What We’re Loving: New Staff Edition 2021

Source: gadgets.ndtv.com

A cast brimming with mainstream names, a blockbuster budget to rival Avengers: Infinity War, and a runtime that guarantees at least two bathroom trips—Dune (2021) is at times a lot of work and overwhelming, but it ultimately delivers on its promise. The second film of this planned trilogy has already been greenlit, and we’re eagerly anticipating it.

Dennis Villeneuve is no stranger to big ticket sci-fi, having directed cyberpunk classic Blade Runner 2049 and mind-bending extraterrestrial Arrival, not to mention high-stakes thrillers like Prisoners, Sicario, and Enemy. Dune is a special case because of its long and winding history of attempted adaptations—no surprise that it proved hard to translate a novel with such epic scope to the screen. But Villeneuve’s Dune is hardly an exercise in slow worldbuilding; instead, it grabs the viewer and shows us each carefully explored facet of Frank Herbert’s universe, from the magnificent mouths of sandworms, to marching Sardaukar, to the tormented Lady Jessica’s frenzied ruminations. The juxtaposition of cold, posthuman interstellar travel scenes against hot-blooded, sweltering desert combat shows us a world simultaneously distant from and close to our own. A bit of background before viewing may help, but either way, this film will have you sandwalking and dreaming of melange when you leave the theater. A must-watch.

— Yejin Suh ‘25

Source: canadianfilmday.ca

Horror movies have a well-deserved bad reputation for treating women and minorities as expendable or as spectacles of torture, but recently there have been beautiful strides to flip the script. From cerebral and psychological horror films like Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) and Us (2019) to a brand new take on vampires in Ana Lily Amipour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014), more and more movies are challenging the notion of what horror is ‘supposed’ to be. My current horror-subverted obsession is from the very early aughts: Ginger Snaps (2000), directed by John Fawcett.

It’s a story about coming of age, about sisters, about embracing the macabre and grappling with trauma all while refusing to die. It’s a story about growing hair all over, feeling sudden rage and despair, having weird cravings, and dealing with a lot of blood. Is it about puberty? Is it about werewolves? Yes.

If you want to have a scary good time (complete with a Jennifer’s-Body-esque slow walk down a school hallway scene), I’d highly recommend watching Ginger Snaps (2000). As with all works of horror, I’d also recommend checking out the Does The Dog Die page ahead of time to check for any content you’re not willing to watch. You can find that page here: https://www.doesthedogdie.com/media/9749

— Rosemary Dietz ‘25

Source: denofgeek.com

Fleabag, a multiple-award-winning Amazon Prime Original, written by, directed by, and starring the unparalleled Phoebe Waller-Bridge, says exactly what we’re thinking with lines like, “You know, either everyone feels like this a little bit, and they're just not talking about it, or I'm completely f***ing alone,” and “I sometimes worry I’d be less of a feminist if I had a bigger chest.” This dark comedy slyly snuck its way into my collection of comfort shows, skillfully pairing the strange and familiar through portrayals of emotionally unavailable fathers, sex addictions, and grief over the death of one’s ephemeral youth. You can guess which is which.

The protagonist is unnamed and is instead referred to as Fleabag or nothing at all. We follow her through vignettes of the perpetual crisis of her tumultuous thirties and eventually become well acquainted with her as a true anti-hero. However, the show is crafted to convince you of the familiarity of Fleabag, as if you are traipsing around inside her morally ambiguous mind; more than once I had to pause and remind myself her actions were not, in fact, justified.

Fleabag has me asking all sorts of questions like...how do I recommend to my Catholic mother a show in which the protagonist lusts after a priest? And how did a conversation about a bad haircut between the protagonist and her older sister make me sob for an hour and a half?

The show is deeply intimate, and not simply because Waller-Bridge breaks the fourth wall every third sentence, but because of its depictions of grief, guilt, love, lust, depression, and very poignantly for me, sisterhood.

This masterpiece truly embodies range. In fact, what viewers believe to be the focal point of the show is startlingly diverse: everything from feminism to self-loathing.

The show is shocking, blasphemous, and downright hard to watch at times, for more reasons than one, but it reflects expertly on both the sorrows and the joys of the human condition behind a veil of quippy humor.

— Noelle Carpenter ‘25

Source: The New York Times

I’m passionate about history, but part of what I seek most from it is also what makes it so frustrating. I’m interested in the major facts and events, of course, but I’ve always wanted to know more about people’s lives behind the scenes. What did people think and feel? How did they see themselves; how did they want to be remembered? How much were they like us and how did they differ? How do we—or how can we—connect history’s major events to the human beings behind them?

I’ve found an answer to part of this immeasurable question in Hilary Mantel’s book series Wolf Hall, begun in 2009 and completed in 2020, now with award-winning adaptations for television and stage. I’m currently reading the final book of the trilogy, The Mirror and the Light. I admit that when I first started the series, I struggled to adjust to Mantel’s prose, which was beautiful but so detailed as to be overwhelming amid its accurately-drawn cast of characters and scenes.

Then, something clicked halfway through the first book. I think it was Mantel’s depiction of grief—her poignant, devastating reflections on such a universal experience—that hooked me completely. She humanized the series’ main focus and perspective character, Thomas Cromwell. Mantel made me care about him, made me anxiously await what would happen next, even though I was already aware of the major historical narrative forming the backdrop of the series.

Even though I know what happens to Cromwell in the end, I catch myself consciously slowing down as I read the trilogy’s final novel. I don’t want to reach the book’s inevitable conclusion because it means leaving this world, leaving these characters, who are real and not real, representations and fabrications, at once markers of our historical separation and mirror-like glimpses into ourselves. As Mantel writes in Wolf Hall, “Some of these things are true and some of them lies. But they are all good stories.”

— Claire Schultz ‘24

Source: a24films.com

The Haunting of Bly Manor was my introduction into the horror TV series genre. It follows Dani Clayton, a young American in the United Kingdom who has been newly hired to be an au pair for two children, Miles and Flora, at the Bly estate. The estate itself is too large, and Dani finds herself caught within the empty spaces. She is tangled in the lives of the two children, the other workers, and those who had lived on the manor before. Dani finds herself reconciling the manor’s history with its present horrors, forcing her to confront her own past.

I had been accustomed to horror movies, to anxiousness and fear stitched together into no more than 120 minutes. But The Haunting of Bly Manor is not a mad dash to survival, a sprint to safety and solace. The Haunting of Bly Manor crawls. It slowly extends its limbs episode after episode, dragging itself against grief and terror. The show is scary, but it is the type of horror that digs underneath your skin, that wraps around your bones and groans under the weight of your anxiety.

But The Haunting of Bly Manor is more than a horror story. It is also a love story. It doesn’t crawl towards safety but towards a person, towards someone to hold onto. Someone who can fill the cracks and make the past no more than a memory. The show is so horrifying because there is so much at stake. The Haunting of Bly Manor is both sweet and destructive. It gives me warmth and happiness and the sweet scent of flowers, but never once lets me forget that such things can be lost.

— Ash Hyun ‘23

Source: levaire.com

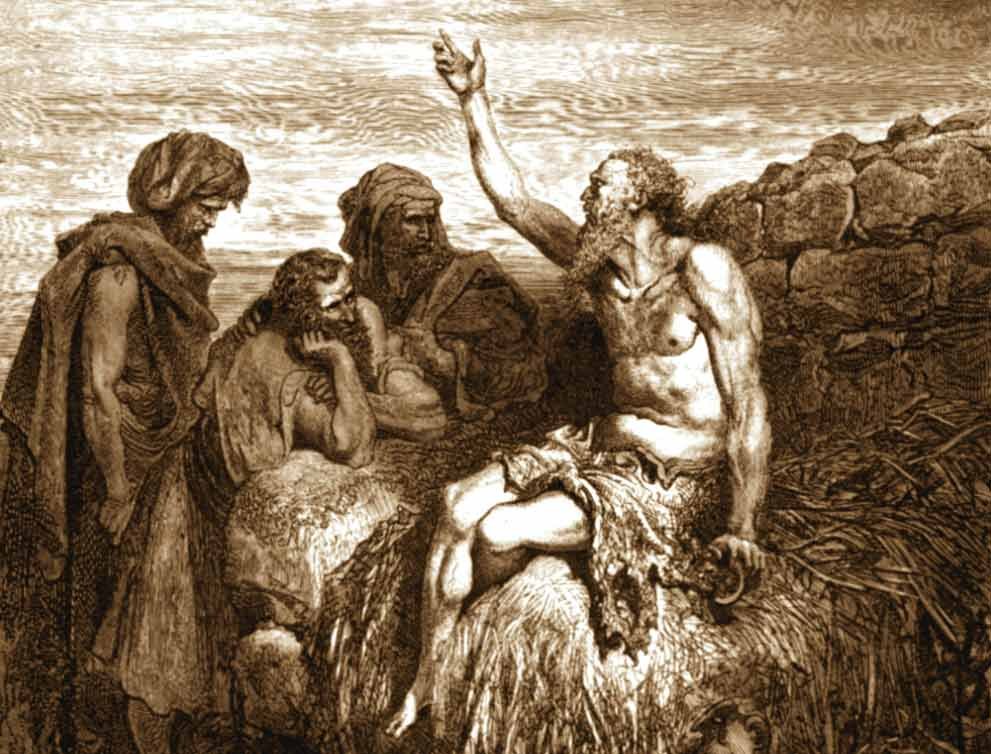

Let me first disclaim this blurb by mentioning I have no religious upbringing whatsoever—my only exposure to the contents of the Bible were VeggieTales and the stained glass of cathedrals that I perused as a tourist. But that changed when I read the Book of Job as homework for ENG 390, then picked it apart with professors the next day in class, and then read it again on my own time in spite of the one hundred other assignments that forever and always loom.

The story or parable or biography (your choice) tells of a man unjustly stripped of everything he has at the hands of his God as a test of his faith. The Book includes conference calls in heaven between God and a devilish figure as they plot the destruction of Job’s fortune, gutting monologues from a man wallowing in a pit of despair, and a horrifying description of the monstrous Leviathan. Traditionally, the merits of this book are attributed to its exploration of the difficult issue of theodicy––why might a just and all-powerful God allow humans to suffer?

Yet what distinguishes the Book of Job for me is its incredibly sincere and nuanced depiction of human suffering. This book seems comfortable not fully answering the questions it asks and instead sees the value in simply sitting with the pain of another as if to relieve some of its sting, just as Job’s friends join him in silence for seven days as he mourns. Similarly interesting is the book’s role within the larger context of the Scripture. Unlike any other story of the Bible that I’ve now read with the exception of Song of Songs, Job’s story can completely stand alone, just as easily working as a powerful short story than as a sequential element in the Bible’s narrative.

It started as homework and finished as a story I can confidently say I love. Whether you’ve never touched the Bible or look through its verses everyday, the Book of Job will never fail to move you.

— Tristan Szapary ‘24