Beggars for Good Soccer

by Angélica María Vielma ‘18

I have never been to England; I do not care for dreary weather or tea. I do care about Frank Lampard, Diego Costa, and Oscar. I have the utmost respect for manager José Mourinho. It is a good day when the sun is shining and Chelsea has qualified for the Champions League. Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa wrote that soccer presents “an opportunity for people to have fun…to feel certain intense emotions that daily routine rarely offers them.” Getting an excellent parking spot at the grocery store does not merit a grand cheer, just as discovering the fact that your favorite shirt has a tear in it does not merit foot stomping and groans. “Don’t mind me, I’m just upset that Chelsea lost today,” is something I have said to my friends and family more than once (Chelsea doesn’t have the best record in the league). Chelsea games merit foot stomping and cheering and shouting. Soccer elicits emotion usually reserved for momentous occasions in life. I cried when my brother graduated college and was commissioned into the Navy in May 2014, and I cried two months later, when Team USA lost to Belgium.

I do not know why I am a fan of Chelsea. I do not remember how I ended up choosing them over Liverpool or Man United or Barça. I do not remember when I learned the players’ names and numbers. Relationships in soccer are messy. No matter how many times your club, your team, lets you down, there’s an inexplicable magnetism that attracts you back each time. This emotional investment never ceases to amaze me. How many times has a bad loss or spectacular win dropped or raised the spirits of fans on an otherwise ordinary day? People emotionally and even financially invest in teams to which they may have no native connection. We proudly proclaim our citizenship in these imagined communities. Soccer appeals to us because it seems to escape any rationality. In fact, it is completely irrational to allow something so inconsequential to occupy such an important space in our lives. There is no logic in fanatically following a team. Max Weber said “The fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, by the disenchantment of the world.” Soccer makes it easier for us to imagine a community that empirically doesn’t exist. Soccer makes it easy for us to believe in magic; it escapes the logic of utilitarianism.

***

I have always loved sports. I grew up under the South Texan sun with five siblings. My two older brothers have always been my idols, and, if I wanted to spend time with them, I had to do what they wanted to do. Biking, skating, frisbee, baseball, football — my brothers were very active children, so I was very active too. Their favorite sport was football. My favorite sport was football. Sunday Night Football became just as much a part of our family as Sunday morning mass. That was the time I spent with my brothers. Eventually, they had to spend their Sunday nights doing homework; I kept watching games. My own passion became so great for football that in fifth grade, my mom signed me up to play in a youth recreational flag football league. I was the only girl on my team, The Longhorns, and we beat every other team in the league that season and took home tall gleaming, golden trophies. That was the only year I was allowed to play football; co-ed flag football was only for fifth graders and younger. However, I knew I had to play something. I had to run, had to jump, had to sprint. I had to keep feeling the blood pumping through my body and the hot sun on my face. Joining soccer was a spur of the moment thing. It was the only sport my school offered to girls. My only experience with soccer had been during short spurts of twenty-minute recesses, when my friends and I had played on a dirty lopsided hill because the big kids always claimed the green field. Now I was a big kid. Once again, I would be the only girl on my team. I was a girl in a boy’s world, familiar territory to me. However, it wasn’t the world of my brothers this time, or even of my classmates. This was my dad’s world.

My dad grew up in the house across the street from where we live now. He is the youngest of six siblings. My grandfather worked as a taxi driver before he was hired as the operator of the local bus station. My dad has worked with his dad for almost his entire life, beginning when he was nine. The only time my father did not work at the bus station, was when he attended boarding school in San Antonio. My grandfather committed himself to giving my dad and his brothers the opportunity to attend St. Anthony’s. My father took the chance. He was the goalkeeper for four years at St. Anthony’s but it took time before he was named to Varsity. On long walks or drives around town, I loved asking my dad to tell me stories of his high school, especially about his soccer team, the Mad Dogs. His summer nights at home were spent playing with twenty, thirty, and forty year old men on fields that had nothing but broken bottles and rocks. The goals did not have nets. My dad later attended The University of Texas Pan-American on a scholarship through the men’s soccer team for two years. To my dad, soccer and education are entwined. He sees soccer as the most important and beautiful game, and an essential part of anyone’s education. The sport teaches good character, dedication and commitment, a strong work ethic. Good character is the foundation of the Vielma household.

***

In the introduction to his book The Ball is Round: A Global History of Soccer, David Goldblatt speaks of the universality of soccer. It is the global game because of the ease with which it is played: you only need feet and a rag ball. There have certainly been instances in history where soccer has become complicated and has been manipulated by political forces, but it is equally true that soccer has been used by the opposite end of the spectrum, to consolidate nationhood and incorporate the working class into the idea of the nation. Soccer can represent an integrated community. People often try to see soccer as a reflection of society; we romantically compare the battles on the pitch to battles on actual fields. We place more value in games than what they’re worth. We make up these myths that are handed down for generations, and that is part of the appeal of soccer. It is something more than the sum of its physical parts. However in reality, soccer is not a reflection but a metonymy. It is a part of a whole, one that is instantly recognizable for a multitude of things. Soccer’s beautiful simplicity and metonymy attracts many.

I remember the day I asked my dad to join my middle school’s soccer team. The fee was a few hundred dollars, money that we could definitely not afford to just throw around. I asked him timidly, nervously, about joining the team and meekly told him about the fee. My dad was more excited than I was. I could not believe it. My father — serious, hard working, and no-nonsense — fell in love with the idea. With this, my education could be complete. My dad dug out his old black Adidas cleats from his high school days and gave them to me. I wore them the entire season.

My father and I finally had common ground. I always tip-toe around the term “Daddy’s Girl” because that implied being spoiled and my father did not believe in spoiling kids; he’d be damned if his kids turned out to be brats. I have always wanted to make my parents proud of me. I was good, and I liked being good, but being good held our relationship at arm’s length. I handed him my report card. He handed back a sticker and a hug.

When I became a high school freshman in 2010, my school established a high school sports program for the first time in its history. The first sports teams established were men and women’s soccer. I tried out and was named a starter for the Varsity team. I worked hard every day at home, at work, and at school. The pitch just became another place to work hard. Working hard was expected of me and it was something I expected of myself. Around this time, my grandfather retired from his job at the bus station at the age of eighty; my dad also underwent a career change for the first time in decades and went to work at a magazine company with his oldest brother. These changes did not go by without notice in the Vielma household. My dad was the “new guy” for the first time in decades.Yet no matter how busy he was, no matter how swamped with work or stress, my dad was always available to talk to me. And I did talk to him. I complained about my coach, about my teammates, or I recounted some funny story that had happened at practice or I told him about the away game. It was important to talk. With few exceptions, my dad attended every home game I ever played. Rain or shine, he was there in the stands, shouting occasionally, and armed with a Gatorade for me to chug at the half.

***

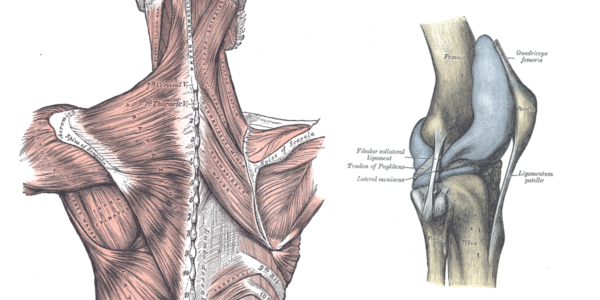

On January 29th, 2013, during my junior season and my sister’s freshman season, I tore the lateral meniscus in my left knee and my sister cracked her L-5 vertebrae in the same game.

It was a terrible game. Someone sent the ball from the right side up to center, two players danced for possession and one went down. It was a spectacular fall, a stunning collision between body and ground. I missed it. I was too busy following the ball, strategizing, focusing. It was the referee’s whistle that snapped my eyes back to the player on the ground and it was the screams that made me realize it was my sister. She lay prostrate on the ground, face up, eyes closed, tears pooling, feet twitching. I dashed to her side, beating the school medic and my coach. “Ana, Ana, Ana, Ana.” I squeezed her hand. “Can you move your feet? Can you move your feet?” She groaned. The medic yelled at me to leave. The game paused; Ana laid on the ground. The players milled around, our cleats dragging through the dirt as we waited out the little purgatory. My sister was helped to her feet and walked off the field. The crowd applauded. The game continued, three minutes left. The referees blew the whistle for the last time and I hobbled over to high five the other team.

“Good game, good game, good game, good game, good game.”

My sister bawled on the sidelines, stretched out and face down on a bleacher. Ice burned cold on her back. I remember lying down on the dry, dead grass at the end of the game in the middle of the field. Our coach yelled at us, congratulated us for trying and said we’d do better next time. I sulked in silence and started crying. My teammates stood up and I realized I could not. My left knee was swollen like a ruby red grapefruit and I could not bend it, let alone support myself with it. I was physically unable to leave the game, and mentally unready to process the loss. “Coach,” I whimpered, “I can’t get up.” I was carried to the sidelines and collected by my father. He carried me to our car, bridal style, and then brought my sister. He told us we needed to start a diet. We laughed and then we cried in the car, physically exhausted. The human body continually astounds me.

These kind of stories are usually dramatic, the sacrifice ultimately being worth it, the game being won by the skin of our teeth. But we had lost, 5–0. After X-rays and CAT scans and doctor visits, my dad told us we were both out for the season, without question.

It was a hard pill to swallow for me, as I felt like I should’ve been able to work through my pain. My sister could barely stand or sit for more than ten minutes before the pain became intolerable but I could walk around just fine after a week in a wheelchair and few more weeks on crutches. My knee swelled when I ran and my kneecap popped out of place but it was nothing that I knew I could not work through. When it rained, my knee was just useless, overcome with a throbbing pain that not even six hundred milligrams of Advil could combat.

My sister and I know how blessed we are, especially her, to be able to walk without as much pain now and engage in a pick-up games. Everyone has heard the stories of injured athletes who require multiple surgeries and months of rehabilitation just to walk, and stories of those who end up living their lives in wheelchairs. It’s a sobering reality to think about. We know how lucky we are and we still caught each other crying softly, quietly, secretly, afterwards. Endings are always sad. I couldn’t tell my dad about practice anymore. I had no funny stories. It was the end to a golden time.

***

“Years have gone by and I’ve finally learned to accept myself for who I am: a beggar for good soccer. I go about the world, hand outstretched, and in the stadiums I plead: “A pretty move, for the love of God.”

And when good soccer happens, I give thanks for the miracle and I don’t give a damn which team or country performs it.”

-Eduardo Galeano, Soccer in Sun and Shadow

Like Galeano, my father is a beggar for good soccer. During the 2010 World Cup, I asked my dad what team he would be supporting. A common question in our family: Team USA or el Selección? He told me: “I’m cheering for good goalkeeping.” I reflect on that moment now and see my father for who he is and who we both are: players, fans, beggars for good soccer.

I was sad when I could no longer tell my father about practice or games.There were often fights over my physical capabilities after my injury, with me assuring him that I was well enough to play and my father assuring me that I wasn’t. Soccer had strengthened our relationship enough that it was able to withstand the fights. Soccer helped me build other bridges with him and when one collapsed — there were other avenues, other common ground that we had found because of soccer.

When my sister informed my father last year in October that she planned on trying out for the team again, he blissfully ignored her. Eventually he sat her down and spoke to her about her priorities and focus. Her focus needed to be academics, college. What was soccer going to give her that she couldn’t find elsewhere? This team was different and the leadership was different. There was no value in it. There is value in playing soccer but she didn’t need to play on that team; the game itself offered joy, why didn’t she just play on her own? For the first time, my father was against soccer, and so was I. I was vehemently against the idea and my sister knew it. When the subject came up at home during winter break, it was a precarious push and pull between us, neither one of us wanting to say too much or go too far. I myself have problems playing even today; how could Ana, who was injured much worse than I was, expect to be able to play again? I returned to school before her season began. Ultimately, my father respected my sister’s decision and allowed her to make her own choices.

Intellectuals have often tried to dissect soccer, its fans and all its idiosyncrasies. Vargas Llosa saw it as a respite from the quotidian, but it is exactly this that causes some critics to see soccer as deplorable. It alienates the masses. It alienates us in the Marxist sense of the word: we do not realize that we are just cogs in the machine; we are socially estranged from aspects of humanity’s natural life. Critics argue that we become so engrossed in the sport that we do not always see or prioritize the factors at play outside of the game, such as corruption, human rights violations, violence, and drug trafficking, all of which heavily influence or profit from soccer. In his essay “The Sporting Spirit,” Orwell writes how he believes that the competitive nature of sport lead to “orgies of hatred.” He is amazed at the public’s perception that sport creates goodwill between the nations. Vargas Llosa tells these critics that they forget that it is important to have fun, criticizing the idea that it is simply a distraction of the masses.

My sister and I had begun placing much more value on games than what they’re objectively worth. My dad’s and my elevation of soccer as an important art compelled Ana in a similar way. Unlike earlier in my life, I had reached a point where soccer was distancing me from my sister and father. For the first time I saw the machine and I was repulsed. “It’s a game,” I would tell her, feeling like a traitor to the beautiful game, “Why would you risk your body for that?” But Ana felt the love and she followed it and once again took up the mantle of #4 on the field.

***

On January 23rd, my dad called me. “Don’t freak out,” he began. I sat down on my couch. His voice sounded tinny on the phone. Ana had an away game, four hours north of our hometown, in San Antonio, and she was in the hospital.

While my sister was pumped with morphine like a balloon and my father drove 235 miles, I shuffled through the snow to pray in the University Chapel. Two thousand miles away from the nurses who meticulously cut off my sister’s jersey, I prayed that my father would not get a speeding ticket. I prayed my sister could move her feet and that the hospital staff gave her lots of blankets, because Ana gets cold really easily. When I left the chapel there was still so much snow on the ground but I felt numb.

She texted me, “I was playing and I was flipped and fell on my back they did xrays and dad is driving up for me.”

“I know,” I texted back.

My sister called me and I could hear her crying. “Breathe,” I told her. “I fractured my T-12,” she cried. These kind of stories are usually dramatic, the sacrifice ultimately being worth it, the game being won by the skin of their teeth. But they had lost, 3–0.

“Have you told mom and dad yet?”

“No.”

“Okay.”

My dad was still two hours away. Is ignorance bliss or torture? I don’t know. I did not tell my parents. I don’t want to imagine what nightmares clouded my mom’s mind as she waited at home. I don’t think about the thoughts that raced through my dad’s mind as he raced on the freeway.

***

“If I were home, I would paint your toenails for you,” I tell my sister. She smiles sadly. “You can survive everything but the last thing,” I tell Ana this over FaceTime, as she scrunches up her face, clearly in excruciating pain.

“This is not the last thing.”

***

Three months later, my sister sits in the seat next to me on NJ Transit and we are on our way to New York City. It is Ana’s first time visiting me and her first time in New York. She stretches out into the aisle. “Does your back hurt?” She nods. I give her Tylenol. It is gray and raining outside but it is not snowing and it is warm. As we get closer to New York, the excitement is palpable. New York is magical for her.

I watch her face light up when she sees the skyline and I think about the moments my father has been most proud of us. I think of every time I scored a goal when I returned to the team my senior year. Each goal was a victory for both of us. I think about the moments I have been most proud of my sister and I think about the moments of quiet when she is walking beside me, each step a testament to her strength and a victory for our family.

If our times are truly characterized by the disenchantment of the world, as Weber said, then soccer is here to save us and offer a respite from the rampant rationalization of life. Like New York, it is a part of the magic that subverts the disenchantment of the world. And to Orwell, who wrote. “You play to win and the game has little meaning unless you do your utmost to win,” I say: you do not know my sister.