (led by houngans andmambos, which we might call priests and priestesses) is a kinetic expression of the Haitian metaphysic. The mythology of these “divine horsemen” — a name which comes from a proverb translated as “Great gods cannot ride [possess] little horses [serviteurs]” — does not belie their existence. Rather, it reveals the vast ancestral heritage of a pratice frequently designated as sensational melodrama. I found when reading the text that the origin stories of Voudoun, which has assimilated Catholic iconography for its own purposes, indicate a culture unbound from the trappings of systematized religious institutions. Their beliefs are perhaps the richer for the great creativity and novelty of their patron spirits. It is a read for anyone interested in representations of the spirit, one that I will likely revisit very soon.

– Aaron Robertson

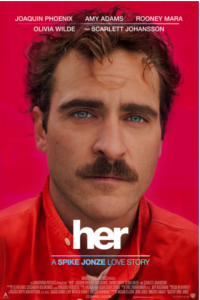

Thoughtfully unraveling, tenderly acted, and gorgeously shot, Spike Jonze’s “Her” (2013) tells the story of Theodore, who falls in love with his computerized personal assistant, Samantha. The third main character of the film, however, is Her’s soundtrack. Near the end of January, Jonze released the 40-minute score online, and I haven’t been able to stop listening to it since. Composed by indie rock band Arcade Fire and Owen Pallett, the score’s tracks range from the tense, synth-based “Milk & Honey” to the poignant piano solo “Photograph” (my favorite). Whether it’s accompanied by the film or playing on its own, the music captures the pensive complexities of love in this day and age.

– Whitney Sha