What We Loved in 2014

Early this year I started a playlist of mellow music, and I have been adding to it mindlessly over the past few months as I discover new songs or rediscover old ones. It is now over six hours long, and I don’t think I have ever listened to it in its entirety. This October, while packing for fall break, I left that playlist on in the background, and a song came on that I didn’t recognize. As it played, I felt suddenly taken by it. The music and lyrics were so simple, but the song carried an intimacy I so rarely heard in other music. Looking on the screen, I learned that the track was called “Of Desire” and was by the Australian music duo Big Scary. I discovered Big Scary through a Spotify ad that played in 2013 when their album Not Art came out. The best description I have for Big Scary’s music is that it is simultaneously otherworldly and evocative. There is something about their songs that always seems to take me to another place. “Of Desire” is from Big Scary’s 2011 album Vacation. I must have heard it at some point in the spring, liked it, put it on my playlist, and then forgotten about it. However, after hearing the song again in the fall, I couldn’t stop listening to it. I played it over and over that day and all through fall break, the song successfully conveying my state of feeling in a way that I couldn’t myself. Months from now, when I listen to the song, I know I will be brought back to 2014. I will remember how I felt sitting on the couch at home with that song on repeat and the people and things that mattered so much to me this year.

— Andrea D’Souza

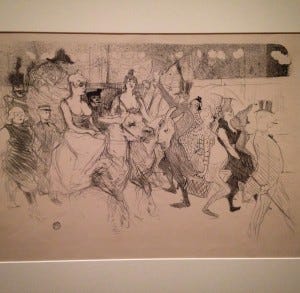

With around one hundred prints by the silent observer of Paris’ night life, MoMA’s “The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec” was my favorite art exhibition of the year. Toulouse-Lautrec’s gestural line contrast with blocks of stark color to bring a sense of urgency to his scenes, which range from film posters to portraits of Parisians, including a series of lithographs titled Elles that depict prostitutes during non-working hours. I visited on a UNIQLO free Friday night, where the energy in Toulouse-Lautrec’s scenes transferred to the summer crowd of New Yorkers, young and old. You still have time to catch the exhibition, which runs till March 22nd, 2015.

— Vidushi Sharma

The first novel of British writer Jonathan Gibbs, Randall tells the story of…well, Randall, the greatest ‘90’s artist who never lived. The career of Randall, recounted by investment banker and Randall insider Vincent, is framed by the story of Vincent’s post-Randall struggle to deal with his friend’s (self-doubt inducing) (impossibly secret) (romantically charged, obviously) (downright) explosive legacy. The novel explores the ways in which audiences of art are incorporated into the art itself, the tense transition between the shock of a new idea and its historical permanence, and the tightrope that conceptual art walks between absolute brilliance and total farce. Read it for the clever turns of phrase and for the domineering character Randall, a figure almost as fantastic and unbelievable as he is suggestive of those quirky self-preening maybe-geniuses that you might have met and ground your teeth at — and listened to.

— Ayelet Wenger

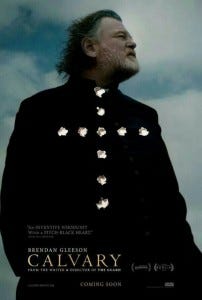

A priest walks into a bar and watches as his church — a few hundred meters away — burns completely. In some ways, writer and director John Michael McDonagh does indulge in the joke in Calvary. This Irish gem of a film, which premiered at Sundance, stars Brendan Gleeson as a well-meaning priest, Father James, who must get his house in order after receiving a death threat during confession. It’s clear almost immediately that Father James recognizes the man on the other side of the booth as one of his parishioners. McDonagh doesn’t seem too concerned about who the viewer believes this parishioner is. In fact, it’s probably pretty clear. If you can get over this hump, you find that the film is thinking about many other things. Though this is no comedy, much of the film’s humor comes from Father James’ interactions with the profligate members of his congregation. (And there’s a guido-like male prostitute somewhere in there, too.) What makes Father James interesting to watch is that his faith endures long after he’s recognized that the world of women and men is often shitty and inconvenient. The humor is self-effacing, and thus the film avoids pedantry. The moments of solemnity are equally appropriate, as when Father James comforts a French window in his church or when he reconciles with his estranged daughter (Kelly Reilly), who was born before he became a priest. The combination of Patrick Cassidy’s wall-of-sound score and Larry Smith’s gorgeous camerawork elevates the film to something verging on the sublime: strands of lightness floating atop a dark body of water.

— Aaron Robertson

My favorite discovery of 2014 has to be Sam Smith. Although his star-making hit was this summer’s “Stay With Me”, I find his acoustic numbers much more compelling. Check out the live version of “Lay Me Down” and his cover of Whitney Houston’s “How Will I Know” in particular — the pared-down instrumentation showcases Smith’s vocals at their soulful, lilting best.

— Whitney Sha

Halfway into his set on his debut standup album, Waiting for 2042, Hari Kondabolu addresses the criticism that he’s obsessed about talking about race. The New York comic offers a few who would disagree: Trayvon Martin’s parents, Oscar Grant’s family, anyone in Guantanamo. “Accusing me of being obsessed with talking about racism in America is like accusing me about being obsessed with swimming when I’m drowning.” The audience cheers, and then Kondabolu laughs at himself: “And that was the slam poetry section of the show.” Kondabolu is a political comedian; growing up in Queens and living in today’s world, he feels it’s hard not to be. His set list reads like the talking points of a progressive platform: healthcare, women’s rights, and immigration reform. Ripping into these issues, Kondabolu is aware that the comedian has real power to influence the way people see and feel. He’s also aware that a comedian needs to tell jokes. Kondabolu feels the push and pull of these dual responsibilities on stage: he’s somewhere between an activist at a rally and funnyman raconteur. The tension has created the comedy album I needed most this year. Kondabolu says he looks for jokes in what makes him angry, and there’s a lot to be angry about. His quote about drowning could be found pasted on posters among the signs protestors carried in New York City after the Eric Garner decision. There, the words didn’t sound anything like a joke.

— Will Lathrop

I am a sucker for soul, or the invented idea of it, and there were few places this year I found it more deeply than etched in the expressive lines of Brendan Gleeson’s face in Calvary, English director John Michael McDonagh’s moody exploration of a movie. Gleeson, in a towering performance, plays Father James, a flawlessly good Catholic priest stationed in a tiny Irish parish full of characters who are nothing if not flawed. These characters, although often ridiculous, are beautifully acted and hauntingly familiar, for all their outlandishness. They revolve around Gleeson’s immovable priest like floating, amoral planets orbiting a fierce but dying sun. The film is full of pounding, powerful music and sweeping shots of the stark and stunning Irish landscape. This is reason enough to see it. But what is most striking is the foreboding sense of melancholy that is infused throughout: In the expanse of Gleason’s masterfully controlled countenance, in the tenderness with which he treats his fragile daughter, in the cruelty with which his kindness is returned, what we find is a lurid and twisting, dark but not hopeless portrait of the multifarious human soul.

— Kyle Berlin

Taylor. Allison. Swift. 1989. Enough said.

But in all seriousness, unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve heard, or at least heard of, Taylor Swift’s latest album. Inspired by the pop sounds of the 80s, 1989 is a far cry from Taylor’s 2006 self- titled debut album. The new CD is filled with catchy pop tunes that use synths instead of banjos. However, I would caution listeners that the best songs are actually not the singles that have been released. The more sophisticated (read PG- 13) lyrics show that Taylor isn’t the same seventeen year old we were introduced to eight years ago. My personal favorites include “Clean,” “Style,” “This Love” and “Wildest Dreams.” Even better are Taylor’s secret messages from the lyric booklet.

— Ashlyn Lackey

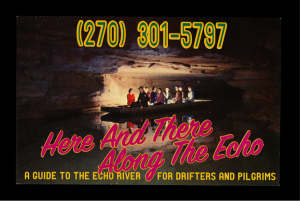

If you call (270) 301–5797, you’ll hear a bit of tinny carny music. Then you’ll connect to a telephone helpline called “Here and There Along the Echo: A Guide to the Echo River for Drifters and Pilgrims” (a public service provided by the Bureau of Secret Tourism). Echo River is in rural Kentucky, and your guide to it is a raspy-voiced male, sounding old and bearded — I pictured a Stinky Pete-type figure preserved in a jar of rotgut. For fear of ruining the fun, I won’t tell you more about the options he presents you with upon calling. But if you enjoy Welcome to Night Vale, you will enjoy this, no question; you’ll also enjoy it if you just have a spare moment that you want to spend befuddled.

But what is this thing, and where does it come from? The area code 270 indeed belongs to western Kentucky, around Bowling Green. Echo River seems to exist — in real life, I mean. And the most cursory internet sleuthing turned up a Guide-affiliated website, which tells visitors to call the number and links to the eBay auction of a “Weird Telephone, only dials one number” (already sold for $315.00, shipped from Elizabethtown, KY). But I don’t think I’ll click on the next Google link. I’d like to preserve the mystique. Echo River’s is a weird world, and what a weird world ours is for having created it.

— Terry O’Shea