What We’re Loving — April 2014

Images courtesy of kinokoteikoku.com, Wikimedia, and Penguin.com.

A friend sent me a song the other day. It’s called FLOWER GIRL, in all caps. The song is by a band called Kinoko Teikoku — “Mushroom Empire” in English. The album cover features a pattern of small daisies set against a dusky blue backdrop. “Listen to this Japanese shoegaze song”, said my friend’s message. I pressed play, pretending that I had an idea of what Japanese shoegaze was but really not knowing what the hell to expect. The song put me in a state that I can only describe as trancelike. Walls of static-y instrumentals are placed on top of each other in intervals while a female singer’s voice dances on top of the layers. Drums and a strumming guitar keep a steady beat as the song evolves in minute increments. Listening to the song makes me think that a bunch of fuzzy critters are swimming through my head. At one point, all the instruments and percussive elements that have built up throughout the song cut out except for the single female vocalist. Then the bass comes in and the song grows again, going further than before. The effect is akin to a beat drop. I listen to this song whenever I feel myself getting anxious and it does wonders. If you enjoy FLOWER GIRL, check out Japanese shoegaze artists Pastel Blue and Tatuki Sekusu.

— Emily Tu

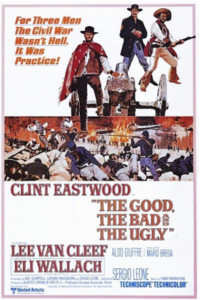

At first I was just looking for some movie music that was Western-themed. I was writing a cowboy-esque short story, and I needed some inspiration. Cruising Spotify, I found Ennio Morricone’s soundtrack for The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly — and my world was changed.

Okay, maybe that’s melodramatic, but Morricone’s soundtrack is incredible — it redefined the Western film score. You probably already know The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly’s theme song — that whistle! — but there’s a lot more to like here. The best tracks include the haunting “Il Deserto,” the feverish “L’Estasi Dell’orro” and the climactic “Il Triello,” but the whole soundtrack is amazing. It’s funny — most of the songs consist of a catchy theme, an interlude, and then a repetition of the theme. You don’t notice that the repetition is nearly the same, but the theme’s that good you don’t care.

Watch the movie too. Sergio Leone’s Italian Westerns are epic. And Clint Eastwood’s stoic bounty hunter, “The Man With No Name” is an archetype borrowed from the Japanese Samurai movie Yojimbo, lifted from Dashiell Hammett’s unnamed private detective in the novel Red Harvest. You can’t get more pop-culture literary than that.

— Harrison Blackman

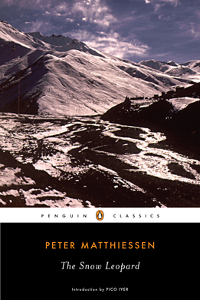

Peter Matthiessen’s contributions to the modern literary experience cannot be overstated. In addition to co-founding The Paris Review, he was notable for his non-fiction writing on nature, travel, history, and spirituality. If that weren’t enough, he also found a way to extend himself into the world of fiction (one of his novels, Shadow Country, received the 2008 National Book Award). In light of his recent passing, I decided to start reading Matthiessen’sThe Snow Leopard (which itself won two National Book Awards). But really I suspect that this talk of prestige would be of little interest to the author. In The Snow Leopard, Matthiessen recounts his 1973 journey in the Himalayas with biologist George Schaller (identified as GS throughout the book) to find the elusive bharal — the Himalayan blue sheep — and perhaps also one of its predators, the snow leopard that has rarely been documented by man. They are accompanied by native porters and Buddhist herders, including the enigmatic man named Tukten, who throughout the voyage seems to be a perverse shadow of Matthiessen’s essential self — the regrettably human self, which has found no solace from rage, loneliness, and death.

This note of death, while it does not overwhelm, certainly resounds in Matthiessen’s tale: an old man ushered by four men to a temple, which is to be his final resting grounds; great, near-rabid mastiffs whose jowls seethe with the promise of mortal taste; the author himself, who frequently acknowledges Death’s failed advances in the oft-dangerous mountainscape. But Matthiessen, I believe, wishes us to think differently of the pale horse rider. Death kneels to the one who understands that the world is experienced at once, and our only concern should be the present. Matthiessen does not coerce us, though. We are to light our own candles in the dark, and by doing so we might be able to enjoy what has been set before us. The sounds of Matthiessen’s young “sun” playing, or the beautiful expression of a little girl who cups her hands with the blood of a slaughtered animal because she must. I am taking my time with Matthiessen’s journey because that is what it seems to ask for. I try not to think about what I have read, or what book is next in my queue. This is the one that is in my hands, and I suppose that is the only thing that matters.

— Aaron Robertson