Excavating Home

Promises, Ghosts, and Memories

by Staff Writer Simone Wallk

We wander the desert barefoot, hands sticky with dates and mouths smeared sweet and pink by pomegranates. The landscape bloom paradise on its humpback hills.

Beyond the fertile peaks lie scorched sands, expanses of stone cooled by salty sea spray. The breeze of the valley rustles olive branches, blessing the dust in clusters.

This land of milk and honey is pure, with trees so ancient their gnarled roots trace directly to knowledge and life. It is a land much desired, the object of centuries of longing, tears, and prayer. It is the promised land.

Promised land, not lands. It is the singular place pledged to our people by God, a geography of freedom and salvation. In its existence, desires long-held may still be fulfilled. This utopia of liturgy and culture has been realized in the form of a nation-state, and it struggles to fulfill two thousand years of exiled expectations. Should one mourn for the soil of salvation, burdened by blood and oppression that run like groundwater? This land is sacred and defiled at once.

“There was nothing but land; not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made,” writes Willa Cather in My Antonia. Cather’s land is not dry and hilly, but expansive and uninhabited, the great frontier of grasses that wave and roll with the wind of the American plains. In this remote corner, she paints pioneer life with the tinge of loneliness; “of all the bewildering things about a new country,” she imparts, “the absence of human landmarks is one of the most depressing and disheartening.”

Of course, the plains were not uninhabited when Cather’s ancestors arrived six generations earlier. Her biographers dispute her relationship with the Native Americans of the region, yet Cather’s own respect for land, and perhaps even her method of storytelling itself, seem to pay homage to the peoples her family displaced.

I do not use the word “displaced” as a judgement, but as a fact of history. I believe the movement of peoples may be just as redemptive as it is blue. But autonomy and responsibility for this movement define personhood; without that agency, we exist at the mercy of others.

My heritage is colored with a fusion of forced and free movement, a lineage of wandering. Perhaps I romanticize forced migration with the word “wander,” because these journeys were not leisurely, certainly. They took place in last-train-out-of-fascist-Ukraine frenzy, in the chaos of severing ties that comes with false belief in home. On midnight trains filled with livestock, the stench of animal dung and throbbing hunger are not leisurely. Nor casual. But aimless this wandering was. Rather than following the veins of prayer and longing to homeland — the land of milk and honey — these trains left Ukraine for Siberia and Uzbekistan, safe havens of circumstance. It was the final refuge, the United States, that my father sought with unique purpose. My father, who grew up idealizing American freedom in Soviet Russia. He choose this home over the original promised land, and in a strange paradox, implicated our wandering family in this country’s story of forced migration.

One imagines the imprint of the prairie on Cather as a palm pressing clay, imprinting subtle lines and deep caverns. Infinity links soul to place, an eternity of memory absorbed, of minerals and fruits ingested, of groundwater that integrates with body, of knowledge of direction and demography. These unending links exist in this land of rolling wheat, for Cather, where six generations of family were birthed on one farm. I do not know where, if any place, the infinity of my wandering people exists. Surely not in the plains of Central Asia, where the years of my grandmother’s adolescence were spent farming in a kolkhoz (collective), a novel task for an urban Jew. Perhaps in the shtetls of Eastern Europe, the longest lasting of these homes, or in the Fertile Crescent, where I imagine my very early ancestors survived the first of many exiles, cultivating a new sense of “holy” outside the promised land. It is unnerving that I will never know the paths and places running within my blood, only that my infinity of place is disparate.

Without deep physical ties to one land or another, the spiritual connection to the holy land strengthens. Each migration, each riot or expulsion, wounds tighter the tether between soul and promised land. While the soul longs for the stability of the eternal homeland, it nevertheless seeks belonging in its temporary home. The traces of place, then, inside my body and my psychology, may be echoes of that internal dissonance, a paradoxical longing for and wandering from one’s promised land in search of home.

I grew up on Lake Michigan, in the city of Chicago, a name that means “wild onion” in Miami-Illinois. Upon saying that I am from Chicago, the inevitable follow-up relates not to the city, but its suburbs. People who look like me — white people — are not usually associated with Chicago: not today, at least, when it is narrated through stories of gang violence and guns. This misrepresentation is, I believe, a manifestation of alarm and distress, which capitalize on the terror and transmutability of real violence to justify segregation. Yet despite my caution not to believe this curated story, I find this city to be a place of great discomfort outside of the small sphere of neighborhoods where I have been raised. My uneasiness is an unfortunate casualty of fear and conditioning, the guilty vestiges of place that I appear to be internalizing. It is a biological fear, through adrenaline and epinephrine that rush when I venture outside the grid of streets deemed “safe” for a woman of my skin color. Underlying this trepidation is a sense of great guilt for my position of power in this landscape.

In an attempt to better understand my mental association of Chicago with “home,” I often walked through unknown areas of the city. Segregated by boundaries of color, these places further rendered my identity as a Chicagoan fraught. I did not know the terrain, and experienced novel languages and cultures as well. Logically, I believe this diversity is one of the great wonders of urban living: the presence of “others” that feeds a culture of exchange and intersection. What a shame that American hyperconsciousness of racial purity, fear of the other, and exclusionary policy make home unknown and neighbors foreign.

Upon returning to the city after spending a summer in Israel, I began to better understand the problem underlying these urban explorations. My summer in Jerusalem was framed by the poetry of Yehuda Amichai, an Israeli writer born in Germany. In “Tourists,” he describes the commodification of Jewish history and spirituality by visitors to the promised land who “put on grave faces at the Wailing Wall” and “laugh behind heavy curtains.” The narrator, on the steps of King David’s Tower, becomes a target marker for the visitors’ exploration of place; “Just right of his head there’s an arch from the Roman period,’” says their guide. I had been conscious of my status as a tourist in Israel, intentional about initiating conversation to understand the essence or history of the land — through its people, not its places. In Chicago, I had ignored living people, concerning myself with subway stops and neighborhood boundaries. How could I expect to understand home without interacting with its inhabitants?

In Amichai’s words, tourism in Israel is an expensive act of mourning, a pilgrimage to museums, cemeteries, and battlefields memorializing the dead. This trend may not be so modern, in fact; Judaism rests upon great concern for the traditions, laws, and eternal home of those deceased. In centering life in this world, our culture stems from the ghosts of matriarchs and patriarchs who haunt text and land alike.

Through her writing, it is evident that Cather felt deep communion with the creeks and grasses of the American West. In one understanding of history, Cather’s nation — the United States — quite literally stole these places of great beauty, manipulating inhabitants who did not believe in ownership of land. Earth, said Crowfoot, chief of the Siksika Nation,

will last forever… As long as the sun shines and the waters flow this land will be here

to give life to men and animals. We cannot sell the lives of men and animals;

therefore we cannot sell this land. It was put here for us by the Great Spirit and we

cannot sell it because it does not belong to us.

Land, geography, Earth, home — it does not belong to anyone, Crowfoot implies. Spirited like the human soul, it persists in an atemporal, enduring state.

Like the lands of Alberta, the geography of Nebraska was intimately known and cared for by Native peoples, whose tribal names have been replaced by Czechs, Swedes, and Germans in Cather’s work. Her words embody the timeless advantage of the victors of history, who inevitably bury the narratives of those they have evicted: all these ghosts. Surely the reluctant footprints scarring this soil impact the psychology of the place I now know as “home.”

Where do these vestigial peoples lie latent — these ghosts, spirits of history, remnants un-remembered and un-memorialized? How are their memories, so purposefully buried, transmitted form generation to generation?

The tenacity of these ghost stories is something to wonder at; somehow we continue thinking of people long gone despite significant efforts to place them, physically and mentally, out of mind. Perhaps this is because we carry these ghosts, as Carl Jung theorized, mentally. They inhabit our collective unconscious, a “second psychic system of a collective, universal, and impersonal nature which is identical in all individuals.” Our psyches and our bodies are plagued by inherited fears, desires, and histories; the “psychic life of our ancestors… compromises the freedom of consciousness.” The most basic emotional responses are evolutionarily hardwired and inherited from our culture, Jung suggests. And the ghosts, then, which come before us in history or entirely separate from us in lineage and place, may nevertheless form archetypes within us. We do not have the ability to escape our consciousness and reject these memories.

Land, in this sense, comes alive. And within its history are the individuals — the ghosts — who shadow memory into reality.

The promised land lives in many minds — longed for, sought after, cursed, coaxed into existence. In its physical state as a sliver of desert and coastal plains and mountains, it seems at once enormous and puny, a nation fragile in its contradictions.

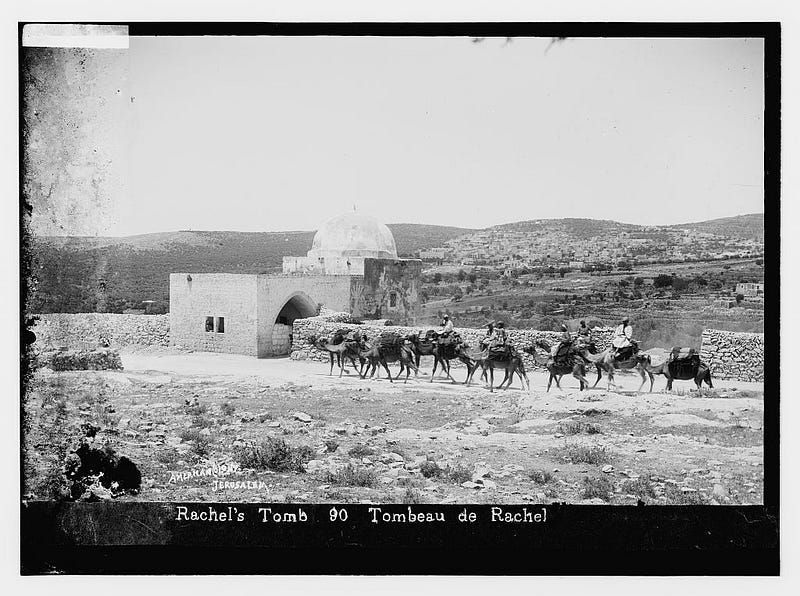

By excavating stone walls and villages from the ancient eras, the Israeli government hopes to find proof that the land is haunted by Jewish dead. Dotting the landscape, archeological sites are adjacent to refugee camps and makeshift borders; one only has to visit Gilo, in East Jerusalem, to observe this strange juxtaposition. Located across the Green Line, the area is swallowed by the separation barrier. Ugly and grey, it snakes around the entrance to kever Rachel, the grave of Rachel. A Jewish matriarch, her status as a symbol of our values is ironically enshrined in a wall that deigns some less human than others.

Yet the spirits of the promised land are not only ancient. Many are living today, or at the very least surviving in a state of limbo. Palestinians exist tenuously as beings so politicized they are nearly historicized. The powers that be in Israel will not confirm the humanity of these ghosts, choosing instead to revoke their agency and freedom. They remain living casualties of a land so longed for that eviction and appropriation were undertaken to realize Gan Eden, a biblical, pastoral paradise.

One wonders how such conflict will ever end, if not through burying of narrative and collective forgetting. Kafka began to ponder this question in “Jackals and Arabs,” published in Der Jude in 1917. This short story is remarkably prescient — prophetic, one might say. It is grounded in the visit of a European to the desert, where he is met by the Jackals, die Schakale, a stand-in for the Jews. Swarmed by these animals as if he is their long-awaited Messiah, he attempts to distance himself from their mission, killing the Arabs; “I’m not up to judging things which are far removed from me. It seems to be a very old conflict — it’s probably in the blood and so perhaps will only end with blood.” Blood to blood — this is the arc of the promised land, from holy war to crusade to occupation. The Jackals do not deny the violence inherent in this trend. “‘What you say corresponds to our ancient doctrine. So we take their blood, and the quarrel is over.”’

Violence is often bred in the pursuit of promised land; the realization of homeland may hinge upon rejection of the values that lend home meaning. I cannot imagine the raw geography of grief that mars our world as a result of the universal attempt to establish home.

Perhaps this is why the promised land is not illustrated as a utopia within biblical texts. There, it is the site of war, incest, and shame, but all of these within the context of strengthening the relationship between God and human. Somehow, the reestablishment of this land is one step in realizing a utopian age, a messianic age. It is particularly disheartening that a land of holiness is stained by contemporary violence, one hundred plus years of bloodshed for sanctification. It is a biblical reenactment of sacrifice, to a certain extent, this attempt to make holy through war, staining the pale desert with blood.

Within its two hundred and forty one years of existence as a nation, the United States, too, has managed to produce a cadre of ghosts. We live upon lands cherished by Native Americans, revere buildings constructed by slaves, and economically rely upon a caste of ghosts-in-formation in the form of migrant labor. Their limbo is contrary to the values of our nation and intentionally buried in the process of history, with which we are all complicit.

It seems as if the oppressed continually become repressed, quietly enshrined in the places around us — the places of great meaning that we consciously choose to disguise, bury, or appropriate. This exchange between place and ghost is the foundation of Toni Morrison’s work, an oeuvre that explores the shadows of history, family, and America both intellectually and emotionally. In Beloved she writes

Places, places are still there. If a house burns down, it’s gone, but the place — the picture

of it — stays, and not just in my rememory, but out there, in the world. What I remember

is a picture floating around out there outside my head. I mean, even if I don’t think it,

even if I die, the picture of what I did, or knew, or saw is still out there. Right in the place

where it happened.

Haunted places, Beloved expresses, are inescapable in a nation like our own, where the dead of slavery lie in nearly every state and county. The memory of this house, this land not fit to be called home, is collectively existent as well as collectively repressed. Our intention — to forget pain and trauma — is impossible with the magnitude of their reach and the many places they haunt.

After all, the title character of Beloved is a literal ghost, an individual killed by a system that breeds shadows like spores. Ghosts inhabit the minds of the living, sustaining their presence in our lives through remembrance. But physically, the dead return to the ground upon which “home” is built, sinking their presence deep into our contemporary infinity of place.

The act of memory itself, within a culture set upon forgetting, is a distortion, a re-remembering, according to Morrison. We cannot know the truth of the interactions between ghost and ancestor, nor is this the intention of memory. It is the amalgamation of all this grief, dishonesty, and blood that scar the land, breaking promises of virtue. Only through consciousness of our tendency to re-remember can we reclaim its power, shaping narratives of home to include those long forgotten.

From Israel to the United States, the retelling of our universal ghost stories is limited in part because the act of memory is emotionally draining. Echoes of force and movement ring clear across the Midwestern prairie and the dunes of the promised land as we stutter to draw words from submerged memory. Still, I am emotionally hesitant to agree with Cather, who, in O Pioneers! writes, “there are only two or three human stories, and they go on repeating themselves as fiercely as if they had never happened before.” Should ejection of other peoples be the human story, this earth will sink with the heartache of leaving home.

Is this part of our biology, this territoriality, exclusion, and overgrowth? However comforting it is to believe that displacing others is a function outside of our control, this mindset excuses our responsibility for willfully hiding these histories.

It is undoubtedly complex, this telling of stories of place, because they are so essential to our identities. We craft stories to justify the twisted histories of places held dear, as Cather prescribed; “let your fiction grow out of the land beneath your feet.” Our narratives, promises, and stories, whose reality can never be recovered objectively, are perennially revised as claim to homeland.

How do we tell these stories? While excavating bits of the promises that so tenuously frame our narratives of home, I struggle to properly name places. In describing a place with its name, I intend to refer to physical space and geography. There is a precise method for distinguishing between physical and political in Hebrew, where eretz yisrael labels the land of Israel and medinat yisrael identifies the kingdom or state. Calling the promised land “Israel,” despite the biblical significance of this proper name, seems like a politicization of earth. We were not promised a nation state but a physical geography, and I tend to believe that the paradisiacal gan eden of the eretz will not be institutionalized. I am challenged, too, when describing the United States/America. Calling this place the States seems to concede to the institutionalization and systematization of land, but naming it America places claim on a whole continent — itself an expansionist act I do not wish to perpetuate. Somehow the English language does not seem adequate to describe this land unpolitically, simply as a geography.

In Kafka’s prophecy of Zionism, the Jews-turned-jackals do not hesitate to make the ultimate request of their European visitor. “That’s why, sir, that’s why, my dear sir, with the help of your all-capable hands you must use these scissors to slit right through their throats,” they ask.

It is a simple idea, but nevertheless dark: bloodshed will end a quarrel over land. Darker still is Kafka’s point that such a mission turns human into animal. Our animal nature is veiled in centuries of sophisticated stories that obscure our lust for space. In longing for home, we experience a strange confluence of the urge to conquer, to cultivate, and to rest at peace — eviction becomes a sacrifice for psychological survival.

Jews, Kafka seems to hint, are obsessed with death. This is a strange concept to associate with a religion so entrenched in rituals of life. But the Jewish tradition is grounded in ghosts — in the study of history, retelling of memory, and sanctification of the dead. Ghosts are essential to preserving this culture. If the establishment of medinat yisrael is another effort in that spirit, why do we generate a new class of ghosts in the process?

As a child I often enjoyed listening to the narratives that frame these places, my homes suspended at six thousand miles away. I spent many hours reading stories from an illustrated version of the Jewish Torah, learning about the foibles and conquests that define the promised land. Exploring the American narrative concerned me less as a child. Then, in high school, I was taught of our religious origins as a “city on a hill,” a Puritanical light among nations. In fleeing Soviet religious persecution, my family fulfilled that mission. It is a strange coincidence that both Israel and the United States are covenantal nations, divine places of promise. Blessed land, it seems, is easily violated.

The promises of our covenants necessitate the telling of stories; the land becomes less sacred if we do not remember its purpose. Any story, of course, involves selection and exclusion of details. But the patterns of our choices in crafting narrative, from generation to generation, create a culture of silence. We blot out the narratives of guilt, burying them deep within our collective unconscious. In America, this phenomena embodies our efforts to believe in, or to sell, our exceptionalism. In Israel, storytelling appears to be more honest. I speak as an outsider, as someone who does not speak Hebrew fluently and has not spent significant time within Israeli culture. But Israelis, embedded in the Jewish tradition of retelling, do not hesitate to reflect on the past. It is the recent history, and the present, that is entombed by mouths and ears.

Home is naturally associated with comfort and peace. But the land upon which many homes are constructed is composed of violence, injustice, and unreckoned memory. Promises are broken in the name of holiness. Scar tissue accumulates where milk and honey once flowed. Culture becomes laden with the latent memories of people displaced and oppressed. Yet even land battered and breached continues to fruit. In its resilience, its tenacity to produce the good and beautiful from dust, land makes promises anew.

Even while attempting to reckon with the ghosts of the places I call home, I find myself caught in the trap of denial and exclusion. I am eager to deny ownership of the ghosts of the United States, reasoning that the absence of my ancestors from this land nullifies my association with these spirits. Likewise, in the present, my absence from Israel facetiously excuses my responsibility for the occupation ongoing in the promised land. I do not truly believe in my innocence. These ghosts inhabit the stories I treasure so dearly, in my culture and our collective memory. If I choose to engage in any retelling, I cannot ignore their presence. Yet the prejudice and pain persist in re-remembering, even with the artifice that our words create.

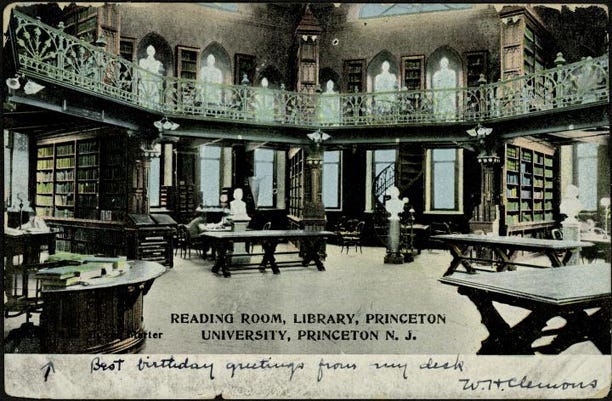

Here at Princeton, I am just a few months away from Chicago and the very notion of home is becoming intensely psychological. I feel distraught about the many promises that are being broken in the promised land, the violated visions of peace and sanctity. I feel ignorant of the realities in Chicago, my city, a place I know intimately and find foreign all at once. And I have yet to explore the contradictions that inhabit Princeton, a place with its own history of silence. The ghosts in each of these homelands remain in my heart and in my head, a vestige of land. Through the process of rememory, I seek some way to sanctify their presence, ensuring that they remain honored in the infinity of places for generations to come.