A Paradox of Grand Designs: Thomas Jefferson and his Empire for Liberty

by Harrison Blackman ‘17

Wading through his idealism and hypocrisy, Harrison Blackman tracks the legacy of Thomas Jefferson.

“The University of Virginia is a remarkable combination of classical ideals and pure, American, do-it-yourself amateurism.”¹

— Robert A. M. Stern, Yale Dean of Architecture

“Nothing is unchangeable but the inherent and unalienable rights of man.”[ref]Hoftstadter, Richard. “Thomas Jefferson: The Aristocrat as Democrat.” The

American Political Tradtion: And the Men Who Made It. By Richard

Hofstadter. 4th ed. New York: Vintage, 1989. 23–56. Print.[/ref]

— Thomas Jefferson

“I fear the poor Negroes fare hard.”[ref]Jackson, Lawrence P. “Pictures from a Peculiar Institution: Writing American

Slavery: Lawrence P. Jackson on River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in

the Cotton Kingdom and Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His

Slaves.” LA Review of Books 30 May 2013: n. pag. Web. 8 Dec. 2013.[/ref]

-Thomas Jefferson

***

I’m in Charlottesville, Virginia, but I’m not visiting Monticello. I’m standing inside James Monroe’s house, Ash-Lawn Highland. Through the window and past a few hills and trees, I can see the outline of Thomas Jefferson’s famous home. You probably know the image; the neoclassical villa has been memorialized on the back of the nickel. I can tell you right now, it’s not as impressive in real life.

“James Monroe was a very modest man,” the docent explains, himself a particularly voluminous person, leading my family and another through the small, colonial, and haphazardly planned house. It is about eighty-five degrees Fahrenheit, and the docent is sweating, perspiration showing through his collared shirt.

“Before he died, he sold this house to pay off his debts so his children wouldn’t have a burden when they grew up,” he said. I smiled weakly. Monroe, after all, was still a slave-owner.

As we entered another cramped room, adorned with antique and uncomfortable-looking furniture, I pointed out a portrait of Thomas Jefferson.

“How’d he come by that?” I asked.

“Mr. Jefferson gave it to Mr. Monroe for his birthday,” the docent said, smiling, wiping sweat from his forehead.

I laughed. How would you feel, if on your birthday, your neighbor gave you a commissioned portrait of himself?

***

Ash-Lawn Highland is owned and operated by the College of William & Mary, which has an intimate and storied history with Mr. Jefferson.

Jefferson graduated from William & Mary in 1762, having completed his studies in only three years.[ref]”Thomas Jefferson.” Biography.com. A & E Television Networks, LLC, 2013. Web. 6

Dec. 2013.[/ref] He was dismayed that his classmates spent most of their time gambling and pursuing women, so after graduation he embarked on a rigorous five-year study of law, eventually becoming one of the most successful lawyers in Virginia.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] But Jefferson’s relationship with William & Mary would not end there.

Though he’s mostly known for the design of his own house, Monticello, Jefferson designed an expansion of William & Mary’s Wren Building in 1771.[ref]Turner, Paul V. Campus: An American Planning Tradition. New York: Architectural

History Foundation/MIT, 1990. Princeton University Library eReserve. Web. 6

Dec. 2013.[/ref] Because of the Revolution’s arrival in 1776, the project was never completed.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] For a while, Jefferson moved onto bigger endeavors, like writing the Declaration of Independence, serving as Minister to France, and becoming President of the United States.

Later in life, Jefferson’s dissatisfaction with William & Mary inspired him to start his own institution. He sought to create a “new kind of university, one dedicated to educating leaders in practical affairs.”[ref]”Short History of the University of Virginia.” University of Virginia. Rectors

and Visitors of the University of Virginia, 3 Aug. 2010. Web. 6 Dec. 2013.[/ref]

Tours are not always the most reliable sources of information, especially the ones held for college admissions. However, the fact that certain rumors or anecdotes are passed down might signal lingering bitter aftertastes that reflect historical personalities, including Jefferson’s own. Interestingly enough, the College of William & Mary still conveys bitterness towards Thomas Jefferson.

Visiting William & Mary for a college tour, I follow my student guide, a young African-American woman, who stops in front of a statue of Thomas Jefferson. Our third president is standing astride, left arm on his hip, his eyes looking to the right, up and away.

“Do you know who this is?” she asks, as all tour guides do when they are presenting something obvious.

“Thomas Jefferson,” someone’s dad says.

“That’s right,” she says. “Now, we all know that Jefferson was always short on money, so when he started the University of Virginia, he came to his alma mater, William & Mary, for assistance. William & Mary gave him seventeen thousand dollars to start UVA, which was a lot of money back then.”

She smiles. “Well, Jefferson died shortly thereafter, and neither he nor the University paid William & Mary back, which caused William & Mary some financial problems down the line.”

I hold my breath, suddenly very interested.

“So, in 1992, William & Mary asked UVA for the money back — they’re both public universities in Virginia, and the college didn’t even ask for the money adjusted for inflation.” She shrugs. “The University of Virginia gave us a statue of Thomas Jefferson.”

There are a few chuckles in the group, and I find myself laughing.

“UVA asked William & Mary to orient the statue so that he would face west, towards Charlottesville. Well, William & Mary was going to have none of that. The physics majors placed him here, so that he is looking through the window of the girls’ bathroom.”

Now everyone is laughing.

“So we call him Peeping Tom,” she says.

And the crowd goes wild.

***

Sometimes I cannot believe the egotism of Thomas Jefferson. Stories where he gives portraits of himself to neighbors are echoed in modern accounts of his institutional successors, who, rather than owning up to their obligations, donate statues of their founder to rectify past debts. What kind of man could have spawned such bitter anecdotes, such institutionalized arrogance, yet also be bestowed with immortality as a champion of democracy?

I treasure every legend of Jefferson’s hubris I come across. Every time I hear about Jefferson’s flaws, I find solace in the fact that he was not a god, but a human being, just like the rest of us. But was Jefferson really like the rest of us? It seems he might have been both more deeply flawed and more radically talented than the average person.

In terms of talent, he was brilliant. Despite lofty political ideals he floated around in private correspondence, he was firmly devoted to the practical arts. He wrote an encyclopedic work of his state’s history, invented a new hempbeater, developed a new moldboard plow, maintained daily barometric readings, and conceived the American decimal system of coinage.[ref]Hoftstadter, Richard. “Thomas Jefferson: The Aristocrat as Democrat.” The American Political Tradtion: And the Men Who Made It. By Richard

Hofstadter. 4th ed. New York: Vintage, 1989. 23–56. Print.[/ref]

On the other hand, Jefferson’s ideals and his inconsistent practice of them gives us a fuller insight into his paradoxical character. Jefferson “never wrote a consistent political theory — because he had no system.”[ref]Ibid.[/ref] Jefferson’s political philosophy was incoherent, dependent on the political conditions (and the realities) that surrounded him. As a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he strongly opposed Federalism and believed in “a nation of small farmers,” in which manufacturers and urban elites would be kept to an absolute minimum in American society.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] He espoused “a wise and frugal government” that protected men from one another “but left them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement.”[ref]Jefferson, Thomas. “First Inaugural Address.” Presidential Inauguration 1801.

Senate Chamber, U.S. Capitol. 4 Mar. 1801. The Avalon Project. Yale Law

School, 2008. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.[/ref] Jefferson’s strong but conflicting ideals became even more incoherent when he assumed the presidency.

As President, he did little to destroy Alexander Hamilton’s established, Federalist system of economics. While he did allow the First National Bank’s charter to expire,[ref]Hoftstadter, Richard. “Thomas Jefferson: The Aristocrat as Democrat.” The

American Political Tradtion: And the Men Who Made It. By Richard

Hofstadter. 4th ed. New York: Vintage, 1989. 23–56. Print.[/ref] by purchasing the Louisiana Territory in 1803 he expanded the role of the Federal government, stretching the limits of presidential power allotted in the Constitution and disregarding his strict constructionist view of the document.[ref] Ushistory.org. “Westward Expansion: The Louisiana Purchase.” US History.

Independence Hall Association, 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.[/ref] Even though the Louisiana Purchase was intended to allow more space for a nation of small farmers, it undermined his Democratic-Republican political ideals. Regardless, the nation of all small farmers was not meant to be, and even he may have had a hand in that.

His tacit acceptance of mercantile interests came about because of his party’s lack of a plan for an agrarian society — and in effect, he adopted laissez-faire capitalism. Unaware that economic relationships involve an “inherent taint of exploitation,” he did not understand any need for government intervention.[ref]Hoftstadter, Richard. “Thomas Jefferson: The Aristocrat as Democrat.” The

American Political Tradtion: And the Men Who Made It. By Richard

Hofstadter. 4th ed. New York: Vintage, 1989. 23–56. Print.[/ref] This is considerably ironic when one considers the contrast of his attitude toward farmers and his attitude toward his slaves — and that his laissez-faire philosophy ultimately led to the destruction of his ideal agrarian society.

By the time the Embargo Act of 1807 decimated the mercantile shipping industry in the Northeast, which depended on trade with England, Jefferson endorsed domestic industry, if only to be self-sufficient,[ref]Ibid.[/ref] but his decision left weighty consequences on the country as a whole. Facing war with Britain, James Madison, his successor of the same party, established the Second National Bank and followed more stringent Federalist policies than the Federalists themselves, raising tariffs and protections on domestic industries.[ref]Hoftstadter, Richard. “Thomas Jefferson: The Aristocrat as Democrat.” The

American Political Tradtion: And the Men Who Made It. By Richard

Hofstadter. 4th ed. New York: Vintage, 1989. 23–56. Print.[/ref] Thus, Jefferson’s inconsistent politics betrayed his agrarian society, and the United States would never be the same again.

***

Flash forward to the present day, and we can see that Jefferson’s agrarian society failed to materialize. But Jefferson’s conflicting ideals live on, not through an economic system, but through another institution whose legacy is also founded on paradox and derivative ideas. By analyzing Jefferson’s ambition and architectural design of the University of Virginia, we can further assess his character and the modern perception of the founding father.

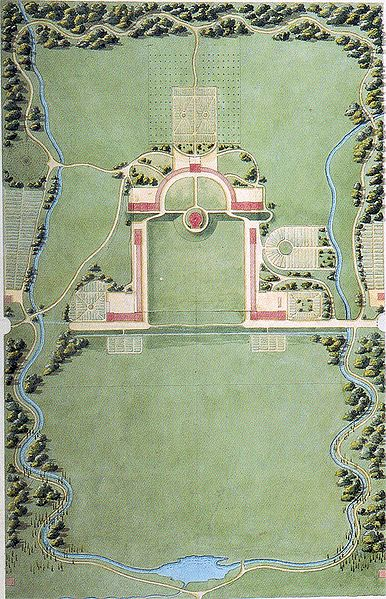

When Thomas Jefferson set about starting the University of Virginia, he envisioned an academical village: pretentious vocabulary aside, he wanted a college to be a community in itself, a “city in microcosm,” because in his estimation, William & Mary had become corrupted by neighboring Williamsburg.[ref]Turner, Paul V. Campus: An American Planning Tradition. New York: Architectural

History Foundation/MIT, 1990. Princeton University Library eReserve. Web. 6

Dec. 2013.[/ref]

UVA is most known for its “revolutionary” design, an innovative layout of buildings which succeeds in producing what urban planner Kevin Lynch calls imageability: “the quality in a physical object which gives it a high probability of evoking a strong image in any given observer.”[ref]Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. 20th ed. Cambridge: MIT, 1990. Princeton

University Library eReserves. Web. 6 Dec. 2013.[/ref] For Jefferson, UVA’s central campus is successful because it combined elements of campus design that are now closely associated with the design of the prototypical American college — when people hear the word college or university, they usually picture something that looks like UVA.

The University of Virginia is formed around a long quad or mall, a loose derivative of the Collegiate Gothic quadrangle present in British colleges like Oxford, Cambridge, and perhaps best emulated in the United States at Yale and Princeton. At these colleges, gothic quadrangles are surrounded by four walls, meant to recall the image of a monastery’s cloister, harkening back to many of the British and colonial colleges’ religious roots.

But Jefferson sought to create a school that would enrich knowledge in the arts and sciences, and so at the end of his quadrangle, he placed a neoclassical library, known as the Rotunda, reflecting his modern and secular view regarding the nature of education.[ref]Stern, Robert A. M., host. “The Campus: A Place Apart.” Dir. Murray Grigor.

Perf. Charles Jenks et al. Pride of Place: Building the American Dream.

Prod. Malone Gill Productions. 1986. Princeton Video Reserves. Web. 8 Dec.

2013.[/ref] With the dimensions designed to be half the height and width of the Roman Pantheon, the Rotunda is clearly Jefferson’s conscious effort to manifest his vision with ancient Republican stability.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] Colonnaded arcades connect more Greco-Roman styled buildings, which form a three-faced quad. It is in these adjoining buildings that Jefferson intended instructors and students to live side by side, forming an academic community that would best evoke the monastery’s cloister.[ref]Turner, Paul V. Campus: An American Planning Tradition. New York: Architectural

History Foundation/MIT, 1990. Princeton University Library eReserve. Web. 6

Dec. 2013.[/ref] Like many of Jefferson’s other ideas, this arrangement did not last. Soon after UVA’s opening, the professors moved out of the academical village at the behest of their wives, who couldn’t stand living amongst the students.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] As it was for his governmental designs, here practicality outweighed idealism, betraying Jefferson’s predispositions — though his ideals were grand.

In UVA’s youth, Jefferson’s central quad extended into the distance, to the West, symbolic of America’s boundless potential for growth — just one of his architectural ideals that would fall short in practice.

As Princeton and Yale would add collegiate gothic buildings in the 1930s in order to “add a thousand years of history,” (so said Woodrow Wilson[ref]”The Origins of the Collegiate Gothic Style.” Princeton University. Trustees of

Princeton University, 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.[/ref]), so did Jefferson, if only in the form of the classical. According to architect Robert A. M. Stern, Jefferson added classical motifs to UVA so that he could “root the American experience in a past it never had,” inspiring students to go West and build a “New Rome in America,” an “Empire for Liberty” that would last for millennia.[ref] Stern, Robert A. M., host. “The Campus: A Place Apart.” Dir. Murray Grigor. Perf. Charles Jenks et al. Pride of Place: Building the American Dream.

Prod. Malone Gill Productions. 1986. Princeton Video Reserves. Web. 8 Dec.

2013.[/ref] While Jefferson’s ambition sounds hopelessly pompous, empire is something that the United States took from Jefferson’s words and never gave up. It is interesting to note that, like the Roman Republic he strove to emulate, Jefferson’s society was built by the labor of slaves. But even though the campus’ Doric columns were only made of wood, rather than marble, his building’s facades would resonate in the eyes of the American public, inspiring many campuses to come.

But is UVA correctly remembered as a revolutionary campus? Here, again, Jefferson’s myth fades.

UVA is not the first campus to possess these characteristics — rather, his design was a reformation and reimagining of various other campus plans. The word ‘campus’ comes from the Latin, meaning ‘field’ — first used to characterize the lawn in front of Princeton’s Nassau Hall, which in the colonial era was Princeton’s sole college building, housing students, professors, and classrooms.[ref] Beyer Blinder Belle Architects & Planners. Princeton Campus Plan: The Next Ten

Years and Beyond. Princeton: Princeton University, 2008. Print.[/ref] In fact, if not for Princeton, we’d probably be calling college campuses “Yards,” in the tradition of Harvard Yard.[ref]Ibid.[/ref]

William & Mary’s campus possessed an axial arrangement that was likely combined with Princeton’s quad when the original plans for the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill were drawn up. While not entirely realized in its long development, Chapel Hill’s campus plan called for a “grand avenue” separating two rows of buildings, forming a mall.[ref] Turner, Paul V. Campus: An American Planning Tradition. New York: Architectural

History Foundation/MIT, 1990. Princeton University Library eReserve. Web. 6

Dec. 2013.[/ref] The mall would become a relatively common motif of early American colleges.

South Carolina College, (now known as the University of South Carolina), had an architectural contest in 1801 for the design of their campus.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] The winner was Robert Mills — curiously, one of Thomas Jefferson’s architectural assistants.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] Mills planned for a central building with two long wings that formed a three-faced quad; unfortunately for his design, the trustees changed their mind and arranged their buildings in a “horseshoe” arrangement, which was effectively a mall. South Carolina College became the first campus to fully realize this design.[ref]Ibid.[/ref][ref]Colonial architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe is also another great example of one of Jefferson’s forebears. Having renovated Princeton’s Nassau Hall and worked on various college architectural projects, the majority of his designs featured domed central buildings and wings that formed three-sided quadrangles. (Turner, Paul V. Campus: An American Planning Tradition. New York: Architectural History Foundation/MIT, 1990. Princeton University Library eReserve. Web. 6 Dec. 2013.)[/ref]

Another of Jefferson’s influences came from Joseph-Jacques Ramée, who designed Union College in New York. Featuring a central building with two wings connected by colonnaded arcades, this arrangement forms a mall axis, and is the closest in spirit to Jefferson’s design at UVA.[ref[Ibid.[/ref]

Jefferson’s plan for UVA was so similar to Union College that it prompted one historian to suggest that Jefferson borrowed Ramée’s plans for Union College and never returned them, explaining their absence from Union’s library.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] While there is no evidence of this being the truth, it is fascinating that such a rumor could exist, considering Jefferson’s high regard in the annals of American history. It suggests a complex man whose reputation for honesty and higher learning may have not been so stellar not only among select historians, but also among his peers — leaving behind a bitter aftertaste.

So, is UVA the original quintessential American college campus? Clearly not — but over time, people began to think it was.

***

Despite UVA’s appeal as a feat of architecture today, the university’s design had remarkably little influence on other college campuses until 1893, when the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago popularized Beaux-Arts principles and ignited the City Beautiful movement.[ref]Turner, Paul V. Campus: An American Planning Tradition. New York: Architectural

History Foundation/MIT, 1990. Princeton University Library eReserve. Web. 6

Dec. 2013.[/ref] The fair held up Thomas Jefferson’s UVA as a prime example of French and Roman-influenced American architecture, eventually inspiring the Beaux-Arts architectural firm McKim, Meade, & White, who designed Columbia University’s current Morningside campus in 1897.[ref]”A Brief History of Columbia.” Columbia University in the City of New York.

Columbia University, 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.[/ref] In 1898, Stanford White of the aforementioned firm even renovated UVA’s rotunda after a fire, transforming the building into the Beaux-Arts style.[ref]”History of the Rotunda.” University of Virginia. Rectors and Visitors of the

University of Virginia, 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.[/ref] Though the Rotunda was restored in 1975 to Jefferson’s original plan,[ref]Ibid.[/ref] the fact that the supposed catalyst for a new building style was remade into the image of the new building style suggests that it was not the true inspiration for the City Beautiful movement in the first place. History’s revisions made it seem Jefferson had foreseen the future, even when he had merely acknowledged and built on the past.

Nonetheless, even though the University of Virginia borrowed many elements from previous campus plans and had little influence on the design of the majority of campuses constructed in the 19th century, since the 1890s UVA has been deified as the quintessential prototype of the American college experience. Why? Well, Thomas Jefferson was until recently unquestioned as one of our noblest founding fathers, his likeness featured on the nickel, the two-dollar bill, and a grandiose memorial in Washington, D.C. History has a habit of placing certain people on pedestals, and Jefferson’s enthusiasm for grand ideas made him an attractive candidate for immortality in the eyes of generations of scholars.

Today, the University of Virginia is far from Jefferson’s perfect, academical village. The Rotunda, once used as a library, mainly serves the purpose of a tourist attraction, dedicated in 1987 as a World Heritage site by the United Nations.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] Only honors students are given the privilege of living in Jefferson’s ancient student dormitories on the quad,[ref]Stern, Robert A. M., host. “The Campus: A Place Apart.” Dir. Murray Grigor.Perf. Charles Jenks et al. Pride of Place: Building the American Dream. Prod. Malone Gill Productions. 1986. Princeton Video Reserves. Web. 8 Dec. 2013.[/ref] another practical reason to betray Jefferson’s vision, as UVA limits the sharing of the academical village with a select few.

When one considers the current physical design of the campus, it is easy to conceive that Jefferson would have felt insulted. The central quad is no longer open to the West, symbolizing how the blank edges of America’s map have been filled in, as America’s so-called “Manifest Destiny” has been fulfilled. But being an “Empire for Liberty” has had its costs — as the University has grown, a hodge-podge of incoherently placed buildings has come at the cost of Jefferson’s vision. Like America itself, suburban sprawl has overtaken a pastoral landscape, the academical village a mere monument to history in a sea of commercialized development, which would have sickened Jefferson, since he considered cities to be pestilent and corrupting places.[ref]Hoftstadter, Richard. “Thomas Jefferson: The Aristocrat as Democrat.” The

American Political Tradtion: And the Men Who Made It. By Richard

Hofstadter. 4th ed. New York: Vintage, 1989. 23–56. Print.[/ref]

In the summer of 2013, a University of Virginia committee proposed that UVA should cease being a public institution and become a private university.[ref]Vedder, Richard. “Is the University of Virginia Going Private?” Minding the

Campus: Reforming Our Universities. Manhattan Institute, 12 Sept. 2013.

Web. 11 Dec. 2013.[/ref] From the surface, it would seem that UVA aims to become an Ivy League-like institution similar to the University of Pennsylvania, in part because then it wouldn’t have to accept Virginia students with lower test scores, whom UVA is required to admit because of their status as a public state university. If they went private and cut out this faction, (which also requires the most financial aid expenditures), then their U.S. News and World Report Ranking would probably rise.

If UVA goes forward with this plan, it might seem that they will have completely betrayed Jefferson’s lofty vision as a place of learning for all Virginians. But I disagree — this elitist status was implicit in UVA’s founding from the beginning, descendant from Thomas Jefferson’s aristocratic worldview. While he gushed over the ‘inherent wisdom’ of small farmers, his low opinion of Europe’s peasants[ref]Hoftstadter, Richard. “Thomas Jefferson: The Aristocrat as Democrat.” The

American Political Tradtion: And the Men Who Made It. By Richard

Hofstadter. 4th ed. New York: Vintage, 1989. 23–56. Print.[/ref] and his slaves confirms that this is an echo of his character, a bitter aftertaste.

Just as practical issues of money brought down Jefferson’s estate at his death, so does the practical issue of money influence UVA’s plan of action. Just as Jefferson shirked his obligations to his friends, his alma mater, and his slaves, UVA would betray the people of the state they were founded to educate in order to improve their ranking in a magazine.

***

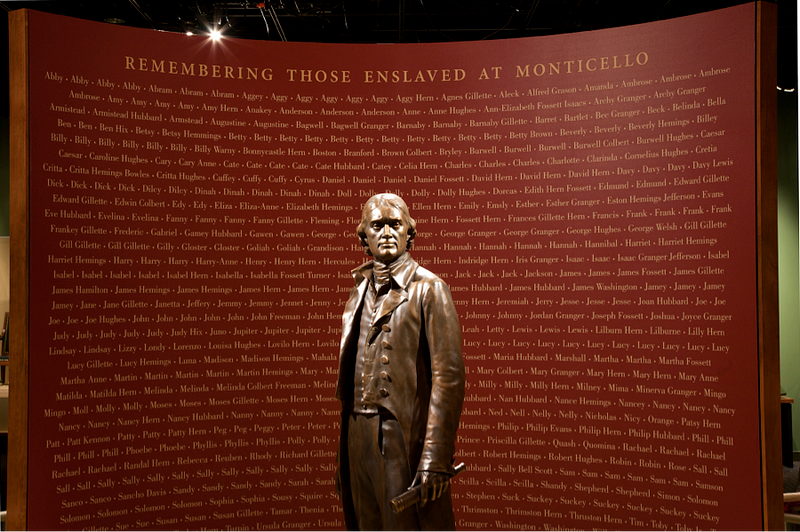

UVA’s current ambition to become a private university is troubling, and should be duly noted as a flash point for the debate considering Jefferson’s legacy. But no analysis of Thomas Jefferson would be complete without an investigation of his status as a slave-owner, a status that, unsurprisingly, contrasts considerably with his view on free white farmers. Jefferson believed that “those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God,” and thus were immune to corruption.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] If he was speaking of farmers, then he obviously was forgetting his slaves, who tilled his land but were definitely treated as less than “God’s chosen.”

(Maryland Historical Society).

Jefferson’s ideal views on human liberty are regarded as some of his greatest achievements, though the ideas that “all men are created equal,” and are endowed with the rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” are but an eloquent rephrasing of John Locke’s concept of natural rights. Of course, when he said “men,” it’s fair to say that Jefferson meant white, landed men, excluding blacks, women, and property-less white men.

Though Jefferson did draft a law for gradual emancipation, he never introduced it, instead only advancing his proposals to friends in private correspondence.[ref]Hoftstadter, Richard. “Thomas Jefferson: The Aristocrat as Democrat.” The

American Political Tradtion: And the Men Who Made It. By Richard

Hofstadter. 4th ed. New York: Vintage, 1989. 23–56. Print.[/ref] Far from being revolutionary, Jefferson believed that slavery would be solved eventually, and according to the traditional interpretation, political pragmatism stayed his hand. However, when one considers how he actually treated his slaves, it seems that Jefferson wrote his non-slavery bill on a lark, placed it in a desk drawer and forgot about it.

In a similar context to this suggestion, the historian Richard Hofstadter noted “the leisure that made possible his great writings on human liberty was made possible by the labors of three generations of slaves.”[ref]Ibid.[/ref]

The paradox of this situation is astounding. History’s image of Thomas Jefferson as the “benevolent slavemaster,”[ref]Ibid.[/ref] is simply false. Jefferson actively committed crimes against the men, women, and children he held in bondage. Children were beaten and overworked.[ref]Jackson, Lawrence P. “Pictures from a Peculiar Institution: Writing American

Slavery: Lawrence P. Jackson on River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in

the Cotton Kingdom and Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His

Slaves.” LA Review of Books 30 May 2013: n. pag. Web. 8 Dec. 2013.[/ref] The recently exhumed skeletons of enslaved children reveal startling abuse; their vertebrae were fused together from the hard labor — not to mention the fact that they died as children is damning.[ref]Ibid.[/ref]

Not only did Jefferson commit heinous crimes against his slaves, but he also took advantage of them to his grave, mortgaging their “value” to finance the construction of Monticello.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] At his death, he was embroiled in so much debt, he couldn’t even hold his promises to the free people he knew, and “he barely freed his own sons and daughters with [the slave] Sally Hemings, who herself was not freed.”[ref]Ibid.[/ref] Of his six hundred-plus slaves, he only freed nine of them.[ref]AP. “SURPRISE! Jefferson Only Freed Nine of His 600 Slaves.” Ebony 26 Jan. 2012: n. pag. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.[/ref]

In Lawrence P. Jackson’s LA Review of Books essay on Henry Wiencek’s Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves, the Emory professor makes the following analysis of Jefferson’s commodification of his enslaved laborers:

“As a farmer [Jefferson] would also school his associates that it was ‘not their labor but their increase which is the first consideration with us,’ which is to say that Jefferson farmed people. In this way Jefferson reduced his discussion of universal liberty to prattle, and consigned the descendants of men like John Hemings — a man who had the same father as Jefferson’s wife — to slavery in perpetuity.”

***

Thomas Jefferson was a champion for liberty, the founder of UVA, the author of the Declaration of Independence — and simultaneously considered his slaves agricultural commodities. He was, and still lives on as, a paradox of grand designs.

What can we make of Thomas Jefferson? How do we understand a man so talented, but so flawed?

A human paradox, Jefferson was arrogant and pretentious, but inadvertently helped lay the foundation for much of the United States’ ideals through the Declaration of Independence and reformulated previous architectural plans to influence the college experiences of countless Americans. He supported freedom, but held and abused men, women, and children in bondage. His successors in the presidency as well as the University of Virginia betrayed his vision of agrarian utopia, but in the end, manifested his Empire for Liberty.

Thomas Jefferson was a brilliant, ugly person. Like Jefferson’s life, American history is filled with many triumphs and many atrocities. We celebrate our individualism, our cultural pluralism, and our civil rights — but there is also the past genocide of American Indians, the former enslavement of African-Americans, discrimination in all shapes and forms, and pending environmental catastrophes. Contradictions exist, but to truly understand our heritage, we must absorb all the facts, decipher for ourselves what can be considered true and false. What remains may be a bitter aftertaste, but how else can we try to overcome these evils, if not by knowing the contradictions that made the world as it is today?

[1] Stern, Robert A. M., host. “The Campus: A Place Apart.” Dir. Murray Grigor. Perf. Charles Jenks et al. Pride of Place: Building the American Dream.

Prod. Malone Gill Productions. 1986. Princeton Video Reserves. Web. 8 Dec.

2013.