The Mad Girl and the Dog

by S.M. Joseph

The period of my father’s downfall can be marked by three instances: the arrival of Raina in my life, Peter Augustine, and the nightmarish metal horse at the mouth of my driveway. My father bought the horse from a cancerridden Polish artist on the way to work. I am not sure why he bought it because it is hideous — looking like a junkyard project, or a novelty postmodern barbecue — but he did, for five grand. The artist also offered to take my father to Poland where he could teach him how to live on just five dollars a day. Perhaps this was the horse’s seductive appeal. Its rusty limbs took bleak connotations in my father’s mind: visions of trudging through stark Polish lands, touring death camps, his face numb with frostbite. A vague, black space of the psyche: maniacal laughter, madness, and the dark side of the moon.

Now the horse guards my mailbox like the Grim Reaper, having descended on my New England neighborhood. My sister almost backed into the horse with the car, to my great delight, but it was probably good she pressed the brakes because the car would have fared worse than the horse. My mother rationalized the horse as avantgarde — we were a family of trendsetters, living on the cutting edge.

Unfortunately, my dear mother, those on the cutting edge tend to bleed the hardest. —

There is crazy in my house — in the shelves of books about serial killers, in the fungi flourishing in my home’s damp bowels, in the Tylenolpink nightgown encasing my soft and hairless father. I love him dearly but can no longer conflate his image with the Father Almighty in the unconscious tradition of most good religious folk. He has lasered the hair off his legs and arms and turned as sweet and tender as a newborn rat. My mother thinks his nightgown is “too girly.” In my eyes, the real problem is aesthetic: the pink flannel clashes horribly with the dark wine in his hand.

My father is telling us about Peter Augustine, whom, like the Polish artist, he met on the way to work. Peter Augustine is also crazy. He lives in a decaying wooden house splotched with pseudoNietzschean sayings: God is dead, to thy own self be true. Like a dying man to an oasis, my father was drawn past the picket fence that rotted like a row of teeth. He knocked — a fateful knock that resounded in the house’s murky interior, rattling the windows. The door cracked ajar to reveal the bearded face of Peter Augustine, who beckoned my father deeper into the gloom.

In his basement, Peter kept a lopsided boulder that he rolled around the home’s foundations to ward away malevolent spirits. He let my father tumble the boulder around the room for two and a half laps. He then took my father up a creaky flight of stairs to the attic, where he stored his collection of chainsaws used to whittle voodoo dolls. How he carved petite dolls with giant saws, I do not know, but this was the way of Peter Augustine. The dolls were to be placed by a computer to keep away viruses. Peter sold my father two for thirty, buy one get one half off.

The following scene is movievivid in my head: the attic’s dreary light, the dishes stinking in the sink, my father marveling at the doll’s heavyhewn limbs, and Peter Augustine with his cragglesmile and filthflecked beard leering behind him, brandishing a chainsaw. My father claims he could have easily died right then, if Peter Augustine had been a murderous psychopath. But thankfully for my father, who speaks of his almostdeath with unrestrained glee, Peter Augustine is a different kind of crazy: the crazy of a shaman. Every morning he sits on the grand steps of the Capitol Building and wards off terrorist attacks with his mind. At this point of his tale, my mother (who I gotta say has been holding out pretty well so far) scoffs and rolls her eyes. But nonetheless — my father insists — Peter Augustine is the real deal, a true practitioner of the mental martial arts, and my father paid him five hundred dollars for his expert instruction.

And so Peter Augustine begins mailing us lessons typed in a spooky font downloaded from the Internet. His first dictum? For thine enemies do not reserve a single neuron of thy brain. Power is diminished through negligence. Or something. In the following week, my father will hold himself accountable for the dismissal of two racist coworkers, banished in the Valentinian way.

He keeps insisting that I should visit Peter Augustine’s myself — the temple of prophets and gods.

I don’t want to visit Peter Augustine. I am scared that I’m going to catch the crazy like the flu. Maybe that is why I am so distant to my father’s coworker Raina when she first enters my life. Like all my father’s associates, she reeks of crazy. Highcheekboned and over sixfoottwo, she wears lavender Uggs, smokes a vanilla vape, and drives a Tesla that was twice struck by lightning. She was unharmed and sued the company for lots of money, and I’m not really supposed to talk about it.

My father and Raina commute from the subway to work together, where they write programs for an IT department. They walk nine Cambridge city blocks that I instead imagine as a Google DeepMind dreamscape, crowded with raving prophets and sickly artists and horrific metal animals the size of small elephants. My father takes small quick steps, wearing a plaid jacket. Raina hums and skips in giant giraffelike bounds. A crew of construction workers gapes at Raina because she used to be a man, and for some people, her exmanness is the first thing they see. I do not realize she used to be a man until I hug her augmented abdomen, and then my father tells me.

My mother, on the other hand, notices immediately. She says that Raina takes more dominating positions and smokes her vanilla vape just like a man while talking to my sister or me. Our femininity brings out her masculinity, according to my mother, but I’m honestly not so sure.

Raina has ADHD and narcolepsy and cyclothymia and depression and psychosis. Along with the hormone therapy, she’s been prescribed a convoluted recipe of medications that costs ten thousand dollars a month. When we first meet, she pulls out a plastic orange canister stamped METHAMPHETAMINE HYDROCHLORIDE and asks if I wanted some gradeA, pharmacybrand meth. My father, nesting on the couch, clucks in disapproval and accuses Raina of treating her craziness like a badge of honor. Raina cackles and agrees. Crazy? There is nothing she would rather be.

I ask about the mechanism of action behind her medications. She happens to know a lot of biochemistry and takes a liking to my questions. She says I’m just like my father — I am rebellious. I don’t know how to feel about this and roll my eyes. She goes on to say that my father and I have a hilarious dynamic. By this point, I think she is trying to become my friend. She complains that she does not understand female fashion and has not bought clothes in a long time. I offer to take her to the mall to help her out. She cocks her head, excited, and immediately I regret having asked. Later that evening, I ignore her texts about shopping plans.

I’m being a bit harsh here. I like Raina, I really do. She has edge and doesn’t care what people think. She is a good influence, but only as a peripheral character, so I don’t get sick.

I return to college, a montage of academics and parties, set on a backdrop of plush lawns and Gothic architecture. I go about my life; I forget. I hear trickles of crazy from my mother’s disconnected voice on the phone but keep the conversations short. Summer comes, and blossoms unfurl across campus. My friends and I take long strolls about the greens, sipping the fragrant air. My nights are fueled by champagne, and filled with intellectual conversations and flirtations with straightlaced boys who think I am pretty. There is barely any crazy here.

One day, Raina calls to ask how I’m getting home once college ends. I tell her my father is picking me up in his car. She offers to drive him in her Tesla instead, because she loves making spontaneous road trips. I tell her sure, why not?

There is a bit of bureaucratic trouble here. My mother does not feel comfortable with Raina driving my father to pick me up and accuses him of having a girlfriend. My father spits a laugh, says he would never date someone half his age, and tells my mother to stop being so damn ridiculous.

After my last exam, Raina and my father pull up by my dorm in her Tesla. My father looks even smaller than last time, shrinking into his plaid jacket that he wears despite the summer heat. As he and I load the car with my luggage, Raina sits in the driver’s seat and blows vanilla steam through the window. Her eyes are huge and blue and blank. My father shoots her a troubled look and whispers that she’s not doing so well.

We eat dinner at an expensive restaurant with oaken walls covered in sepia portraits and hunting gear. We are surrounded by upper middleclass families — the welldressed, wellmeaning, slightly awkward kind. My father and I sit across from Raina in a booth. I ask how she’s doing, because courtesy demands so. She says nothing. Her eyes look as if they have been vacuumed of all consciousness. My father prompts me to ask what she did to herself. I don’t want to know, but ask anyway.

She opens her mouth, closes it. Ten — twenty — torturous seconds pass. I ask if she’s on drugs. Sleepdeprived. Experiencing trauma. Just messing with me. She shakes her head no, none of the above. I no longer want to play this deranged guessing game and wait for an answer. My father cuts in: Raina has hypnotized herself.

She nods, her mouth drooping open. As if her lips are made of rubber, she speaks slowly, words clunky. She says that this is a little embarrassing, but she first started with erotic hypnotism. She managed to lull herself into a deep trance, and then the dog appeared. The dog became stronger until it began inhabiting her mind. I ask if she’s serious, but her eyes remain so vacuous that I have no choice but to accept this truth. The dog is female and friendly and taking control of her body. Raina did not drive my father and herself to pick me up. The dog did. She assures me that the dog is a very good driver.

She cannot use her silverware because her hands have been hypnotized into paws. With gluedtogether fingers, she nudges her potatoes around her plate. Now I cannot stop asking questions, feeling obligated to plumb the depths of this medical mystery. Can she hypnotize herself to be a human again? She says yes, but she does not want to, she likes being a dog. Can I hypnotize myself to be a dog? She says that anyone who wants to be a dog can be a dog — you just have to surrender yourself completely. I tell her I could never do that. She goes on to tell me the dog likes me and wags its tail when it sees me. It can also do tricks; in fact, I should tell it to bark. When I say “bark,” Raina begins yowling in the middle of that bourgeois restaurant. My father snaps at me not to egg her on and tells Raina to calm the hell down.

She drives us home in her Tesla, which runs so smoothly it makes no sound. I feel like we are gliding on air. Throughout the six hour ride, she pants with her tongue lolling out and refers to my father as “she.” I tell her that my father’s nightgowns are hideous, and that he should buy some prettier ones from Victoria’s Secret. She snickers. My father laughs too and says that his therapist told him that he is lucky to have a daughter like me. He says that I’m a good girl, although I often lack direction, but I tell him not to worry about that.

My father invites Raina home for dinner to thank her for the ride. He first has me call my mother to make sure she’s okay with it. The voice on the phone says a yes that actually means no, but I tell him that she would be delighted.

My mother is a pretty woman, with hair flatironed into black sleekness. She greets us at the door and ushers us into the dining room, where the table is laden with homecooked dosai, rice, and sambar. The table is far too big for the room. My father chose it because it is round like King Arthur’s and encourages the notion of equality, but my parents, sister, Raina, and I are only five people and sit around it in a lopsided semicircle. Raina warns my mother that she will have trouble eating, because she has turned into a dog. My mother looks dumbfounded for a second, then decides that the best course of action is to treat Raina’s dogness like a bad joke. When Raina paws the rice around her plate, my mother with a ladylike smile applauds her for eating in the proper Indian way.

The rest of the evening goes downhill from there. My father drinks three bulbous glasses of wine and starts a semifascist tirade about Hitler that my mother soon shuts down. He and my sister get into a ferocious argument about the purpose of lesbian scenes in movies. Then halfway through dinner, Raina slides from her chair and collapses on the floor, where she lies on her side, legs and arms splayed in the same direction. My mother forces the rosy laugh of good breeding and asks if her cooking is too awful to eat. But Raina has lost the capacity for English and grooms her hand with her tongue. She crawls through the dimly lit hallways of our home, panting. She nudges that my sister’s hand to pat her head. Finally, her speaking abilities return and she asks me to get her vanilla vape from her jacket pocket, which will turn her human for a little while.

I can no longer bear it. After fetching her vape, I excuse myself, run to my room, curl under my blankets, and fall into a comalike sleep. I forget to thank her for the ride.

Summer is inching along, and the image of Raina and her vacant eyes will not leave me. She sends a couple of texts about an EEG device that she has bought and been fiddling with, but I do not respond. Meanwhile, my household’s rate of alcohol consumption is steadily increasing. The evenings are stuffy and blasting with Beethoven’s music and smelling of sevendollar wine. Outside, the horse stands with a license plate collaring its neck, rusting in the heat, faithful as a dog.

My father one day tells me that Raina has been absent from work for the entire week with no explanation. He asks me to contact her; I call but only get her answering machine. I send her a stream of texts, apologizing for my lack of response and asking if everything is alright.

Her reply comes three weeks later in a series of texts — from the psych ward of Mass General Hospital. She cannot recall what happened in its entirety, but from what she does remember, the dog began messing with time. The dog showed her flashes of the future, which led to an addiction to poker because the dog would tell her the outcome beforehand. Sometimes the dog grew so intense that she huddled against the wall and cradled her head. Sometimes the dog disappeared and left her apathetic for days. And then the dog began transforming, first into a male dog, and then into a human. A man. Raina’s old self had returned, and he wanted neurological real estate.

Afterwards, she cannot remember much. She woke up in a hospital bed with a nurse telling her that she had dialed 911. They had scanned her brain and referred her to a psychiatrist, who prescribed her another legion of heavyduty medications. She is stable now, cohabiting her brain with her male self, and they would be released tomorrow. She asks that I visit, so that she can tell me more. We could also hang out and mess with her EEG device.

I do not want to go. My mother would not want me visiting anyway — she thinks that Raina is narcissistic and selfish, on top of being crazy. I think about my mother, trying to plug the holes in our roof through which madness will not stop leaking, and feel sorry for her. I can hear her crying on the phone with her uncle when she thinks that nobody is listening. But my father would be happy if I visited. He says that people like Raina are special people, cutting edge people: the artists, experimenters, and expanders of consciousness. Attached to a thin rope of sanity, they spelunk the caves of madness and push what it means to be human — at risk of losing their minds.

In the end, I cannot help it. While driving to her house, I think about my father’s pilgrimage to see Peter Augustine. I, too, cannot stay away from madness, so I, too, must be mad.

Raina’s apartment is clean and modern with huge windows that let in sunlight. There are oversized stuffed animals everywhere — crabs, hearts, and lobsters. Three cats prowl across her granite kitchen counters. They stare at me with eyes like glassy blue geodes. I have seen those eyes somewhere, I think. I have seen them on Raina.

We sit on her bed and Raina curls her body around a massive toy alligator. She says that her male self is still inhabiting her brain. I ask her questions, almost compulsively, about her mind, her transition from a man, her childhood, her love life. I do not know why. I must be Freud in the body of a twentyyearold girl. Raina speaks of many things, some expected, others strange: playground bullies, splitting of her gender, abandonment by everyone who says they love her. No matter, the man in her head is her truest love of all. Sometimes he emerges and takes control over her body, although they cannot communicate. But once they learn how, they will become the strongest team. When a woman and man love each other, the woman will let the man get his way because her love is greater. She has never had sex as a man, but she might need to before completing her transition. And lastly, she says that my father is amazing and has been there for her so many times, and she is grateful.

When the conversation dies, she asks if I want to see her EEG device. She is curious about its readout whenever her male self takes control. Maybe she can learn to read the signal and communicate with him. We spend the next several hours dabbing saline solution on the electrodes, affixing them to her scalp, and tweaking the code on her computer to read the output in the right format.

Now it is time to wait. She sits in her computer chair wearing her electrode crown. The signal of the EEG oscillates on the screen. She apologizes if I’m bored and hands me me a bag of potato chips. We wait — ten minutes, twenty, thirty. She asks about the neuroscience courses I’m taking this year and offers me her vanilla vape, which I decline.

Then suddenly the left of her face goes slack and the right side goes stiff and her mouth spasms. Her eyes glaze over and lose all awareness. The EEG signal is so large and spiky that the window cannot contain it. Five, ten, fifteen seconds pass, the EEG running wild. My heartbeat is furious and I am poised to call 911. At last something snaps back into place, and Raina looks at me, blinking. I ask if she felt him. Of course, she felt him, she says, just look at the signal.

We bend over the screen. And here it is: raw quantitative data of madness. I’ve seen similar readouts for epileptics having seizures. The spikes look too random to discern a pattern, and Raina saves the file on her computer for future analysis.

It is time to go home. I give her a hug and tell her to send me her EEG data. I say goodbye to her stuffed animals and her cats that peer at me like little humans and get back into my car. On the drive back, I play the top 40 on the radio to get back in sync with the mainstream population, and sing along with Ariana Grande, who I later learn had a deranged childhood. I don’t know why, but I never tell my father about visiting Raina. I would like to think he would be proud of me, but that’s probably too much to expect, when all I did was listen to and hang out with a friend. Sometimes I also feel like I am going crazy. My brain is chaos slowly morphing into animals, but the feeling gets better when I talk to someone. I wish that Raina had an uncle to cry with on the phone. I would not return for a long time.

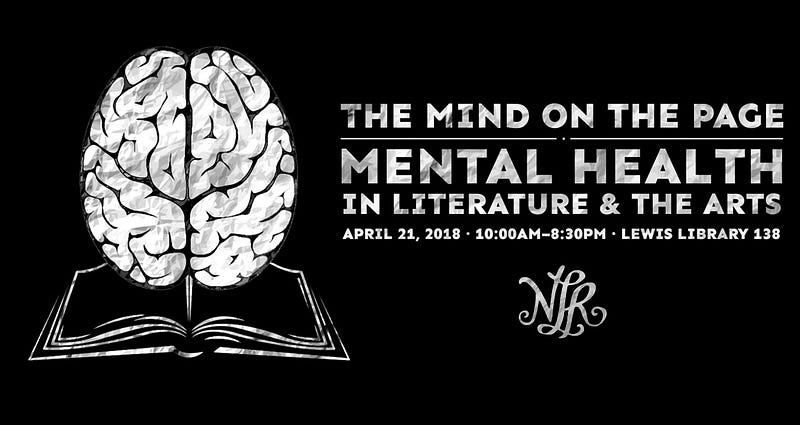

This story was the first place prose winner of the Spring 2018 “Mind on the Page” contest, judged by Angela Flournoy, a lecturer in Creative Writing at Princeton and the author of National Book Award Finalist Turner House. Flournoy will speak on the work with its author, S.M. Joseph, at Nass Lit’s “The Mind on the Page” Conference on Saturday, April 21st 2018 at 6pm.

S.M. Joseph ’19 is a junior from Boston studying computational neuroscience and creative writing. She does not like short bios because she is not easily compressible — but besides madness, she likes writing about transhumanism and religion.