SCREEN CAPSULE: Human Production in Plastic Bag (2009) and Grizzly Man (2005)

By Guest Contributor Serena Alagappan ’20

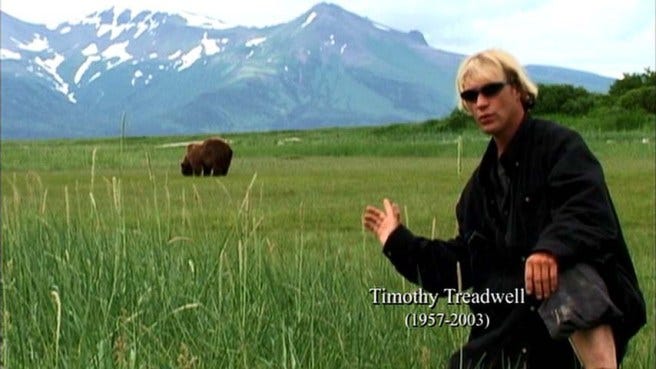

In Ramin Bahrani’s 2009 film Plastic Bag, narrated by Werner Herzog, and Herzog’s 2005 film Grizzly Man, the boundaries between humanity and the natural environment blur. Plastic is a pollutant, a toxic man-made product, that endangers other animals on land and sea. Yet, the plastic bag in Bahrani’s short film is anthropomorphized, afforded feelings, hopes, dreams, and experiences of solitude, existential doubt, and love. As an inanimate object, the plastic bag acquires humanity, and thus elicits sympathy from viewers. Timothy Treadwell, the subject of Grizzly Man, also complicates the normal lines drawn between human civilization and the wild kingdom. Breaking the laws of national parks in Alaska (which require visitors to maintain one hundred yards from bears), Treadwell camps on grizzly ground, touches the bears, talks to them, and documents them. Both films also contemplate death. In Plastic Bag, time becomes amorphous and immeasurable, so that millennia could have passed by the film’s last line, when the plastic bag says, over an upturn of melancholic chords and moving music: “I wish you had created me so that I could die.” (00:16:00) The plastic bag’s journey is largely constrained within a familiar framework of human imagination: what would it mean to live forever? Ultimately, Grizzly Man, too, is concerned with questions of mortality. After all, despite years of surviving close contact with the bears, Timothy Treadwell is mauled to death, and eaten.

Through the medium of film, Herzog memorializes two kinds of human production: waste (the plastic bag) and art (Treadwell’s footage). Herzog’s words in Plastic Bag, and Bahrani’s film at large, are perhaps correctional gestures. The film is about the indestructible human invention of plastic. But scenes that depict the plastic bag floating and curling in the wind, catching on a branch, bending as though it has a body, meeting other bags, and scenes that include the plastic bag’s reflections, replete with humor, hurdles, and heartbreak, propose beauty in something that would otherwise be simply poisonous. The plastic bag is no longer just a contaminant. Allowing and asking people to empathize with the plight of the plastic bag makes the human production of the film somehow redemptive and reforming. Similarly, in Grizzly Man, Herzog rescues meaning from Treadwell’s life and death, by drawing attention to his identity as a film-maker and artist. In the presentations of both films, Herzog makes the implicit argument that the only human productions that deserve immortality have aesthetic value. Of course, “aesthetic value” is a subjective trait, but I will focus on moments when the subjects of the films (the plastic bag and Treadwell) dwell on beauty in the natural world, and on moments when they imbue human sentiments (like purpose, faith, and love) into non-human objects. These are the aspects of the stories that, at least for Herzog, make them worth immortalizing through film.

In Plastic Bag, reflections on beauty govern much of the bag’s thoughts. In her book Forgotten Dreams: Revisiting Romanticism in the Cinema of Werner Herzog, Laurie Johnson describes how “the bag spends much of its eternal time contemplating beauty. For the immortal bag, aesthetic has the highest cognitive value. The aesthetic is what remains, (in addition to the bag itself)” (214). The film’s opening establishes its aesthetic standard. The bag tumbles across a sandy shore, as small, stuttering waves pull against the pebbles, in a burnt and diminishing daylight. There is a close-up of the water, and then of the bag, and Herzog articulates the bag’s thoughts: “They told me it’s out there. The Pacific Vortex. Paradise. You may be thinking, hey shut up and enjoy the sunset you idiot. Well, I don’t care what you think. No one needs me here anymore. Not even my Maker” (00:00:45). Here, we see both elements of the story at work, elements that, for Herzog, deserve eternal preservation. First, the beauty. It is easy for a viewer in this introduction to marvel at the infinitesimally small grains of beach, at the purring of the sea, at the light melting away. The bag does acknowledge the beauty, but he also defends his commitment to a deeper search for meaning. Second, there is the investment of human sentiments into the bag: longing for some unencumbered existence (“The Pacific Vortex. Paradise”), assertion of one’s independent mind (“Well, I don’t care what you think”), the absence of purpose (“No one needs me here anymore,”) and doubt in any intelligent design or faith-based creator (“Not even my Maker”).

Beauty remains a significant part of the bag’s reflections. When after an unknown period of isolated wandering, he encounters a red plastic bag, the two seem to dance through the wind, as their plastic bodies finally fold and fall, gently, like feathers, onto each other. They seem to embrace so deliberately in the video clip, and Herzog’s narration returns with, “wasn’t she beautiful?” (00:10:26) This is a remedial action by Bahrani. Now not one, but two plastic bags, two products that are not bio-degradable and thus threaten our natural environment, are instilled with aesthetic merit. This preoccupation with beauty is echoed later, when the plastic bag is in the Pacific Ocean, encountering new marine creatures. As he glides through the currents of the water, after freeing himself from the massive trash pit in the sea, he says, “Over time, I came to like these monsters” (00:15:54). At the utterance of that line, the camera zooms in on one fish’s face as it approaches the bag, nurturing its curiosity and perhaps imperiling its own life. At this advance, the plastic bag asks rhetorically, “Isn’t that one beautiful?”

The commitment to and the memorializing of beauty are also germane threads in Grizzly Man. Timothy Treadwell is always in wonder at the natural landscape before him. For example, at one point, he focuses his lens on a bee on a flower’s frail stem. The bee, according to Treadwell, “expired” during this encounter, and Treadwell’s voice rises in pitch and urgency when he says, “it’s beautiful, it’s sad it’s tragic” (01:08:00). Similarly, when he comes across one of his favorite female bear’s feces, he gently pats it and says affectionately, “everything about her is perfect,” admiring that it is “still warm.” How marvelous it is, he excitedly proclaims, that this was “just inside her” (01:09:00). In this scene, Treadwell restores beauty to waste itself, to the animal’s excrement, something many would see as disgusting. In yet another instance of Treadwell emphasizing the aesthetic value the environment carries, he underscores the appearance of the fox he is “friends” with. He implores his viewer to recognize “this beautiful fox,” and says, “People are trying to kill him for his gorgeous fur. We want this to end. This beautiful fox and me, we ask the public to stop killing and hurting these foxes. If they knew how beautiful he was, they’d never hurt him” (00:37:00). Ironically, of course, this is precisely why poachers hunt foxes, as their customers find the fur attractive. Nonetheless, Treadwell appeals to the human appreciation of beauty in his effort to preserve the wild species of Alaska.

In a discussion of aesthetics in Grizzly Man, it is vital to include the moment when Herzog himself intervenes with a cinematic analysis of Treadwell’s footage. He explains how Treadwell, “as a filmmaker, was methodical…often doing up to fifteen takes” (00:38:30). In so doing, Herzog justifies the immortalizing of Treadwell through the integrity and value of his artistic material. While vegetation on the side of a sloping ground swells in a gentle gust, Herzog declares: “Treadwell probably didn’t realize that seemingly empty moments had a strange, secret beauty. Sometimes images themselves developed their own life, their own mysterious stardom” (00:40:10). Interestingly, Treadwell is in most of the frames that he produces, so while he does seek to portray the animals and their environment, he is also, the not-so-mysterious star of his own recordings. In certain takes, he obsesses over how he looks, taping the same scene over and over, trying the same lines with bandanas of different colors (00:39:20). The aesthetic value of his footage was undeniably something Treadwell cared about (in the animals, the nature, and himself), as well as the element of his life that Herzog chooses to focus on: Treadwell not as bear whisperer, or fate-tempter, but Treadwell as filmmaker.

Besides explicit contemplations on beauty, both films acquire aesthetic significance by personifying non-human objects (by making intelligible and therefore admirable, the existence of a bag or a bear). Both films contain reflections on “purpose.” In Plastic Bag, much of the film is dictated by the bag’s crippling and sorrowful reminiscence of the life phase when he had purpose: when he was with his Maker. There is some humor in the scenes of the plastic bag and his Maker (the woman who pulled him out of a grocery store check-out line). He describes feeling close to his Maker, the intimacy of being “skin to skin,” when she fills the bag with ice for a sore ankle and holds it against her foot (00:03:15). Another mildly comedic scene is when he says, he would do “anything for her,” during a shot of her using the bag to pick up her dog’s droppings (00:03:57). But when he is thrown out, he despairs, for he no longer has a purpose. He wonders what the meaning of his life is. He imagines his Maker bereft, thinking, “where is he? where is he?” And he reckons his purpose is to be reunited with her. By the film’s end, he is filled with doubt: “Did my Maker exist or had I created her in my mind? Why were my moments of joy so brief?” (00:15:45) His moments of joy were defined by purpose. This is, of course, a human sentiment — to expect and demand meaning beyond survival. But we are struck with the jarring realization that the plastic bag’s life is utterly inhuman when the final seconds of the film deliver the punch: “And yet like a fool, I still have hope I will meet her again. And if I do, I will tell her just one thing. I wish you had created me so that I could die” (00:16:00). His purpose is both relatable and utterly foreign; our empathy is drawn out but then inexplicably stunted. Even if we relate to a quest for purpose, how could we understand the infinite waiting and madness wrought by immortality? This is the surprise, sadness, and success of the film: both the humanizing of the plastic bag and the subsequent imagination of what is totally non-human.

In Grizzly Man, Treadwell believes his purpose is to stop poachers, and preserve the bears, wildlife, and natural landscape of Alaska. Yet, bear biologist Larry Van Daele explains how poaching is not even a primary concern for the species on the island where Treadwell documented the grizzlies (01:17:15). Furthermore, when Herzog presses Dr. Sven Haakanson, the Alutiiq museum curator, whose family and community had been in Alaska for millennia, he responds:

It’s tragic because, yeah, he died…and his girlfriend died. You know he tried to be a bear. And for those of us on the island, you don’t do that. You don’t invade on their territory…for him to act like a bear the way he did would be…I don’t know…to me it was the ultimate disrespecting [of] the bear and what the bear represents (00:29:15).

Herzog respectfully asks, “but he tried to the protect the bear, didn’t he?” And Haakanson responds, unconvinced, “I think he did more damage to the bear.” He goes on to explain that Treadwell “habituated” the bears to human beings:

Where I grew up, we avoid the bears and the bears avoid us. If I look at it from my culture, Timothy Treadwell crossed a boundary that we have lived with for 7,000 years. It’s an unspoken boundary. But when we know we’ve crossed it, we pay the price.

What does it mean if Treadwell’s “purpose” is undermined by this testimony? Herzog salvages meaning for Treadwell when he says that “the argument of how wrong or how right he was…disappears into a fog” (01:39:50).

“What remains,” Herzog insists, “is his footage.” He continues:

And while we watch the animals in their joys of being, in their grace and ferociousness, the thought becomes more and more clear: that it is not so much a look at wild nature as it is a look into ourselves, our nature, and that, for me, beyond his mission, gives meaning to his life, and to his death.

Again, Herzog prioritizes the aesthetic (documentation of the animals), and the human (the self-referential quality of this film in general, the window into our own human nature). Not only are many animals personified, (Treadwell names the bears, Downey, Tabitha, and Melissa, and makes the fox his namesake, Timmy the Fox), but the story of Treadwell itself is also humanized by Herzog for its aesthetic value as a film.

Besides humanizing Treadwell and the plastic bag by underscoring their respective “missions” or quests for “purpose,” both subjects also embody the human desire for love. This thread makes the films relatable and beautiful, and for Herzog, worthy of immortalizing. In Grizzly Man, standing on the edge of a riverbank, Treadwell repeats three times, “I’m in love with my animal friends” (01:27:20). Later in the film, two of his friends who loved him deeply, spread his ashes in the Grizzly Maze, and one of the women says with a smile, “he finally figured a way out to live here forever” (01:30:00). She offers an affectionate, sentimental, (if dangerously Romantic) way of viewing Treadwell’s gruesome death. Yet, what she says is true, not only in where the remains of his physical body rest, but also in the imaginative space where other human beings will recall and commemorate him (thanks to Herzog’s film). There are also various scenes in which Timothy contemplates his troubles with love, how he struggles to understand women and the relationships of his past. As Herzog puts it, “facing the camera” for Treadwell began to take on “the quality of a confessional” (00:40:40).

Similarly, Plastic Bag presents several love stories. There is the brief affair with the red plastic bag, the fleeting obsession with the Vortex, and the enduring love for the Maker. The plastic bag is achingly desperate to be rejoined with the one who gave him purpose. The plastic bag’s quest for his creator has numerous symbolic implications. It could be a metaphor for a typical devotion narrative, a Biblical one, perhaps: the struggle to honor and return to God’s perfection in a postlapsarian world. It could be a metaphor for the God-complex of human beings as we narcissistically evaluate our shared, natural environment. It could be a metaphor for interpersonal love, plain and simple, for missing someone who has abandoned you. After waiting so long that the waiting “drove him mad,” the bag encounters other plastic bags that have chained themselves to a fence, to preach about “the Vortex,” the mass of trash that is dumped into the Pacific Ocean. For the plastic bag, this is “heaven,” and those preacher bags claim “There is no Maker.” The plastic bag seems to finally give up on his Maker and concedes, “I went searching for the Vortex. Some ate pieces of me until they realized I was useless to them. I wonder where those little pieces are now.” This is a human fear, that we may be used, that parts of us are swallowed, deserted, or forgotten by others, who rush past us, gleaning what they desire from us as they go.

Despite these lost pieces of himself, the plastic bag does finally make it to the Vortex. And the irony of the Vortex is rich. The plastic bag marvels that he is finally with his own kind, that “they covered the area of a small continent.” This paradise for trash, produced by human beings, is being corrected, in a sense, by Bahrani and Herzog, into something beautiful, even if it is an untidy beauty. The miracle of aestheticizing this spinning mass of garbage is jagged, but it is still effective. Viewers of Plastic Bag know how harmful this human production of waste is to the environment, yet when the plastic bag first arrives at the Vortex he is joyful, and enamored of this place: “I loved going in circles and circles and circles.” It is hard not to feel at least a modicum of happiness for him after all that waiting, seclusion, and searching. But after some time, he admits that “no one…thought about anything,” and he confesses, “I grew restless, and I started to think about her again. So, I spun around so fast that I was free. But I was quickly trapped. I have no idea how long ago that was.” Ultimately, the plastic bag’s faith in the Vortex is thwarted, but his faith in his Maker affirmed. Nonetheless, doubt colors and coexists with his faith (“Did my Maker exist or had I created her in my mind?”) (00:15:45).

This seemingly incongruous, but altogether necessary combination of doubt and faith is echoed in Grizzly Man. At first Treadwell claims, that he never believed in God. But when he anguishes over the drought that is forcing the animals to starve and die, he begins to scream into his camera, “I’m not a religious guy,” but “if there’s a God, DOWNEY NEEDS TO EAT.” He is shouting to the roof of his tent when he exclaims, “I want rain! If there’s a god…let’s have some WATER, Jesus boy or Christ man or Allah or Hindu floaty thing, let’s have some fucking WATER for these ANIMALS!” Within a few hours, (a time-lapse of only several seconds in the film), Treadwell says, “It’s raining. I am the lord’s humble servant…there has been a miracle here. We have over two inches now and it is not stopping” (01:12:51). The conception of God is a human one, as are religious convictions. So again, this nuanced display of “human nature,” for Herzog, justifies the immortalizing of Treadwell. The footage is a meaningful portrait of humanity, which in the logic of storytelling, achieves aesthetic success, and therefore warrants memorializing.

At first blush, Herzog and Bahrani are, in these cinematic productions, leveling critiques against human intervention with, and destruction of the planet. Both demonstrate the pain wrought from neglecting the boundaries that should be respected between humans and nature. The plastic bag lives a mournful life, wishing that it could be destroyed, and Timothy Treadwell (and his girlfriend Amy Huguenard) die at the hands of the creatures he loved so much. Herzog’s choice to open the film with Treadwell proclaiming “I will not die at their claws and paws. I will fight…I will be one of them. I will be master” feels hauntingly sarcastic (00:02:09). It also suggests that Herzog is deliberately emphasizing the hubris and insanity of Treadwell, but as we know from Herzog’s editorializing, and as we can infer from Herzog’s choice to make this film at all, he believes Treadwell’s story has value. Plastic Bag and Grizzly Man are beautiful films that probe the precarious intersection between human beings and the natural environment. Both are replete with thought-provoking considerations of love, faith, and purpose. But these films are themselves human products, imbued with self-referential, human qualities, and immortalized by their medium. In their commitment to aesthetic visions, they run the risk of obscuring the things they are ostensibly trying to raise awareness for and protect: animals, natural habitats, the environment. On October 6, 2003, two human beings died in Katmai National Park, but later, the grizzly bear who ate them was also killed. (Herzog interviews someone in the film who explicitly says Treadwell would never have wanted a bear to be killed.) That grizzly bear was one of many wild animals who had been habituated to human beings by Treadwell. In the solicitation of human empathy for a plastic bag, an inanimate object, we might forget that it is that plastic, that is killing animals on the earth and in the ocean. Perhaps this is the ultimate, ironic, and jarring question that the films, together, pose: What does it mean for a viewer to be left empathizing only with Treadwell, and not the bear, with the plastic bag and not the fish who ate a piece of it?

Bibliography

Bahrani, Ramin. Jenni Jenkins, Werner Herzog, Barbara Weetman. Plastic Bag, 2009.

Herzog, Werner. Erik Nelson, Jewel Palovak, Timothy Treadwell, Amie Huguenard, Franc G. Fallico, Peter Zeitlinger, Joe Bini, and Richard Thompson. Grizzly Man, 2005.

Johnson, Laurie Ruth. Forgotten Dreams: Revisiting Romanticism in the Cinema of Werner Herzog. NED — New edition ed., Boydell and Brewer, 2016. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt18kr6wj.

Serena Alagappan ’20 is a junior from New York City studying comparative literature and creative writing. She loves Murray Dodge cookies and caffeine. On the cover page of her second grade diary she listed her dreams: 1) Get a pet giraffe. 2) Read every book in the world. 3) Become a writer. Her dreams haven’t changed much since!

SCREEN CAPSULE is a film/TV review project of Bes Arnaout, in which she attempts to help mainstream critical consumption of the moving image through non-academic criticism of the formal techniques and the thematic content of all screen-media.

Bes can be reached at bes.arnaout@princeton.edu