What We’re Loving — Summer 2015

Sons and Lovers (1913) is my first dance with D.H. Lawrence. The novel is a favorite of one of my old high school teachers, who gave it to me as a gift. The story follows the Morels, a poor English family of four siblings and two bickering parents, and particularly the lives of brothers William and Paul. It is a tale of suppressed and deflected desires that also recalls the plight of Oedipus. But Lawrence’s novel is challenging for different reasons. I am in the latter half, whose sections focus on Paul Morel and his frustrated relationships with three women: the longsuffering Miriam, stony Clara, and his fretful mother Gertrude. Paul loves (and hates) them all for different reasons and struggles to devote himself fully to any of them. It’s somewhat comforting to dive into a book of mercurial emotions. The characters do not behave inconsistently, but their feelings fluctuate violently between tenderness and spite towards themselves and one another. When a character is so bold as to actually make a decision, I tend to let out a wee joyful shout. Lawrence’s prose is neither showy nor dense, but his descriptions of English landscapes and the way in which people interact with them are lovely and significant for a reason I have not yet parsed. Sons and Lovers is exactly that earnest psychological novel that I needed in this moment: a domestic drama that offers refreshment from some of my other summer reading (filled as it were with death and violence).

–Aaron Robertson

Carolyn Kizer was a poet unafraid of adjective or of Adam. Her Mermaids in the Basement: Poems for Women mourns and burns for the tragedies of women: women used, women unloved, and women unwritten, from the classical to the contemporary. Streaming commas sweep along with the ease of a Woolfian sentence, flowing through scalding accusation and unexpected figure with a grace that makes the reader sit tight, admire the view, and reserve judgment for another time. I’m loving Kizer’s work for its weird collision of rage, bitterness, wistfulness, and intimacy, although suspicious about the way it occasionally reads like a manifesto. Kizer relies on a universal “we” and “our” to speak in the voice of womankind. Who is this “we”? Is it possible to unite the diversities and fluidities of feminine experience into some monolithic “we” voice? Who gets excluded when “we” try to do that?

–Ayelet Wenger

I visited the National Gallery of Denmark when I was in Copenhagen this summer and, for someone who often goes to art museums more out of a sense of intellectual obligation than authentic excitement, it was probably the most enjoyable and informative museum I’ve been to. Its permanent collection includes European art (mostly paintings) from the 14th century to present day. While their collection was certainly impressive, what I enjoyed most was the placards they provided — for certain paintings — explaining why exactly that painting, artist, or style was significant. The placard that made the biggest impression on me was an explanation of Peter Paul Rubens’s The Judgement of Solomon, which walked me through line, composition, color, and history in the painting in an engaging and insightful way. Besides its general European collection, the Gallery also offers a collection of Danish art from 1750 to 1900. It was extremely enlightening for me to see the threads of continuity within Danish art and to conceive of it as a tradition of its own. Although Copenhagen has many other stunning sights, I would definitely recommend the Gallery to art lovers and also those (like me!) who are still learning to love art.

–Whitney Sha

This July, Chris Gethard did a show for dogs. Before that, in 2011, Gethard began to host his own public-access television show on Manhattan Neighborhood Network. Gethard is a comedian who talks about depression and Morrissey, and the list of his show’s target demographics begins with “goons” and ends “people with severe depression, and jabronis.” This summer, The Chris Gethard Show moved from public-access to deep cable. On his Fusion debut, Gethard opened his monologue with “check it out, I have weird little claw hands.” He wore a white tee with “This is not important” sharpied on in all caps. Gethard wants his show to be weird, because regular, real people are weird. Intensely, Gethard wants his show to be real. In July, halfway through the episode for dogs, Gethard asked celebrity guest Jason Sudeikis, “Is this fun, or is this totally weird?” They stood on a floor of absorbent puppy pads, surrounded by thirty-one unleashed dogs. There was no human studio audience. In this monologue, Gethard had talked about breaking the species-barrier and becoming an even more inclusive television show. After that, Gethard let dogs in on some human secrets: “There’s a big difference between sleeping, and being put to sleep.” Sudeikis riffed, “Unless, of course, you’re Bill Cosby.” No one laughed, because mostly everyone was a dog. In response to Gethard’s “Is this just totally weird” question, Sudeikis said things were about fifty-fifty: “It sways to being really fun, and then it’ll just be weird, but then the weird’s fun — there’s nothing bad about this whatsoever. It’s soothing.” This is Gethard’s formula, and it works.

–Will Lathrop

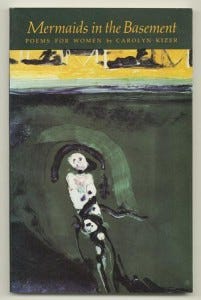

This summer, I read Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, and it was perhaps the deepest, saddest, and most emotionally complex book I’ve ever read. I can only do it a disservice here, but in the spirit of Woolf’s Britain, I might as well give it the old college (university?) try.

By my definition of a novel, Dalloway is its zenith. To me, novels can communicate something about humanity that nonfiction wouldn’t communicate properly. The general method is to create an immersive example with verisimilitude. In other words, by watching the plot of a novel play out in a believable way, the reader might find herself believing that the particular way that the events unfold exemplifies truths about how events unfold in the real world. Dalloway does this flawlessly, though it’s written like poetry. Woolf tackles the deepest problems of human existence. Hurtling past ahead-of-her-time insights on feminism, classism, imperialism, sexuality, mental illness, she dives into the most difficult to articulate yet universal problems of humanity. The limitlessly tragic inability of people to express themselves properly, especially when affection and pride compete. The fear of the future, which can mercilessly separate us from exactly what we desire. The sting of regret, which ceaselessly returns to haunt us with the unbearable longing to fix our past mistakes. The bittersweet consolation that, since all of us can experience a deep isolating alienation from others, we can come together with mutual understanding of it, if we are brave with our hearts. These fragments have little weight when stated so plainly, but when they are experienced through the struggles of the achingly real characters in Dalloway, the reader enters a state of mournful reflection. She thinks about the empathy, bravery, and focus that are required to live a life of goodness and love. It is almost like inhabiting, for a moment, Woolf’s extraordinary and unique mind. We could all benefit from a brief foray there: it is contemplative, brilliant, aware of the suffering of others, cynical, but ultimately hopeful, if only for the possibility of the earth-shattering, beautiful beyond comprehension, undying love that people can share for one another.

–Justin Poser

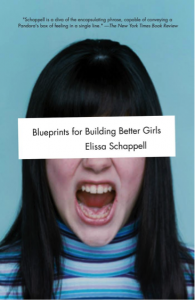

Elissa Schappell came to my high school during my senior year and did a reading from a book of hers, titled Blueprints for Building Better Girls. I was under the impression that the book was a novel, because she’d stopped reading at such a climactic moment — but it turns out that it was a collection of short stories, sometimes briefly connected through characters and their relationships. What greeted me was a cast of dysfunctional women, molded and expanded on from archetypes of women’s roles in 1970s America. Schappell writes in such a nonchalant and anger-provoking manner, creating absurd characters out of completely normal women. I repeatedly found myself a little too invested in her characters’ lives. Her metaphors were also a little unsettling — one that I still cannot get out of my head is when she compares sex to the repeated firing of a machine gun. This book made me angry, and I cannot for the life of me figure out why. Maybe it’s the endings that always seem unfinished, maybe it’s the audacity of her characters, or maybe it’s how she reveals the natural but sometimes shameful ambiguity that is instilled in many of us. After a whole academic year of reading required texts in class, it was refreshing to read something that elicited such a strong reaction from me.

Also, while I was reading this book on the elevator leaving work one day, an older lady tapped me and asked what I was reading. When I told her the title, she seemed surprised. I think she thought it was literally a book on appropriate etiquette for women because she asked me if it was “some kind of girls’ series”. I told her it was a book of short stories. She then smiled and said that it was great that I was reading, since “it’s so rare these days to see young people like you reading actual books!” and then offered to introduce me with a “nice young man working with us” who told her that he “appreciates women who read books”. This never happened.

–Megan Tung