FROM THE ARCHIVES: Interview with Jonathan Safran Foer (2004)

“Jonathan is a naturally gifted young writer who would have flourished in his own idiosyncratic way without the aid of any writing instructor. As an undergraduate he was a delight to work with and has become, since graduation and the warm and widespread positive response to his novel, a friend whose imagination continues to surprise and delight.”

- Joyce Carol Oates

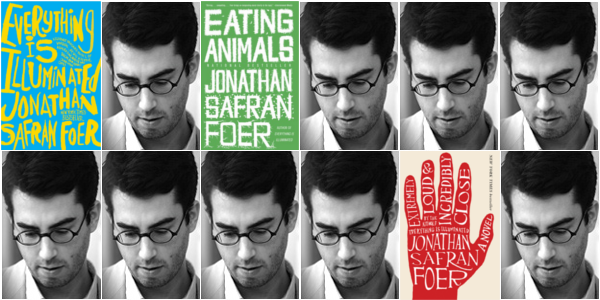

[Jonathan Safran Foer graduated from Princeton in 1999. Developed from his creative thesis, Foer’s first novel, Everything is Illuminated, was published in 2002. His second novel, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, was published in 2005. In 2009, Foer published his first book of nonfiction, Eating Animals. In June 2010, The New Yorker included Foer on their “20 Under 40” list of twenty fiction writers under forty years old who they believe “are, or will be, key to their generation.” In August 2010, in a piece for the Huffington Post, writer and critic Anis Shivani included Foer on his list of the “15 Most Overrated Contemporary American Writers.”]

***

On December 5, 2004, the Nassau Literary Review traveled through a blizzard to Brooklyn to meet with Jonathan Safran Foer. We got a table at the 2nd Street Café, where the walls were plastered with schoolchildren’s drawings. Over pecan pie, we talked about what writing means to him.

Nassau Literary Review: Can you talk a little bit about the process of writing your creative thesis? How did the advising process work for you?

Jonathan Safran Foer: I had written about half of it before my senior year, so the process was about editing as much as it was about creating new things. Or maybe there’s no difference. I’d meet with Joyce once every two weeks and we’d sit in her office and talk. She was very honest. Brutally, at times. In retrospect, I’m more grateful for her brutality than her praise.

NLR: You were a philosophy major. The philosophy department let you write a creative thesis?

JSF: No, I also wrote a philosophy thesis. But it wasn’t particularly good work.

NLR: How did you have time to do that?

JSF: Because it wasn’t good work. I put it off as long as possible, and did a half-assed job. Fortunately, my advisor, Gideon Rosen, was nice enough to let me follow my passion. Actually, he ended up providing a lot of great advice for the novel.

NLR: What made you decide to go for it with the book? Many people who write creative theses, although they do continue writing after Princeton, abandon their thesis project.

JSF: I never really thought of it as my thesis project, because I had been working on it before, and I knew that I was going to continue to work on it. I liked it and I didn’t want to let it go yet. I also had encouragement, particularly from Joyce, to keep going with it.

NLR: So what did you think about Princeton in general?

JSF: I had a great experience … I think I had a lucky experience. If I hadn’t gotten involved in the writing program, I probably would have had a hard time. Actually, it was my saving grace.

NLR: How did you feel about the end product of your thesis?

JSF: I don’t remember. I’m sure that I would never want to look back at my thesis. I don’t ignore the fact that I wrote it, but I’d never want to look back at it.

NLR: What did you intend to accomplish with the book?

JSF: That’s what my philosophy thesis is about: the role of an author’s intention in any reading of a book, and with what regard that’s to be taken. You think my book is about one thing, and I think my book is about something else. Who’s right? Or is neither of us right?

NLR: Why did you change the title of your thesis, The Book of Antecedents, to Everything Is Illuminated?

JSF: I always liked The Book of Antecedents. The only problem is that “antecedents” is such a dippy word. No one gets fuzzy for “antecedents.” Everything Is Illuminated is warm. I’ll always take warm to dippy.

NLR: It’s something the reader can hear Alex, you the author, and Jonathan Safran Foer the character saying. Speaking of which, do you think it was a bold move to name a character in your first novel after yourself.

JSF: I don’t think about it anymore. I was glad I did it at the time, but I don’t know that I’d ever do it again.

NLR: Some readers would say it makes the story appear self-conscious. Do you think you wrote the novel like that to show your freedom from self-consciousness, because you were self-conscious, or both?

JSF: Or neither? (Laughs.) It was really never a decision that I made, and it never even occurred to me that I was doing it. I just did it — it was the only way it could be done.

NLR: In the novel you focus a lot on the interaction between image and text. For example, the design of the cover and the icons that introduce each chapter.

JSF: I’ve always loved visual art. I probably go to that for inspiration more than I do to literature. I always want the experience of reading my writing to be more like looking at a piece of art than reading a book. What I’m working on now is even more visual.

NLR: In one of her lectures on the novel, Elaine Showalter (Princeton Professor of English, Emeritus) discussed the chapter on Augustine and how her house is a micro-museum. That seems somehow connected to your use of icons.

JSF: Visuals can become like exhibits in a book because the whole point of an exhibit is to take something out of context and say, “Let’s look at it, just on its own — let’s put it in a case and take something that we might ordinarily overlook, and see what’s special about it.” In a book you just can’t help but have that be the case anytime you have something that isn’t a word. The problem is that everyone’s so inclined to think that anything you do that isn’t straight ahead is a gimmick. It’s a kind of thinking that is completely absent from the way people talk about visual art or music. What would a gimmick sound like in pop music?

NLR: Still on the subject of visuals in the book, can we talk about the ellipses? You fill a couple consecutive pages with them in the novel. If Everything Is Illuminated goes on to be published in several editions, is it more important to you to have the exact number of lines of ellipses or that it finish the page?

JSF: I don’t care how many there are. It’s not numerology or anything like that. I do like how it ends the page. Like the “we are writing” thing — I like the way it looks. I’d do another page of it. Originally I had a lot more ellipses — I think I had three full pages, but my editor thought that would be distracting, and I think he was probably right about that. I did enough “we are writing”s to fill a page. There’s a fine line. There’s a point to which the more you do the more powerful the effect, and then at a certain point you just become an idiot.

NLR: Do you feel like there’s a pressure on young writers to be spokesmodels for their writing? The jackets of books by young writers often feature photos that could appear in a modeling or acting portfolio. They are presented as part of the book — obviously the author is part of the book — but like the author’s physical appearance is somehow part of it.

JSF: I’m always curious about what an author looks like. I guess I wish I weren’t, and of course I know in my heart that it doesn’t matter at all. I think it’s not a bad curiosity — I don’t need authors of the books I love to be good-looking. I just want to feel a connection with them. I do think the culture now has taken it a little bit further — a little bit too far. Books have become about the story about the book rather than the story within the book.

NLR: These days you could pick up an issue of Vanity Fair and instead of it featuring “18 Performers Under 18” it could be all of the young New York writers standing around, looking very … writerly.

JSF: In a way that’s bad, but in a way it’s very good. Look, not enough people read in our culture. There’s an anxiety about reading. Can you imagine if you saw a billboard for a book? If I had a billboard for my book, people would say, “What a sellout, what a commercial jerk.” On one hand, I would say that, too. I understand the anger over the commodification of literature. On the other hand, if you accept that you want people to read a lot of books — to read books like they listen to music, and go to museums — then maybe books should respond to the culture in the same way that other media have. Nobody sneers at advertisements for shows at the Whitney. I think it would be better if people were reading Paul Muldoon’s poems than listening to Britney Spears, so how can I accept that Britney Spears is plastered everywhere and yet Paul Muldoon is kept on a tiny cover?

NLR: What are the books you love, out of curiosity?

JSF: Well, the classics are classics. Kafka. Bruno Schulz. I really liked W.G. Sebald, who died a few years ago. There’s a writer, Helen DeWitt, who wrote a book, The Last Samurai, not to be confused with the movie that’s now in theaters. It’s an amazing novel. David Grossman is wonderful. Aleksandar Hemon.

NLR: It seems you were influenced by a lot of Marquez and Borges.

JSF: I think I was. I don’t think I am as much anymore. They are very impressive; I was impressionable. I bet you there are many, many people who decided to become writers when they read those two writers’ work. Now, do I still like that kind of writing? I have a hard time when I reread it.

NLR: What excites you about your new book (Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close)?

JSF: It’s hard. I feel like I’m constantly putting this carrot out of my reach. That’s the whole point: I’m doing something that’s harder than I can do. So I’m constantly setting myself up for — not disappointment — but reality. I feel like I’m always pushing up against myself, which is really exciting but is also a terrible way to work. I like what I’m working on, I guess; I like working on it.

NLR: How do you go about the process of writing?

JSF: For my new book, I have two files on my computer. One of them is the latest draft of what I’m working on. I’m now on the 34th distinct draft, which is about 400 pages. Then I have a file called “Castoffs,” in which I put everything that wasn’t good enough to be in the book but that I still might want later. It’s about 1,700 pages. It’s a pretty volatile process. And I never know what I’m doing. That’s the difference between art and craft, I think: the artist doesn’t know how things will end up. Joseph Brodsky used to say, “The rhyme is smarter than the poet.” If you put yourself in the way of having to find a word that rhymes with “leaf,” you’ll probably be led to a place more interesting than where you would have chosen to go. I assume that’s why Paul Muldoon writes the way he does — in his intricate, insane structures. It’s not only because they’re pretty and they sound great, but they make him do things he wouldn’t have done otherwise. They force fortunate accidents.

NLR: Can you talk a little bit about what you think your role as a writer is right now, how you’re contributing right now?

JSF: The function of some writing — most writing, almost all writing — is really just to entertain. I suppose that’s fine, although there’s no burden for writing to entertain: there’s so much TV, movies, and music. But there are still things that writing can do that other forms of expression can’t. Writing can move people in certain ways, it can startle or fascinate them in certain ways, it can call upon a reader’s imagination, force participation. I don’t know what I think my writing’s role in the world is, but it’s important to me to be original, to do things for the first time. And in a way that can be enough — it’s interesting just in the context of art to do something new. But I think once something new happens, once you learn how to see something differently in a painting, a book, or a song, you see things differently in the world, and people always need to see things differently in the world.

NLR: When you toured to promote Everything Is Illuminated, you began a project that involved people sending you things. Can you tell us about that?

JSF: Yeah, it was fun. When I went on book tour I gave everybody a plastic baggy. Inside was a little envelope that had my return address on it. And in the envelope was a 4x6-inch index card. It was blank, but at the bottom it said “self-portrait of _____” to let the recipient do whatever he or she wanted to do on it and send it back to me. I liked the idea, because something felt really off about going to places and doing readings and not having any avenue for people to respond. That had nothing to do with the way that I think about writing. So I handed out lots and lots and lots of these.

NLR: And did you get back interesting stuff?

JSF: Oh, it was incredible. Amazing stuff. People got really personal — expressing whatever was going on in their lives, just trying to express who they were. I thought at one point of putting them together and making a little book out of them, but once I got them I realized that I couldn’t — I can’t even show them to my friends. They’re too personal. It would really be a betrayal.

NLR: You didn’t think they would be that personal?

JSF: I guess I didn’t know. I didn’t know what people would say. I don’t know what I would do.

NLR: Do you want an index card?

JSF: I think my books are just lots of bound index cards.