What We’re Loving: New Staff Edition 2020

Since the beginning of the spring lockdown, one of my favorite musicians has pushed out a generous number of songs: an album in early summer, followed by several stand-alone tracks. Casey Luong, known by his stage name Keshi, independently writes, sings, and produces his music. This fluid process enables the full expression of his artistic style and melodic quirks — most notably high falsettos at the bridge and intro, an underlying melancholic element to his lyrics and melodies, and other such elements.

Of these new releases, I particularly enjoyed the song “Always.” The premiere version was written with tinkling instruments, chords, and lofi voice-overs, and the second iteration, which was his first draft, resembled the ballad, adagio-tempo form of most of his repertoire. Both versions share the same lyrics and melody, but depart on their selection of instruments. They address the aftermath of broken relationships in different ways. The first, in particular, offers a perspective that disrupts the binary of typical pop songs — the antipodes of Adele’s heartsick “Someone Like You” and Ariana Grande’s blithe “thank you next.” Rather, it tackles the instant disbelief experienced when something good, seemingly “always,” has ended. Luong’s song is not dominated by jeremiads; with only two verses and a chorus reiterated, it is indeed one of his simplest pieces. But realness and spontaneity emerge from that basic construction — from the fact that he could have seized these lyrics and drawn them out as one continuous stream of consciousness.

Yet the main inspiration of this song, I believe, comes from the instrumentals — a lighthearted ensemble of keyboard, guitar, bells, turntable scratching, and so on — which seem to clash with the emotional subtext of the song. An oxymoron of happy-sad, or another shade of either emotion. An intermediary stage of recovery. The contrast of this iteration with the second ballad-style piece, moreover, allows for deeper appreciation of both songs. It provides an object lesson of instrumentals — a departure from the common emphasis on lyrics and melody — that even with all else held equal, the quality of instruments can totally change the meaning of a song. For anyone who is interested in music composition or who wants to add new energy to their Spotify playlist, “Always” by Keshi is a song you should definitely check out.

— Bryan Wang ’24

During the summer months of quarantine, I embarked on a pretty serious Netflix binge, particularly in the genres of foreign-language film and animation. One movie that popped up on my recommended list, which actually happened to tick both boxes, was the 2019 French animated drama fantasy J’ai perdu mon corps, known in English as I lost my body. Directed by Jérémy Clapin and animated by Xilam Animation, J’ai perdu mon corps is a Cannes Nespresso Grand Prize-winning and Academy Award-nominated film based on the novel Happy Hand by Guillaume Laurant, who is also known for the screenplay of French romantic comedy Amélie.

Centered around a young man named Naoufel (or perhaps more accurately, both him and his hand), the movie leads us through two intertwined storylines: one told in flashbacks of the orphaned Naoufel struggling to adapt after the sudden death of his parents, and the other set in the present of a severed hand making its way through Parisian suburbs in hopes of reuniting with its body. Through the unfolding of the dual narratives, we slowly come to learn more about Naoufel’s history, from his happy childhood in Morocco to his subsequent relocation to France to live with his negligent uncle and cousin, as well as the circumstances of his involuntary amputation. As both plots begin to converge, the film leaves us with an understated yet poignant commentary on the themes of tragedy, loss, and reshaping one’s fate.

In addition to its uniquely creative screenplay, J’ai perdu mon corps is distinguished by its beautiful animation and extraordinary score — the latter of which has been recognized by the 2020 César Award for Best Original Music. The animation style is simple yet attentive to detail, using nuances in color and tone to evoke different moods throughout each scene. Coupled with Dan Levy’s powerful score — which blends traditional instrumentals with contemporary synths to create rich, swelling melodies — the movie has a constant sensation of restlessness and urgency, propelling the action of the piece forward. The eponymous title track embodies this feeling of perpetual motion perfectly, as it begins with a repeated quarter note electronic refrain that gradually builds in layers of strings before it crescendos to a climax. Working in skillful harmony, the animation and the score together serve to set the rhythm of the film as it moves swiftly onward — effectively mirroring its central subject matter of forward movement and the relentless passage of time.

— Megan Pan ’22

As of late, I’ve been loving Everyday Life, Coldplay’s quirky eighth studio album. I’ve grown up on Coldplay; they’ve somehow magically produced a soundtrack for every part of my childhood in each of their albums. Everyday Life was the first album that they released after my childhood, when I started getting into contemplative and creative writing again, as if they knew.

One of the reasons this is my favorite album to write to is that the music is instrumental-heavy. For example, the drumbeat of “Arabesque” is perfect for inspiring a continuous stream of creativity and insight. There are lyrics to the song, but they’re muted in such a way that it’s not distracting to your writing process — it’s like the lyrics are another instrument adding to the ensemble. I’m the kind of girl who likes to listen to classical music or nature sounds to concentrate, and this album marries these two perfectly, in conjunction with spoken-word poetry and those classic Coldplay guitar solos. The song “بنی آدم,” which translates to Children of Adam, is a perfect example of this, beginning with a beautiful piano instrumental that flows into a guitar solo, with spoken Arabic and Nigerian poetry overlaying the music. It makes you feel as though you’re 30,000 feet up in the sky, looking down on the world with a spirit of adventure that inspires the best writing. If I ever need some writing inspiration, you can trust that I will turn to this album.

— Saareen Junaid ’23

Bojack Horseman follows the life of an alcoholic, self-loathing, offensive, washed-up sitcom actor struggling to make a comeback in the changing landscape of Hollywood and the world. He’s also an anthropomorphic horse.

While Bojack’s taxonomy and bipedalism may be off-putting, his cynicism and insecurity are reflective of something every viewer is familiar with. He’s a character that’s meant to be hated, but he’s also every bit as frightened and lost as everyone else. He’s an embodiment of all of the things we don’t like about ourselves and forces us to come to terms with many of our own anxieties and misgivings as we follow his journey.

Animation is a medium so regularly associated with children’s shows and movies that it’s often hard to watch animated shows without bias. But Bojack Horseman uses animation as a means to explore even darker themes and stretch the boundaries of audience engagement. The show relies on the medium to keep viewers just detached enough so that they aren’t devastated when their favorite character relapses or overdoses. It also allows the creators of the show to tackle human issues in an entertaining and uniquely thought-provoking way.

Bojack Horseman manages to balance comic relief and animal puns with meditations on everything from social issues to the fear of death. It’s ridiculous and beautiful and terrifying and devastating, and it will make you question your life and all of the decisions you’ve ever made.

Stream it now on Netflix.

— Conner Kim ’23

I don’t usually listen to music for the lyrics, as I appreciate a song’s ambiance, instrumentals, and overall head-bop-ability much more. Penelope Scott’s new album, Public Void — which pairs intimate lyricism with harsh, glitchy instrumentals — is an exception to this rule.

I was in a bit of a musical drought when I discovered Scott’s new album, so naturally, I have listened to it about 20 times in the past three days (a manageable task, considering the whole thing is only 26 minutes long). I had already fallen in love with her most popular song, “Sweet Hibiscus Tea,” and its poignant, heart-rending lyrics a few months prior. While Public Void’s tone is much more bitter and vengeful, it maintains the same tenderness and honesty as her previous work.

One of my favorite things about the album is the way Scott portrays womanhood. “Cigarette Ahegao,” for instance, subtly comments on the way women are hyper-sexualized in today’s media and how we in turn learn to do the same to ourselves as a coping mechanism. “Lotta True Crime” is also a great feminist hype song, and perfect for getting in the Halloween spirit. Some of my other favorite tracks are “Feel Better,” which perfectly captures the turmoil of a painful breakup, as well as “American Healthcare (Glitzy)” and “Rät,” which touch on the detriments of modern capitalism.

So if you’re looking for the perfect album to channel all of your current angst, dread, and cynicism, look no further than Public Void!

— Eva Vesely ’24

When I sit down at my desk and need to be productive, I often turn on my go-to instrumental jazz pop (Spotify’s This is Jazzinuf playlist) or high-energy songs with driving beats, like Gnarls Barkley’s “Crazy” and MGMT’s “Electric Feel.” But hours later, as my legs grow stiffer, my room stuffier, and my manner increasingly standoffish, I need to hear some words of encouragement. In the same way a person feeling unrequited love can’t spend all their time mourning and might turn to sad love songs, I’ve found a song that can help me feel and deal with fatigue. Crumb’s “So Tired” is that savior.

The chorus feels like it could be a diary entry by myself or any other tired student who feels like they’re running an ever-lengthening race in the late hours of the night: “Chasing the daylight I’m riding the train / Trying to stop but this feeling remains.” However, Crumb does not allow us to wallow in this feeling after the first chorus. The second verse’s syncopated rhythm and increase in tempo evokes the sounds of that train we’re riding, and focuses the listener on the journey rather than the uncertain destination.

Again, it only lasts so long before we return to the tired chorus. This song is cyclical. Often in our day-to-day life, we can’t completely recover from tiredness. We just alternate between feeling and suppressing it. We can try to escape it once we think we’ve reached our destination, but whether or not this is how we should approach late nights is another issue. It’s just how it is for most of us.

But again, after the tired chorus, we bounce back. A crescendo and focus on instrumentals running past the end of the chorus signifies the listener following the speaker’s mother’s advice: “So get into the game she said, resist the pain don’t go insane.” At the end of the piece comes the encouragement to keep going — even if I’m tired, even if the feeling remains.

— Mollika Singh ’24

Because I am a person of obsessions, and because I impose my obsessions upon those who come near me, I have read Brian Doyle’s “Joyas Voladoras” aloud many times — to friends, students I tutored over the summer, and my mother this morning in the kitchen. Why thrust more of myself toward others when I can share Doyle’s words, which effortlessly articulate how I aspire to interact with the world? And so, the essay has become a sort of adopted manifesto.

“Joyas Voladoras” is succinct and dynamic, universal and intimate. The essay begins with the hummingbird, celebrating its dexterity, color, and ferocious energy for life. With humility and childlike fascination, Doyle moves from the hummingbird to the blue whale, eventually broadening his scope to all living things. He examines the heart — its solitude, desire, and tenacity — and how it holds our human tendencies. The final sentence, an elegiac list of sensory images like “a child’s apple breath” and “the words ‘I have something to tell you,’” throbs with longing and nostalgia. “Joyas Voladoras” invites us to consider how we interact with the living world, and at the heart of that, how we interact with other humans. How wondrous it is to be able to remember — and to have a language for remembrance.

I think literature should be a lunge toward the truth. Perhaps the truest form of experiencing Doyle’s essay came this past summer, in the dim middle-of-the-night stillness of an Airbnb. A friend and I sank into the living room sofa, close enough to hear each other’s pulse. It was a fragile, emotional moment, and I was careful to half-speak, half-whisper Doyle’s words. The way my voice, aware of itself, walked between smallness and fullness felt true to the essay: “So much held in a heart in a lifetime. So much held in a heart in a day, an hour, a moment.” It’s a divine thing, for prose and life to mirror one another, to look each other in the eye. As if to say, I see you, I’m with you, and I’ll be here in the morning.

— Sabrina Kim ’24

I don’t doubt that Gabrielle Hamilton’s culinary creations are more delectable than her rich descriptions of brown-buttered bread decorated with glazed jam, or her momentous words about the last slice of mildly-sweetened chocolate coffee cake. I first read American chef, food writer, cooking-guru, and restaurant owner Gabrille Hamilton’s work in her New York Times article “My Restaurant Was My Life for 20 Years. Does the World Need It Anymore?” This piece was not one of Hamilton’s usual contributions about potatoes buried in salt or smoky eggplant smothered in pesto. This piece was not a recipe for transforming raw vegan ingredients into an unrecognizable delicacy. This piece was not an epiphany of food — a saga of how far cheese can stretch or a retelling of how crispy croquettes can be.

This piece was both about food and not about food — a brutally honest narrative of what it means to sever a relationship with food and to be in danger as a restaurant owner in the midst of a pandemic.

In this narrative, I didn’t find the usual, calm voice that I normally search for in Hamilton’s pieces. Hamilton tells us a story of struggle, despair, and hopelessness as she and her partner navigate the messy realm of obtaining loans, firing employees, and parting ways with her New York City restaurant, Prune. The restaurant is where Hamilton grows up, becomes collaborative, finds her friends, meets her husband, and discovers her passionate love for cooking.

Although Hamilton’s writing is honest to the core and matter-of-fact, her prose digs into the flesh of what it means to build and cultivate relationships — with people, food, and places. Her words are intentional and lasting: stimulating fear, compassion, and taste. She writes about food and meals, as many authors do. But what pushes Hamilton’s writing beyond the scope of expectations is her experience as a chef and restaurant owner in a city devastated by the pandemic. She dwells on food, but also spends time discussing the role of restaurants and dining out — something that was previously taken for granted.

The most memorable aspect of this piece is Hamilton’s masterly entanglement of the intimacy of food with the novelty of emptiness. Empty streets, empty dining tables, and empty chairs are an unconventional sight at Hamilton’s tight-knit, downtown NYC restaurant. These were the very streets that were bustling with regulars, the tables that were filled to the brim, and the chairs that were rearranged to make room for family dinners. Hamilton’s writing captures fear and loss by transforming food into a weapon of connection and belonging. She tugs on her appreciation of food, flavor, and intimacy to make sense of an unsettling situation and contemplates the future of Prune.

— Aditi Desai ’24

It’d be dishonest for me to describe my understanding of American Football as anything more than a vague grasp of the concept. So, I was surprised to find how much I adored a story so rooted in the sport. John Bois’s 17776 imagines a world where no one has died, aged, nor been born in about 15,000 years. I promise this is still about football. It’s something of a post-scarcity utopia, which explores what people would do if they were free from fears of death, war, poverty, and all those awful things. 17776 answers that we’d “perpetually hang.”

The people of Bois’ world spend most of their time playing absurdly long-lasting, nation-spanning games of football with increasingly ridiculous rules. The narrators are three satellites whose computers gained consciousness and are watching humanity from far above. Unsurprisingly, they’re also pretty preoccupied with football. The story looks at humans as being, fundamentally, creatures of play.

Bois’ writing weaves the grandiose questions of consciousness and meaning with less ambitious subjects like Lunchables combinatorics and “hey, wouldn’t it be sick if a quarterback ran into a tornado.” He makes the case that these dumb but fun conversations are just as meaningful as those big ones. Despite dealing with the existential troubles of machines distanced from us by eons, astronomical lengths, and immortality, the conversationally heartfelt and deeply human emotionality persists throughout.

The work spans the length of a novella and is entirely online, so if you have a few spare hours, be sure to give it a read. It’s an experimental combination of dialogue pages to be scrolled through, still images, videos, and what I’d describe as “intensely okay quality” Google Maps animations. It’s fantastic. This is the sort of story which can only exist through the internet — a stunningly creative use of the medium to form a novel take on storytelling. If you check it out — which, again, you really ought to — follow it up with Bois’ sequel 20020, which is being published throughout the month and will be finished October 23rd.

17776: https://www.sbnation.com/a/17776-football

20020: https://www.sbnation.com/secret-base/21410129/20020

— Andrew Matos ’23

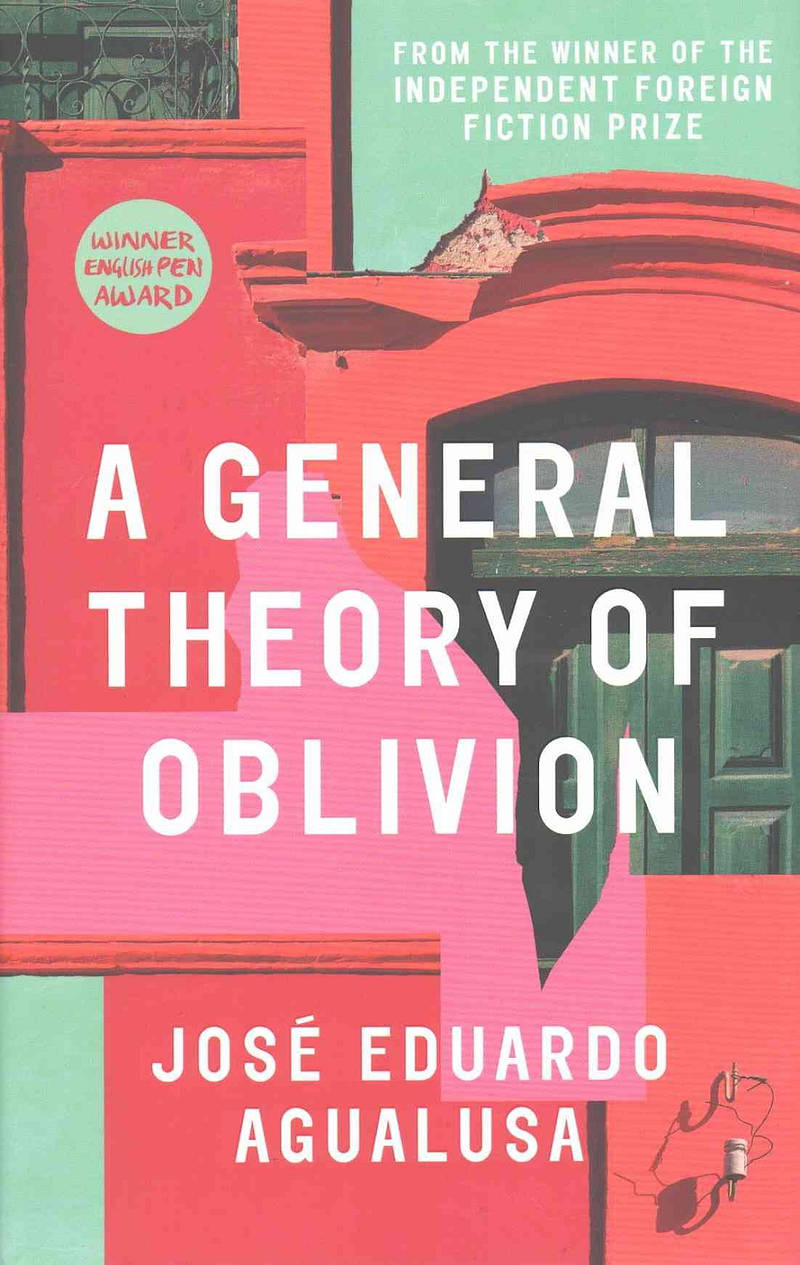

Brilliantly interwoven lives slowly untangle in José Eduardo Agualusa’s timeless masterwork. Despite its focus on only a few individuals, the novel manages to capture an entire cultural movement — thirty years in 250 pages. While the book is short enough for a Sunday afternoon read, be careful — it reads more like poetry than prose. Every word carries weight, and some chapters will make you pause and think, pause and grieve, or pause and cope.

Languages like Portugese do not get translated into English often — languages with their own unique inflections and ideas that carry voices most Americans will never hear. This translation flows smoothly in English without losing the undefinable, non-English quality that adds radiance to each word. I’m loving it.

— Ben Guzovsky ’24

On a misty summer day of 2014, splendid colors exploded in magnificence on the riverfront of the Power Station of Art in Shanghai.

The explosion event was designed as the opening to Cai Guo-Qiang’s exhibition The Ninth Wave. Cai is a renowned contemporary artist who focuses on gunpowder and explosion art from Quanzhou, China. The main installation of the exhibition, named eponymously as The Ninth Wave, is in the form of a wooden boat that incorporates 99 life-sized replicas of animals, which seemed to be clinging onto the boat as though it were their last hope of survival.

The name of the exhibition, The Ninth Wave, refers to a painting of the same title by the Russian artist Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky, and is an old sailing expression referring to a wave of incredible size that comes after a succession of incrementally larger waves. In Cai’s exhibition, a wave of formidable force and irrevocable destruction is a characterization of the severity and alerting state of global environmental issues. Thus, the wooden boat — and the exhibition as a whole — is, in a sense, a projection of the present and future in the form of an ark in Fujian style — the remaining harbor for us in face of relentless devastation.

In this blurb, I will focus on the explosion event, which is available in video forms online which you can use to get a better sense of the touching and awe-inspiring aspects of the event. If interested, you can also check out the amazing Netflix documentary Sky Ladder, which features an overview of the best works of Cai’s career. Now, let’s get down to the point…

The 8-minute long explosion event is arranged in three chapters: “Elegy”, “Remembrance”, and “Consolation”.

As the fireworks explode above the river, colorful smoke diffuses into transient paintings that contrast with the lowly saturated steel blue of the city. The explosions were evolving processes. As new explosions occur and the smoke of past ones float away, the visual landscape reshapes itself. There is an impression of ethereality — the landscape formed resembles our depiction of outer space, with clusters of star clouds. (For the record, the explosion event used biodegradable colored powders to minimize pollution). Cai explains that he wishes to use this contrast — which illustrates the conflicting relationship between humans and nature — to create a deep sense of melancholy. This explosion event took place on the Huangpu River and was open to viewing for everyone at the scene, initiating a public conversation among the viewers and a conversation between the artist and nature. It is unique because it compels you to contemplate its meanings and implications; it is deeply moving and alerting beyond one’s imagination. The fact that it is astonishingly beautiful does not suffice for an accounting of the emotional effect it has on its viewers. Perhaps this effect is due to how such beautiful art remained on earth for mere minutes.

— Briony Zhao ’24

As a K-drama fan, I always take what I see on-screen with a grain of salt. K-dramas are notorious for their cliches and idealization of life in Korea, but Skycastle is one of the few kdramas to date that delivers a more relevant story. If you’re tired of rom-coms, you won’t regret giving Skycastle a try.

Skycastle centers on four families from an elite area in Seoul who are obsessed with getting their children into Korea’s top universities — no matter what it takes. Absorbed in a world of privilege, wealth, and conformity, they are made pitiful to viewers by their narrow-mindedness and snobbery. They eventually enlist the help of a highly esteemed but suspicious tutor, under whose brainwashing future medical student Kang Ye-seo descends into a depth more sinister, ready to cut ties with her mother and to take academic competition to a murderous level.

Admittedly, Skycastle falls prey to over-acting; however, I’m glad I stuck with it because it mellows out after the first few episodes. Despite being a satire (and therefore exaggerated), its story is nothing new: suicides and murders triggered by academic pressure happen every year. Of course, academic pressure doesn’t need to manifest so extremely: this drama rings uncomfortably true for students like ourselves who can get too caught up in comparison, competition, and stress. It’s a powerful reminder to step back from our bubble — to reevaluate our definition of success, and what we are sacrificing for it.

— Fizzah Arshad ’24

I have a Spotify playlist of 1331 songs totaling up to 73 hours of music.

I scrambled my playlist and rediscovered this random place on the internet: “THIS MAN FLEW TO JAPAN TO SING ABBA IN A BIG COLD RIVER — Austin Weber — Mamma Mia Official Video.”

This music transports the listener to those places on the internet that bring unexplainable joy. Not only does the original video feature daily life in the Kamo river in Japan, but it also has the same live-recorded audio in both tracks.

All in all, Mamma Mia by Austin Weber provides three minutes and thirty seconds of euphoric joy. I highly recommend that you listen: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kewXtkGmDtw&ab_channel=AustinWeber.

— Kathy Li ’24

If you have 38 minutes and 47 seconds to spare, give Wallows’ first studio album Nothing Happens a listen. This indie-rock piece is an ode to the pains of growing up — a resounding theme for college students searching for a place and an identity as they transition from adolescent to adult. One of the things I love about Nothing Happens is how thematically sound the album feels from start to finish: with each song you feel the push and pull of youth and adulthood.

My favorite song off the album switches frequently, but, as of right now, “Treacherous Doctor” stands on top. While musically upbeat, the song contains lyrics verging on an existential crisis. Rather than detracting from the song’s meaning, the contrast emphasizes it by inviting listeners to release their inhibitions and enjoy the ride.

As the final track comes around, the album ultimately reaches its final conclusion that yes — nothing happens. On face this sounds somewhat nihilistic, but Wallows is trying to remind its listeners that there is more to life than the struggles of adolescence.

— Katie Rohrbaugh ’24

As midterms stress starts to flood my weekly schedule, The Neighbourhood’s brand new, conveniently-timed album manages to provide a perfect escape into a moody, alternative, space- cowboy wonderland. Coalescing the band’s usual low-tempo sound with bright bursts of modern R&B and techno, Chip Chrome and the Monotones brings to life a perfect balance of past and present. Written as a Ziggy Stardust-inspired concept album, it tells the story of “Chip Chrome”, lead-singer Jesse Rutherford’s silver-painted alter ego, and invites audiences to explore the character’s every thought and emotion.

Perhaps my favorite thing about the album is how it manages to transport its listeners into the middle of a limit-defying, sci-fi-esque 70’s film. With Chrome as the main character, we explore an alternate dimension that ties up everything from melancholy to excitement in concept-appropriate, holographic string. The first song — a short, instrumental piece unsurprisingly titled “Chip Chrome” — makes us feel as if we’re traveling through time and taking our place beside the album’s eccentric protagonist. We then progressively come to know and sympathize with Chrome as we make our way through the rest of the pieces. With each song, we assimilate his existentialist battles against unrequited love and self-aversion, all while hopping from love ballads, to folk anthems, to moody rock. Perhaps my favorite, “Middle of Somewhere” concludes the album by elucidating the dissatisfaction we feel when life starts becoming increasingly unexpected. As a college student unwillingly doing school from home, I feel a tragic — yet undeniable — chord struck in me by Rutherford’s emotive lyricism. For anyone else interested in taking a journey beyond the confines of their pandemic-centric world, The Neighbourhood’s interspatial and reflective take on their usual alternative sound is a definite (and highly praised) must.

— Mariana Bravo ’24

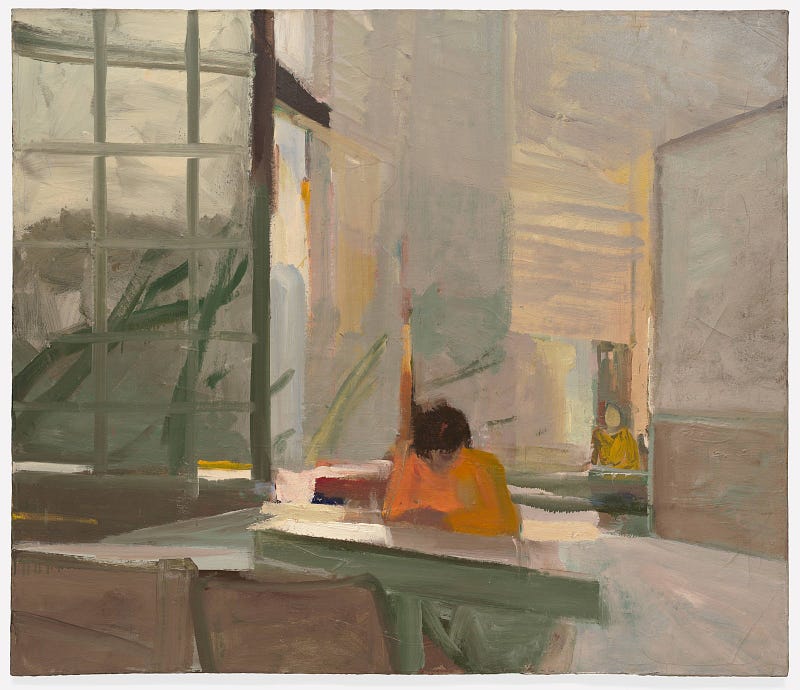

Every single day of my junior year of high school, I looked at Elmer Bischoff’s painting, “Orange Sweater” (1955). It served as the background for my phone’s home screen, and even though I looked at it frequently, I never gave much thought to why I liked the painting. It was impulsivity — I just knew that I enjoyed looking at it. Over the past month, while idyllically scrolling through my Pinterest feed, trying to find inspiration for my next art piece, I stumbled across Bischoff’s work again.

Bischoff’s painting depicts a figure clothed in orange, studying in a yellow- and green-toned library. The painting elicits a sense of calmness, and one can feel the serenity which diffuses from it. This painting represents what I long for: I would give so much to be able to study in a library — or even inside of a public building! — right now.

It’s those moments of peace and quiet that I now crave amidst this time of politics, sickness, and social upheaval. This painting offers me solace, and it soothes me with its comforting brush strokes and tones.

— Natali Kim ’24

In a summer that for me was defined by both stifling claustrophobia and empty loneliness, I quickly fell in love with Noah Kahan’s EP, Cape Elizabeth. Fully acoustic, with only Kahan’s guitar as accompaniment, the collection of folk songs is fully stripped down and deeply intimate, both in its production and in the vulnerability of Kahan’s lyrics, which at times are so emotionally honest that I felt closer to him than I have to friends in real life. Through masterful storytelling and almost effortless musical prowess, Kahan explores themes of loss, emotional isolation, companionship, and escape.

The title of the EP refers to a small town in Maine that Kahan, at the time of writing this album, had ironically never been to. He sets Cape Elizabeth as the backdrop of a fictional story of two lovers which he weaves into two songs, with “Glued Myself Shut” tracking their slow drifting apart, and “Maine” as a nostalgic reflection on what has been lost. Listening to these songs, I was fully immersed in this tiny New England town of slow-moving but genuine people, of early mornings out on the harbor, of boats floating in the sunset, and of the steady rhythm of waves against rocky shores. Like all good storytellers, Kahan captures an incredible feeling of authenticity in his fantasy through carefully constructed details that are both mundane and almost mythical at once, with lines like “We gambled our souls to the summer” and “we rattled our bones to the thunder.”

One line from the piece “Maine”, in which Kahan’s character reminisces about his old lover, repeated in my head over and over: “Laughing at the way, that you would say ‘If only baby there were cameras in the traffic lights, they’d make me a star.” It’s the kind of special, intimate, and almost absurd secret we tell the people we love and trust most — playful, sentimental, and deeply personal. It made me feel almost voyeuristic, like I was intruding on a private moment, but Kahan does not try to hide or reject us — he invites us in and embraces us, engulfing us in his story.

In a summer of personal loneliness, wanderlust, and the persistent desire to experience genuine human connection, Kahan’s album was a gift: both a comforting reminder of emotional intimacy, and a scenic escape from quarantine.

— Sandy Yang ’22

In just about every era of human history and society around the globe, music has served as a way for people to express their emotions and connect with others. Especially now, during a global pandemic, music is more important than ever in helping combat the isolation and stress that seems to inevitably find its way into our daily lives.

For the past few months, I’ve been listening to the Audiotree Live album of one of my favorite artists, Current Joys, as my own way of destressing through music. The Audiotree Live recording features songs from their newest release, A Different Age, which documents the process of making art and the desire to create it sincerely in an era fraught with apathy and nostalgia.

Nick Rattigan, the creator of the band, started the project as a way to unify his love for film and music and has directed multiple music videos for the albums they have released so far. Rattigan, who suffers from generalized anxiety, has stated that the project has helped him free himself from the stresses of his condition and that he hopes to offer the same catharsis for those who share his experience. The songs contain some of Rattigan’s most poetic lyrics and thoughtful arrangements to date, but with a fresh and thunderous sound as they are performed live.

As someone who loves attending concerts as a way to escape the chaos of daily life, I appreciate how the Audiotree recording of A Different Age offers the same passion and spontaneity of Current Joys’s live performance from home.

— Silvana Parra Rodriguez ’24

Leila Chatti’s poem “Tea” is one that I find myself re-reading and turning to often these days. Those who know me may be surprised by this fact — after all, I myself do not drink tea. But reading this poem fills me with the sort of warmth that tea might evoke for others. The poem reminds me of how important self-love is, especially in this time when it is so easy to forget to pay attention to ourselves. As Chatti reminds us, the ability to create warmth and happiness for oneself is truly a superpower. Through the use of tea, a simple motif, Chatti tackles important issues of identity, culture, and colonialism. This poem motivates me to do the things that are most necessary: to listen, to reflect, and to write.

— Uma Menon ’24