Siken’s Fables: Putting on the Wolf Suit

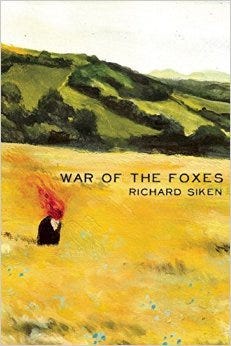

War of the Foxes

by Richard Siken

Copper Canyon Press

April 2015

You know the old fable. The arrogant hare challenges the tortoise to a race. The hare runs too quickly, and while he takes a nap, the tortoise passes him and crosses the finish line. Slow and steady wins the race.

Here is another, more intricate fable:

Tonight, by the freeway, a man eating fruit pie with a buckknife

carves the likeness of his lover’s face into the motel wall. I like him

and I want to be like him, my hands no longer an afterthought.

And another:

A man saw a bird and wanted to paint it. The prob-

lem, if there was one, was simply a problem with the

question. Why paint a bird? Why do anything at all? …

Blackbird, he says. So be it, indexed and normative.

But it isn’t a bird, it’s a man in a bird suit, blue shoul-

ders instead of feathers, because he isn’t looking at a

bird, real bird, as he paints, he is looking at his heart,

which is impossible.

These excerpts, from the collections Crush and War of the Foxes respectively, get at the core of Richard Siken’s epic, twisted poetry. For both collections, Siken’s style has been described as obsessive — over images, bodies, moments. In addition, he writes poems that have much in common with prose, often telling stories with characters and plots that can be traced throughout. Yet, the most interesting way of looking at these poems comes from Siken himself, who explains his work as “anchored by several prose poem fables.”[ref]http://bwr.ua.edu/an-interview-with-richard-siken-judge-of-bwrs-2014-poetry-contest/[/ref] At first, this label may seem inappropriate. Fables are typically intended for children, and serve to teach a simple moral. In contrast, Siken’s poetry deals with mature subject matter, and is often lacking what would be considered a succinct lesson. Yet, his poems are still strikingly similar to traditional fables. As evidenced by “The Tortoise and the Hare,” the traditional structure of a fable involves introducing a misconception or assumption and turning it on its head to impart a lesson. Siken uses this forms to beautiful ends by introducing a scene and challenging everything taken for granted about it. He dissects the truth then dissects the dissection. Consider the first excerpt, from the poem “Little Beast.” There is a man eating fruit pie, not with a fork, but with a knife. Nor is he happily enjoying his pie; he is stabbing a motel wall. However, according to the speaker, this action is not destructive. His love, this place, both temporary, have now been made permanent. Here we find the moral: he is doing something useful with his hands. Another element of fables present here is violence between predator and prey, or the act of consuming. Think of such fables as “The Deer with No Heart” or “The Boy Who Cried Wolf.” From the title of the poem, “Little Beast,” the man and his lover are characterized as animals. The act of eating a pie butts heads with destructive romance, as if to say that love itself is consuming, even predatory. This battle between love and death, so reminiscent of fable, is truly what “anchors” Siken’s work. However, the ways in which Siken presents this relationship mutates and metamorphoses throughout his work, specifically between his two published books.

Based in Arizona, Siken works as a poet, photographer and filmmaker, and editor for the Spork Press. His collection Crush came out in 2004 as a winner of the Yale Series of Younger Poets prize. It became a sort of cult classic, partly due to its harrowing insight into issues faced by the gay community. Certain lines have even inspired the occasional tattoo. Fans had to wait a long time to hear more from Siken. His next poetry collection, War of the Foxes, just hit the shelves earlier this year. I was first introduced to Siken’s work two years ago. Still, even without experiencing the ten year gap, I appreciate the evolution that has occurred between the two works. Siken is still, undoubtedly, Siken. He is simply fighting different battles.

The speaker of Crush is nearly driven mad by his inevitable death. In his fear and fascination with dying, his life becomes an experiment in living on the edge of destruction. For example, in “The Torn-Up Road,” the speaker begs,

Tell me we’re dead and I’ll love you even more.

It is as if the speaker cannot enjoy love knowing that it will come to an end. To completely understand this frame of mind, we can look forward to “A Primer for the Small Weird Loves”:

The blond boy in red trunks is holding your head underwater

because he is trying to kill you,

and you deserve it, you do, and you know this,

and you are ready to die in this swimming pool

because you wanted to touch his hands and lips and this means

your life is over anyway.

Though not autobiographical, it is clear that Siken’s motivation for writing Crush was partly to illustrate the psychological effects of being gay in an unwelcoming world. Siken creates a character who has had many experiences with rejection, which are often violent. Because of this, the character imagines himself as a sort of predator, whose sexual desires make him a monster who ruins everything. So, those who claim that Siken’s work is melodramatic would be correct. However, this does not invalidate the work, because it is what the situation calls for. Siken is giving a voice to the very sad phenomenon of gay people who grow up thinking that they are “bad” by nature and that it is their fault. The speaker is constantly struggling against this reality, like in “Litany in Which Certain Things Are Crossed Out”:

I’m not really sure why I do it, but in this version you are not

feeding yourself to a bad man

against a black sky prickled with small lights…

Here is the repeated image of a lover destroyed.

Crossed out.

and

We clutch our bellies and roll on the floor’

When I say this, it should mean laughter,

not poison.

Yet perhaps more poignant than the desperate panic of the book’s majority is the turning point that occurs in the final poem, “Snow and Dirty Rain”:

We’ve read

the back of the book, we know what’s going to happen.

The fields burned, the land destroyed, the lovers left

broken in the dirt. And then it’s gone…

But there’s a litany of dreams that happens

somewhere in the middle…

We are all going forward. None of us are going back.

At last, Siken’s lover steps back and takes a breath. This turning point is why I now perceive Crush as unfinished, and War of the Foxes as a continuation. Finding the strength to forgive himself, it seems that there is something more that Siken can say.

For, while War of the Foxes is still concerned with death and love, there is an added element that builds upon the line “we are all going forward.” War, as would be expected, is omnipresent in these poems. In fact, it becomes synonymous with almost any action. From “War of the Foxes”:

Let me tell you a story about war. A man found his

life to be empty. He began to study Latin…

Let me tell you a story about war. A man had a dream

about a woman and then he met her…

Let me tell you a story about war. A fisherman’s son

and his dead brother sat on the shore…

In this manner, human pursuits are battles, and much of the book is spent dissenting how these battles are fought. But to what end? Siken answers this with the refrain, “Everyone needs a place.” This place, as hinted at in the poems, is happiness, belonging, and purpose. Everyone is fighting their own battle in this same war. In “Detail of the Woods”:

What else was in the woods? A heart, closing. Nevertheless.

Everyone needs a place. It shouldn’t be inside of someone else.

Here we see how Siken’s new voice differs from Crush, whose speaker bases his self-worth completely on the acceptance of others. In contrast, War of the Foxes focuses on how individual people, objects, or concepts are useful. So perhaps this “place,” this usefulness, is in fact the “litany of dreams that happens somewhere in the middle” mentioned in Crush. The reader knows that despite the broken glass and predators, despite our inevitable destruction, one has the power to create that “gold room where everyone finally gets what they want.” He eliminates excuses in “Self Portrait against Red Wallpaper,” saying,

What would a better me paint? There is no

new me, there is no old me, there’s just me, the same

me, the whole time. Vanity, vanity, forcing your

will on the world. Don’t try to make a stronger wind,

you’ll wear yourself out. Build a better sail. You

want to solve something? Get out of your own way.

Thus, there is great satisfaction after reading War of the Foxes. Its verse cradles the same photographs, of apples, of the moon, of restless birds, and whispered italics as Crush. It is narrated by the same searching artist. Yet, our hero has been liberated from self-doubt, finally able to participate in the world without the pretext that it is a place he does not deserve. Without constraints, the themes of Crush are examined anew under a wider lens.

Where, then, will Siken go next? Throughout War of the Foxes, Siken is perhaps trying to tell us that poetry, his war, his purpose, will never be finished. The speaker of the poems says both “I surrender/my desire for a logical culmination” and “Never finish a war without starting another.” Like his flawed fables and paintings, writing poetry is a process that will never completely satisfy its writer. In the book’s final poem, “The Painting That Includes All Painting,” Siken asks,

The central panel now missing —

We all dream of the complete document, the atlas of the idea,

the fish on the table finally gutted —

What does all this love amount to?

Putting down the brush for the last time —

Closing his book with “Putting down the brush for the last time — ” is at the same time so final and so unfinished. He knows that there will come a point when he has written his last verse of poetry. He also knows that his work will never be perfect. Yet, with the Dickens-esque dash hanging at the end of the last line, the reader knows that this is not the end of Siken’s attempt at making his place in the world. The war, the powerful play, goes on.