What We’re Loving: Winter Break 2020 Edition

Source: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston

As a young student taking her first steps into the real world, I feel a little silly sharing my thoughts about Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle — a snappy, satirical masterpiece illustrating the reflections of a World War II veteran, former prisoner of war, and trauma-laden humanist. Thankfully, a) this is a “what we’re loving”, and I’ve fallen in love with this book, and b) I think I’ve reacted the way Vonnegut would’ve liked a reader to — that is, almost two months after reading, my mind still flits back to moments in the story, pondering upon the repulsive mundanity of its characters and events, and unwittingly drawing parallels to moments in our beloved world of today.

— Abigail McRea ‘23

When Breath Becomes Air (By: Dr. Paul Kalanithi)

I initially picked When Breath Becomes Air up because it was a memoir written by a medical doctor who studied literature as an undergraduate student—what an interesting combination! Though an expert in the natural sciences, Dr. Kalanithi brought with him a natural ability to weave philosophical thoughts into his elegant and intentional prose. A young Indian-American writer, husband, and father finishing up his last year of neurosurgery residency, Dr. Kalanithi mirrored many of the values—resilience, faith, and courage—that I have been raised with and continue to project into my life. He pursued both English Literature and Medicine, completing graduate degrees in each respective field. Though he initially studied literature to investigate the larger questions surrounding human mortality and biological life—what it means to keep living in the face of death—he quickly realized that the best way to formulate answers for such questions was by practicing medicine.

Although many expect this memoir to dissect Dr. Kalanithi’s decades-long journey of balancing a multitude of passions, he instead beautifully—and painfully—chronicles his last year of life after being diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. With this rather unexpected diagnosis, Dr. Kalanithi was suddenly forced to confront the very questions he had once investigated in literature. As cancer further invaded his life as a neurosurgeon, he chose to turn towards words and books for comfort. And, though science and biology once prominently informed his understanding of the world, Dr. Kalanithi realizes that this understanding will evolve as he is intimately confronted with death. He realizes that it is the humanities—writing, reading, and literature—which give him space to unpack his uncertainties and grapple with his identity as a doctor and patient. With this realization, he traces his ongoing battle with cancer and his understanding of human life, pushing readers to ask themselves “what they would do when the future, no longer a ladder toward your goals in life, flattens out into a perpetual present?”

When Breath Becomes Air has challenged me to reflect on what it means to turn to literature to make sense of uncertainty—to seek meaning in words when the world you once knew is rendered meaningless. Readers are led through Dr. Kalanithi’s many battles—whether they be physical or emotional. We see fear weaved into his movements as he performs his last surgery in the operating room, afraid that he will never return. We recognize his bravery in choosing to have a child with his wife as a means to nurture a new life as his own begins to weaken. We’re put face-to-face with the rawness, pain, and beauty of it all—of how Dr. Kalanithi investigates mortality, first as a young student eager to understand the possibilities of human life and then as a patient battling a terminal illness.

— Aditi Desai ‘24

Source: IMDB

As someone who feels at best neutral towards most forms of organized sports, I found myself surprisingly invested in Ted Lasso, a comedy about an American football coach hired to turn around a failing British football (soccer) team. What sounds like the setup to a joke (and, in fact, originated as a sketch from an NBC commercial) is turned into an exploration of forgiveness and friendship that is given genuine emotional heft by its well-rounded characters. Ted, the titular coach, is unfailingly optimistic in his attempts to build up the team’s trust in themselves and each other. His optimism is saved from becoming outright naivete, however, through the insights we’re given into his own struggles with his slowly declining marriage. He’s not a cartoon character, cheerful to the point of delusion, but someone who chooses deliberately and repeatedly to view the world with curiosity and compassion instead of judgement.

The show’s emphasis on honesty means that interpersonal problems are dealt with head-on, precluding the kind of drawn-out drama hinging on a lack of basic communication that often frustrates me in sitcoms. The female characters, too, are given fully formed ambitions and friendships, and the dialogue takes an unexpected delight in wordplay: “What if I joined forces with a swashbuckling cat to play tiny guitars for women of the night as we read Alex Haley's most seminal work?” “You'd be in cahoots with Puss in Boots playing lutes for prostitutes reading ‘Roots’.”

By the season’s final match, even I, who has been known to root for the opposing team if it means a game might end more quickly, felt as caught up as the screaming fans in the (fictional) stands. Spoiler alert: the team doesn't win, in the end. They face a demotion from their premier league as a result. Not even Ted can simply take this loss in stride. Yes, it is sad, he tells his dejected players afterwards in the locker room. But at least, and most importantly, none of them are sad alone.

Cheesy? Maybe. But honestly, as I sit typing this up from my single in quarantine, being able to sit with a bad situation and know that I’m surrounded by friends is something I’d give a lot to do right now.

— Batya Stein ’22

Source: PBS

My latest obsession could be summarized in a single sentence: Tom Hiddleston as Henry V. But more than that, The Hollow Crown is Shakespeare stripped down and laid bare: adapting five of the Bard’s great history plays, the PBS series grounds lofty language in a gritty, somber Medieval setting, highlighting tour de force performances from Sophie Okenedo, Jeremy Irons, Benedict Cumberbatch, and many more. It is a loving exploration of family, love, and vulnerability; it is an incisive excavation of power and the corrupting forces that can destroy a nation from the inside out. In other words, it is truly Shakespeare for 2021. Oh, and in case you weren’t quite persuaded yet, Hiddleston delivers the St. Crispin’s Day speech—yes, it’s as amazing as it sounds.

— Cassy James ‘23

Source: https://twitter.com/rt0no/status/1327889479940538369 , art by @rt0no

Despite the language barrier, I quickly became mesmerized by the artwork of @rt0no on Twitter, whose captions are typically in Japanese. Their haunting digital illustrations feature anthropomorphic characters who are reminiscent of nursery rhymes and children’s books, like The Three Little Kittens or Alice in Wonderland’s White Rabbit. Their subjects of choice are often foxes, crows, and crocodiles, who are presented in protective roles despite their predatory teeth or beaks, as well as cats and rabbits, often vulnerable, child-like, or in families like above. @rt0no’s style is what I found particularly alluring: it combines innocence and sweetness with horror, making use of drab colors and the eerie animal head/human body combination, on top of morbid settings (cemeteries, stairwells, or on checkboards). Their work is also irresistibly steampunk, meaning it fuses the historical with futuristic or technological elements. The latter themes often come from @rt0no’s choice of digital medium, as well as the inclusion of freakish characters, modern cafes or bakeries, and the occasional anime girl. Meanwhile, clothing details evoke the past, like the bonnets or collars on the gothic Victorian dresses above. Whether you’re looking for some writing inspiration or comforting nostalgia with a twist, definitely skim through @rt0no’s portfolio here: https://twitter.com/rt0no?lang=en

— Fizzah Arshad ‘24

Source: Marvel Studios

I’ll preface this WWL by acknowledging my bias. Scarlet Witch (alias Wanda Maximoff) and the Vision are my two favorite Marvel superheroes. The unusual yet sweet romance between Elizabeth Olsen’s Wanda Maximoff and Paul Bettany’s Frankensteinian synthezoid Vision has captivated me since the release of Avengers: Age of Ultron. I can’t tell you how ecstatic I was to hear that my favorite ship would get their very own show.

I’m happy to report that WandaVision has exceeded my expectations, and will certainly appeal to those unfamiliar with or disengaged from the Marvel Cinematic Universe (CU). For those who tend to shy from anything with a Marvel label, I beg you to give this show a try. I promise you don’t have to watch all 23 Marvel movies to truly enjoy it.

WandaVision comes in stark contrast to its predecessors. There are none of the MCU’s characteristic flashy CGI battles, flat villains, or endless quips. Instead, WandaVision takes its inspiration from several classic shows, ranging from Bewitched to The Brady Bunch. The plot centers around the Wanda and Vision’s antics as a newly-wed couple trying to make a home in the small town of Westview. Immediately, things are not as they seem. Whether it's the prejudices of the time period or a mysterious beekeeper emerging from the sewer, there is always something sinister lurking beneath the show’s shiny suburban exterior. The mysteries of Westview are immense, but these unknowns leave the viewer eager to see more.

Elizabeth Olsen’s performance is especially great. She plays both a charming housewife and an unstable witch with ease. Watching her switch between the two personalities is both fun and frightening (you’ll see). I can’t wait to see how she continues to develop the complexities and chaos enshrined in Wanda Maximoff.

The fourth episode (out of nine) was released on January 29. Episodes release every Friday on Disney+.

— Katie Rohrbaugh ‘24

Source: RCA Records

On November 27, 2020, American singer Miley Cyrus released her seventh studio album entitled Plastic Hearts, marking both the tail end of a universally tumultuous year as well as a significant departure from the sound of her previous discography. Merging 80’s-era influences such as disco and glam rock with modern-day pop sensibility, Plastic Hearts features Cyrus’s strong, versatile vocals on tracks ranging from uptempo punk rock belters to soulful power pop ballads. The album’s crowning jewel, however, has to be the digital edition exclusive track “Edge of Midnight (Midnight Sky Remix),” a mashup of the album’s lead single “Midnight Sky” and legendary Fleetwood Mac frontwoman Stevie Nicks’s 1982 release “Edge of Seventeen.”

As the result of several traumatic experiences, including the loss of her house to the California wildfires and a public divorce from longtime partner Liam Hemsworth, Cyrus had written the original “Midnight Sky” as a means of reclaiming her independence, encapsulating her personal growth, and celebrating her own self-expression. Many of the lyrics make reference to her lost love (“I don’t need to be loved by you”) while also alluding to her post-split romances, which were the subject of heavy scrutiny by the media (“See my lips on her mouth, everybody’s talkin’ now”). In a similar manner, Nicks’s “Edge of Seventeen” was also written in the wake of tragedy, following the death of her uncle and the murder of John Lennon in the same week of December 1980. Its lyrics feature the recurring motif of a white-winged dove, meant to symbolize the spirit leaving the body on death, whose coos are captured in the descanted refrain: “ooh, baby, ooh.” Given the comparable contexts of the two songs—both composed in the face of devastation—it is only fitting that their mashup works so well as a triumphant anthem of resilience.

Though standalone hits in their own right, the marriage of the raw vulnerability of “Midnight Sky” with the mystical sensuality of “Edge of Seventeen” creates a coupling that elevates the best qualities of the originals. Kicking off with the latter’s distinctive, chugging 16th-note guitar riff, the remix launches into its opening verse, in which Cyrus confesses that “it’s been a long time since I felt this good on my own.” As the subdued guitar accompaniment blooms into the resonant chorus, Cyrus’s raspy belt defiantly declares that “I was born to run, I don’t belong to anyone” before pairing with Nicks’s crooning vocals on the iconic lines that follow: “Just like the white winged dove / Sings a song, sounds like she’s singing…” Buoyed by the harmonization of its two powerhouse vocalists, the song continues building up in passionate intensity up until the final climactic end, as it rides out the high of a euphoric freedom, as clear as the air of the midnight sky.

— Megan Pan ‘22

When the fall semester ended, I immediately reached for projects, for things to do, finish, create, contribute to. It was an unnecessary continuation of the momentum that began in August at the very least, at the beginning of the semester. In recognizing both this urge and its un-necessity, I turned to podcasts. Finishing a season or even a whole podcast was an accomplishment in itself that didn't involve overworking myself. (I did, however, find myself staying up to finish an episode or two sometimes.)

In this pursuit, I found Not Overthinking, a podcast hosted by Ali and Taimur Abdaal, the former of which is a productivity YouTuber and doctor whose videos I follow. The two brothers talk about things they think more people should talk about; they name social interaction, lifestyle design, and mental models as some examples.

So, a few weeks ago, I set about listening to the eighty-eight episodes that were out at the time. I found myself constantly bringing up what they talked about in conversations with friends, whether it was Taimur's concept of measure, Taimur's concept of low social optionality, or Taimur's concept of kids not being taken seriously enough. I joke; of course, Ali has a lot to offer as well, but I've heard much of it on his YouTube channel. I enjoy coming into each episode having some prior understanding of Ali and being taken on the ride of Taimur's social theories along with him. Taimur's work as a data scientist and startup founder brings a pretty different perspective to the Abdaal Cinematic Universe I was already used to.

I appreciate the additional dimensions Podcast Ali offers, too; he's real about what it's like to be on YouTube, and about the artifice that inevitably goes on when filming for a YouTube channel. Imagine recording yourself for a presentation in class, and then you talking with your best friend or sibling. You're less polished, but more honest. Whatever's really on your mind comes out. That's the kind of contrast that isn't just displayed, but talked about. I eat up that social analysis and introspection.

Plus, like another fan whose podcast store review was read on the show, I found Not Overthinking to be unexpectedly funny. It isn't about the Abdaals; I just didn't expect a podcast billed as being about "happiness, creativity, and the human condition" to make me laugh so much. But it does, especially when there are guests on the show. Often, they are friends of Taimur and Ali, which was a bit confusing at first. These were certainly not experts on transactional analysis or the like. What I ultimately understood is that that's exactly the point. The kind of conversations Taimur and Ali have are about things they think everyone should think more about; their friends are part of that everyone, and so are we as the audience.

I saved their episode on race and episode reacting to responses to their episode on race, avoiding a heavy topic from a podcast I used to relax and, honestly, fearing I wouldn't like what I heard. But, these episodes actually become quite pleasant listening and learning based on their open-mindedness, genuine desire to understand, and epistemic humility. (I'm not exactly sure what epistemic humility means either, but neither do the Abdaals; Ali asks for a definition of "epistemic" practically every other episode, which Taimur consistently struggles to answer. I feel you, boys.) The same goes for their episode on misogyny and generalization. All they ask is that their outlook of charitably interpreting others is applied to them as well; I think it is well deserved.

If you're looking for a project to hold on to, listening to Not Overthinking will more than suffice. This review can't possibly be doing it justice. With my winter break project of catching up on the entire catalogue complete, I can attest: the podcast is not just easy listening, as Taimur likes to say. It calls you in. Ali and Taimur call you in, asking you to engage with their ideas, which they discuss and form right in front of you. Not Overthinking is not just a practice of ideation or a discussion of huge topics like happiness, creativity, and the human condition. It's a conversation between friends, and you are welcome to join.

— Mollika Jai Singh ‘24

Charles Yu, Interior Chinatown

One of the strange silver linings this pandemic has offered is the ability to attend meetings that would ordinarily be closed off to the public, such as the award ceremony for the 2020 National Book Awards. As a writer of Chinese-American descent as well as a fervent devourer of contemporary Asian-American literature, I felt especially proud and heartwarmed when Asian-American writers and translators swept 3 of the 5 National Book Award categories, one of which was Charles Yu’s electrifying novel, Interior Chinatown.

I first stumbled across Charles Yu’s unforgettable style when reading his short story “Fable” in The New Yorker as an assignment for a summer writing workshop. Yu has this uncanny ability to experiment with the prose form in a way that complements the theme rather than work around themes tangentially and brings the reader closer to the interiority of the story rather than distance them. Perhaps this impressive feat is developed from Yu’s decades-long experience as a science fiction writer.

Interior Chinatown is a work which I’ve struggled long to find, a work that acknowledges the place of the Asian-American as a misfit that is neither black nor white, acknowledges that indeed the existence of the Asian-American as a category is itself a means of stripping us of our individuality. It recognizes that the Asian-American model minority myth is just that— a myth. It forces us to reckon with the stereotypes manufactured our minds unconsciously manufacture. It is a reminder that hope for a more equal, more inclusive future survives even in the tumult that was 2020.

— Rui-Yang Peng ‘24

Source: Leon Bridges

“River” by Leon Bridges—from his 2015 album Coming Home—has been a source of personal comfort and healing. The song is simple, stripped down to a guitar and vocals, and the lyrics are a sort of prayer: “Take me to your river / I wanna go.” Leon Bridges, whose soulful music is often compared to that of Otis Redding and Sam Cooke, says, “[‘River’] is basically the turning point, really just surrendering to God. The river represents being baptized, and really just turning everything to God.”

I was raised Christian, but my faith has been rocky, especially over the past year. Somehow, that brings me closer to this song. It’s not that I experience God; rather, I experience the river. The river, as a metaphorical device, appears flexible—its nature is flow, adaptation, relentless being. As I begin to question my belief system, the river appears even more expansive.

The simple texture of the song and the earnest, almost childlike, hunger for the river remind me of humility, of surrender. I think of rivers of affection and goodness in others; sometimes, even, the river is a specific person. I’m thinking about how I can be generous, more devout, in my love of the self. To Leon Bridges, “River” may be about God, but art refuses to be a single narrative. Art lives on largely because of our freedom to interpret, to interrogate ourselves, to simply feel in our own ways. What is the river? What do we bathe ourselves in, what do we commit to? And what does the river awaken in us?

The other day, I was listening to the song and I wrote a few lines of a poem. “River” was grounding; it was soothing and sincere. It’s Leon Bridges tonight. The song is River. Right now I am remembering / to pour the water into the kettle. To love / my father. / The song is River. I need this song.

— Sabrina Kim ‘24

Source: Amazon.in

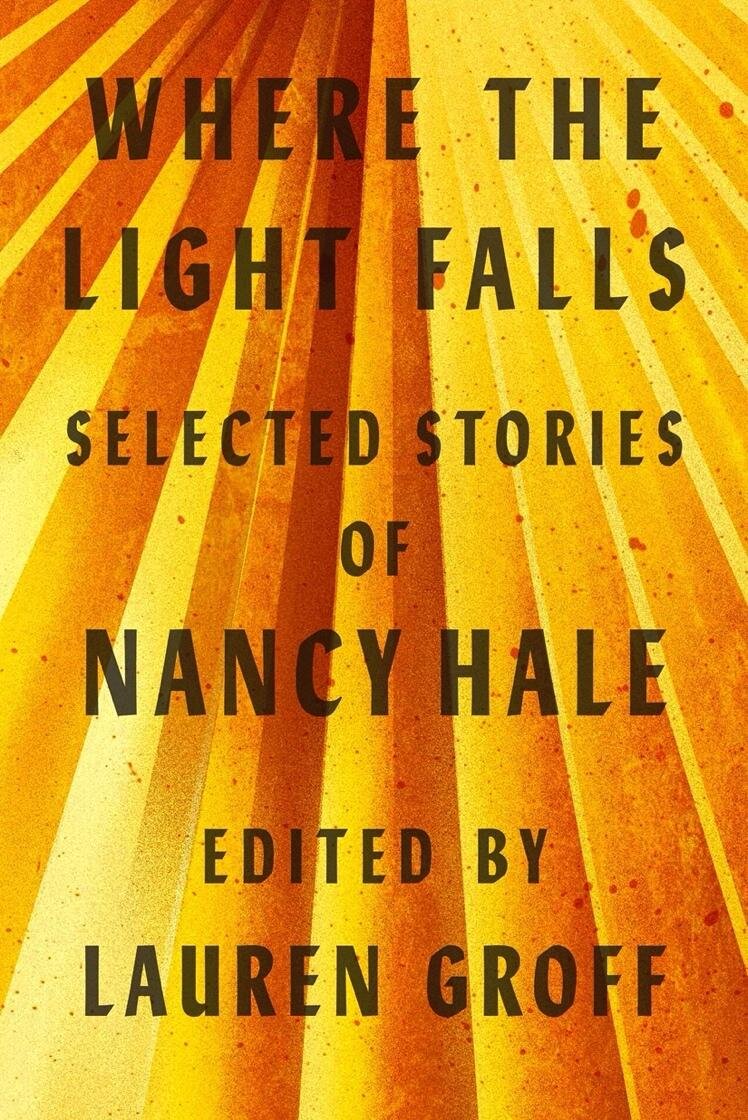

Where the Light Falls by Nancy Hale, edited by Lauren Groff

Twenty-first century readers looking at the sun-drenched cover of the short story collection Where the Light Falls are more likely to recognize the editor’s name, Lauren Groff, than the author’s. Though largely forgotten by the reading world, Nancy Hale was one of the most accomplished practitioners of the short story form. The Boston writer penned over a hundred short stories and won ten O. Henry Awards in her lifetime. This collection is Groff’s attempt to give a deft examiner of secret hurts and political travesties alike her due.

One of Hale’s greatest achievements is capturing the poignancy of everyday life, the small heartbreaks. In ‘Double House,’ my favorite story in the collection, a lonely boy accepts a rare flower from his cheerful father, who’s the child’s only consolation in life. The father tells Robert to make his classmates jealous by showing them the flower. Hale writes, “Robert took it in his hand, looking at his father and unable to say anything. He was so touched by his father’s helping him, and yet he knew so well that he would not knock their eyes out, that if anything they would only find his new flower an excuse for laughing at him.”

These stories make us care about even the trivial things their characters yearn for. In ‘Crimson Autumn’ we understand why a 1930s debutante feels powerless to leave her wealthy Harvard boyfriend even though he exhausts her. We feel how important it is for Melissa to be “Davis Leith’s girl” in ways that feel both dated and contemporary. Hale’s imagery is full, sensuous. We see characters “lying still between two smooth slices of sheet.”

Until I read Lauren Groff’s LitHub essay on the forgotten genius of Nancy Hale, I was also a reader whose eyes would have slid over this golden book. Yet this collection contains some of the most luminescent, virtuosic stories I’ve ever read. Hale’s writing is as illuminating and feels as natural as morning sunlight.

—Ashira Shirali ’23

Art by Owen D Pomery (Untitled - Tribute to local bookshop)

Owen D Pomery is an artist based in London. A member of the Society of Architectural Illustrators, he tends to focus on places and spaces, with meticulous, precise details in the buildings and landscapes that surround his miniature human figures. Each location feels richly rendered, from the bricks and cobblestones in city streets to the ice floes in the Arctic, and his lines and shading are very clean. The colors and lighting tend to evoke a tranquil, restful mood, with depictions of ordinary life or a languid vacation by the shore.

Pomery posts his work on his Twitter (ODPomery) and his personal website (owenpomery.com).

— Sydney Peng ‘22