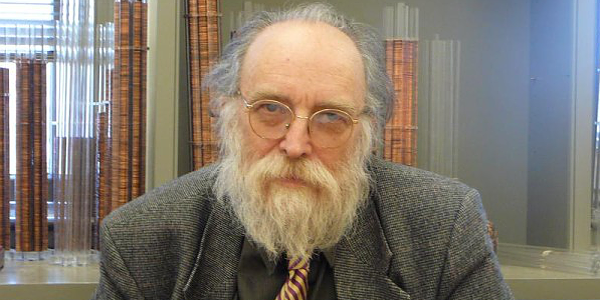

The Impotent Decoration: An Interview with P. Adams Sitney

P. Adams Sitney is on the way out. After thirty-four years at Princeton as one of the University’s most celebrated humanists, passionate teachers, and respected (if also notorious) art critics, Sitney is finishing up next fall with two obscure seminar courses. He intends these seminars, he says, to be as esoteric as possible and to attract as few students as is feasible. One will be on the work of Stan Brakhage, the visionary American avant-garde filmmaker, and the other will be on “something else guaranteed to be of interest to very, very few students”. Professor Sitney is finished, and he’ll make his exit from the academy not with a bang but a whimper — and more than likely, with a huge grin and a fully erect middle-finger pointed at FitzRandolph Gate.

This, at least, would not surprise many of his students, I expect. Its chutzpah, certainly not. Professor Sitney is an infamous eccentric, incredibly opinionated and incorrigibly vocal, especially about his criticisms of the University and university life. According to him, the English department is more or less a disgrace, the Writing Program a scandal[ref]Not to be confused with the Program in Creative Writing, the Princeton Writing Program involves compulsory Writing Seminars for freshmen.[/ref], and Lewis Center for the Arts is the worst thing that could have happened to the Arts at Princeton. Courses are becoming easier, students lazier, and standards, of course, much lower. “It’s entirely possible to get a genuine education at Princeton,” he clarifies, but it’s much easier to “pursue the trendy, the easy, and the conventional”– maybe take “Kiddy Lit” and “American Cinema”.[ref]Courses which Professor Sitney often (vocally and explicitly) criticizes for their “trendiness” and “lack of rigour”.[/ref] But even if you do work hard and take serious courses the University remains, claims Sitney, the “great enemy of poetry.” Artists are stifled and intellectuals are disregarded; only the production of wealthy alumni is really of import here. If we can produce a senator or two, that’s a bonus. The culture of the University is a culture of success and optimization; it is not a culture friendly to poetic thinking. The ideal of this culture is that nothing be uncoordinated or unscheduled, and nothing, if we get our way, should happen by chance or for no reason.

Yet it will be pointed out that if P. Adams Sitney objects to the academy and its culture, he does so as a thoroughly academic creature. As a thinker, reader, and critic of very wide scope, Professor Sitney has long been a stalwart both of the academic humanities and of creative arts at Princeton. He’s offered classes in Comparative Literature, Visual Arts, and Philosophy, and taught many times in the HUM Sequence.[ref]Princeton’s rigorous two-semester survey course for freshmen in the Western literary, artistic, and philosophical canon.[/ref] He has served as the faculty chair of the Behrman Undergraduate Society of Fellows, spoken at the Human Values Forum, and several times served administrative roles in the program for Visual Arts. Sitney has not simply done these things to keep busy; he very obviously loves what he teaches. Though his main scholarly interest is in film history — his appointment is after all as a professor of Visual Arts — he has an unusually deep interest in and acute sensitivity for many modes of expression. Literature, poetry, painting, even philosophy: he effuses about it all, with an urgency and passion verging, at least tonally, on the prophetic. He is fond of a quote from William Carlos Williams:

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.[ref]“Asphodel”, That Greeny Flower, William Carlos Williams, 1962.[/ref]

But the love-hate relationship, if it is not too trite to call it that, between the academy and its creatures — its students and its professors — is one which all of us would recognize in one guise or another. We are always caught between wanting to be here and wanting to be beyond here. The Nassau Literary Review sat down with Professor Sitney to discuss this situation. We wanted to hear his story and understand what critique or advice his experience might incline (though we shy away from saying entitle) him to give.

***

INTERVIEWER

How did you get to be here, to be a Professor? And at Princeton? As I understand it, you took something of a garden path.

SITNEY

Well first I thought I would be a Greek professor; I thought that would be a great thing to do. The University of Chicago used to take people before they graduated from high school, so I applied there when I was in high school but I didn’t get in. I applied again when I was a senior, and I still didn’t get in. I tried for Stanford too, but I didn’t get in there. I didn’t get into a lot of places though — I had a very spotty high-school record. But there was a Greek professor whom I knew at Trinity College — James Notopoulos — and they offered me a full-ride. I could also have gone to Yale, which was in my home town, or to NYU. But at the time I didn’t want to be in New Haven, so I chose for my first year to go to Trinity, where I took Greek and studied with Notopoulos.

But fairly soon after that, he came down with Tuberculosis. And, coincidentally, my parents split up, and both of them were moving out — my mother to Bridgeport, my father to Branford — and suddenly, Yale looked much more amenable.

So, I took a year off, because I was invited to lecture in Europe. During the time I was on that lecture tour Notopoulos’s condition didn’t get any better — he was going to stay in the sanatorium indefinitely — and so I applied to transfer to Yale. Quite fortuitously, just at that moment the Yale Classics department had changed radically. Eric Havelock came form Harvard, and he brought a whole bunch of people with him; it was very exciting. So I stayed at Yale. I was also beginning to lean toward Sanskrit — I thought maybe I’d do that in graduate school. But of course all of this time, the big issue lingering for me was going to jail. I knew I’d go to jail.

INTERVIEWER

What did you do?

SITNEY

I was a conscientious objector. As a Roman Catholic, I wasn’t going to be given Conscious Objector status by the draft board. Yet, from the time that I first had to sign up for the draft at 18, I always sent letters saying that I was a conscientious objector. After my hearing by the draft board, I knew I would be denied — which I was, eventually. So, that threat continued to loom as I graduated from Yale, which was after the fall semester; and I went immediately to the Yale graduate school in Sanskrit.

INTERVIEWER

Immediately after graduating?

SITNEY

Before I even had my diploma. I completed my courses in January, and was accepted by graduate school for the second semester.

INTERVIEWER

Just like that? That doesn’t sound like the usual practice.

SITNEY

Well, they all knew me. I was one of two undergraduate students taking advanced Sanskrit, and I was just going to take a bunch more courses. Further, the graduate programs were being depleted like mad. See, Sanskrit was in the East and South Asian languages department, so everyone was being drafted who spoke any modern South Asian language — it was the height of the Vietnam War.

As the point came where I had to have my trial, and I was expecting to be sent to jail, one of the professors whom I didn’t know personally approached me. He said he’d heard of this case and asked if I would mind if he spoke to the draft board; said he’d been on draft boards before and I think he was a veteran of World War II. I had no better ideas, so I said sure, and he spoke to them, and supposedly he convinced the draft board that I would really go to jail rather than acquiesce and go to war. He told them I’d be a pain in the ass for them, and they didn’t want that. They had a quota on conscientious objectors, but they also had a quota on people sent to jail, because that was very expensive for them. So, he told them also that I’d been invited to give some lectures in Europe, and he said, why don’t we figure something out here?

They allowed me to go to Europe: I went with a draft-deferment for “Services Essential to the Nation”, which was hilarious, because I was showing Flaming Creatures and Scorpio Rising and Andy Warhol’s films…they just wanted to get rid of me.

INTERVIEWER

You’re telling me the US Army — or rather, the Draft Board — agreed to send you to Europe to screen politically-subversive, homoerotically charged art films?

SITNEY

Exactly. And you know, as he pointed out to me, this Professor Herbert, largely these things are run by the secretaries. The draft board had denied me; they were horrible. The worst two people on the draft board were the priest and the rabbi — you know, the most gung-ho. At that point, I left graduate school, and I went off to Europe. When I came back, my wife — I got married as a sophomore because I hated the all-boy school feel of Yale — was pregnant, and I was immediately thrown out of the draft pool.

At that time, too, Anthology Film Archives had just been conceived, and I was made general director — a job which I was totally incapable of doing. And so, I spent two years setting up Anthology Film Archives and realizing my inability to be an administrator. Then I stepped down and became the director of library and publications. I did that for maybe three years. I was also invited to teach at Yale for a year part-time, which I did, and at Bard College, which I also did. Then I decided to go to graduate school to get a PhD, because I was interested in Paul de Man, who had then come to Yale. I went to graduate school while I was still working at Anthology. But then I was asked to teach full-time at NYU, and so I was full-time at Yale, at Anthology, and at NYU.

INTERVIEWER

So by the time you completed your doctorate, you had already started a family, you had already completed several lecture series in Europe, written a book, and worked two full-time jobs. This doesn’t sound like the average graduate student.

SITNEY

No.

INTERVIEWER

But when did you start with Anthology?

SITNEY

The idea of Anthology came about when two very rich men who had met each other in the Signal Corps in the Second World War (which is where a lot of intellectuals ended up) decided to put up some money. One of these men, Jerome Hill, had inherited the Northwest Railroad, the other, Burt Martinson, had owned what was the most successful quality coffee then marketed in New York — Martinson Coffee. Martinson was the bankroll behind Joseph Pabst’s theater, The Public Theater, and he was trying to get Hill to support Pabst’s theater. Jerome said, well, he would give a large chunk of money for a building if a film theater run by Jonas Mekas, Stan Brakhage, P. Adams Sitney, and Peter Kubelka could be in that building. So that’s how this came about. But I didn’t know about this at first, because this happened while I was off lecturing in Europe. I got a letter asking if I would be director of this thing. It hadn’t been built yet, and everything had to be planned, so I came back to do that. But I was by no means a good director.

INTERVIEWER

How did your relationship with your filmmaker colleagues develop? Were you already au fait with American avant-garde cinema and the filmmakers of the avant-garde?

SITNEY

Well, it was extremely lucky. When I was, say, 15 or 16, I got interested in cinema and couldn’t really see anything — we didn’t have anything like DVD around — and the only way to see any films was to form a film society and rent them. In order to form a film society I had to get other people involved. We convinced a local YMCA to let us use a room, we got about 25 people for a subscription, and we started showing classic films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Battleship Potemkin and the like, and also a few classic avant-garde films, which I thought were absolutely wonderful. Any time I could see an avant-garde film, I did. We had a series of notes for this society which we collated and called Filmwise. Somehow in the course of all this, when I was about 16, I met Stan Brakhage, who was in New York to show some films, and I arranged a showing of some of his films. When he sent me some writings he had done, I decided we should publish a big issue, around 30 pages, including his writings and writings on him. I put that together and put it out there, and went from there.

But I was very bold — I would write to people who were relatively famous asking if they would contribute, and some people actually did. I remember I asked Cocteau if he would draw the cover — and he did!

INTERVIEWER

Cocteau!

SITNEY

Yes! I asked Picasso once. I didn’t get an answer from him. But Anaïs Nin wrote regularly for us, and many others. People just responded — they didn’t know I was 16 years old. And then it turned out that when they found out that I was 16, they liked it even better! They thought that was really interesting, although I found it embarrassing.

After the third issue, Jonas Mekas of Film Culture[ref]Some archived materials from which are available here[/ref] asked me if I would consider joining and becoming an editor at Film Culture and publish the things I was collecting in there. When the American avant-garde film was getting a lot of attention, largely for spurious reasons — (because the Supreme Court made a decision that ended censorship of movies, to a point) I got a lot of attention. When I was a senior in high school, my mother got very frustrated, because people started calling and telegramming my home — the New York Times, Time Magazine, Newsweek — wanting to know about Andy Warhol’s films and about what Jack Smith was doing. Later, when no-one could take the first exhibition to Europe — Jonas Mekas was too busy to do it — I was asked to do it, and that’s how I caught some more attention. I had been writing about these films when no-one else was interested in them, so when the time came that people got interested, I had these files about all these films. It was just luck.

INTERVIEWER

How did this early contact with the avant-garde affect your intellectual interests? How did it help you develop as a thinker?

SITNEY

Well, when I was in high school, I was interested in poetry and literature, and I had a job at the hospital cleaning rat and pigeon cages, and feeding them. In retrospect, this was an amazing job: the doctors liked me, so they asked me to run their experiment on weekends because they wanted time off, but the experiment involved putting rats and pigeons in Skinner boxes and injecting them with LSD. I had a safe with thousands of little vials of LSD. It was ridiculous. (My experience with those animals left me with a life-long horror of recreational drugs.) In any case, I had gone to a kind of ghetto grammar school, and so I was very street-smart; so I put on my lab coat and I went over to the Sterling library and I said I needed a card. They asked where my ID was, I said I left it at the hospital, and they gave me a card, which didn’t let me take books out, but it let me go in to read whenever I wanted. There there were some texts by Maya Deren to read, some texts by Parker Tyler, lots of texts — I spent a ton of time at the Yale library reading about film.

INTERVIEWER

And did your filmmaker friends directly influence your reading habits?

SITNEY

Later, they did, yes. I was already hooked in. It was Brakhage more than anyone else — he had particular poets he liked and other things to recommend. But I began to meet a whole group of poets and filmmakers living in New York who all liked to recommend all sorts of things. I mean, by the time I was 19, I was deeply steeped in the tradition of Ezra Pound.

INTERVIEWER

It seems then these friends — these filmmakers and poets — were decisive in your intellectual life. That is very lucky.

SITNEY

Yes, and it also just happened to be a really great time to be there. It was before money hit the scene. Some painters were successful — but that meant that they had thousands and not millions of dollars. They didn’t cavort with rich people; they hung out in certain bars with each other, and many made almost nothing — but there wasn’t such a giant gap. It was before all the fashionable things that are associated with the Sixties and afterwards came on the scene; so it was a very very good time to be there. People were very very open.

INTERVIEWER

Is this scene, which you arrived upon mostly by chance, something which can be sought after today?

SITNEY

No, it can’t really be sought after. You just have to recognize something when it’s there.

INTERVIEWER

You don’t encourage your students to look for it? To look for fertile ground?

SITNEY

I do, but not directly and not in the traditional places. I encourage my students not to follow the traditional path of graduate school or business or whatever — I encourage them to go discover something. I have no idea what it is. I suspect that these days it must be locatable somewhere — the subcultures of the computer might offer that fertile ground. I can’t have anything to do with that now, but you can.

I’m quite sure, though, that the place to look isn’t in the world of art in the galleries, and it isn’t the world of film at Sundance or such places, but there must be some place where really interesting things are happening. One thing’s for certain though — you’re not going to find out about it in an Ivy-league school. Maybe not even in America — it might be somewhere else. I wonder what it’s like in Beijing or Manila right now?

INTERVIEWER

Why shouldn’t we bother with the “traditional institutional structures”?

SITNEY

When has anything exciting, anything truly new, ever been happening in the institutional structures? When have the universities, the museums, the mainstream publications — which are all highly problematic — ever been epicentres of anything great? I mean, if it’s in the New Yorker, then you have to wonder what’s wrong with it. John Ashbery is probably the greatest poet who’s ever been published in the New Yorker, but when I see his work there, I wonder what’s wrong! Where did John Ashbery go wrong that he’s now in the New Yorker? Is this just a function of old age? To be sure, the poetry there is by no means his best poetry, but still, what is he doing in a place like that? If a book gets reviewed in the New York Review of Books, I wonder what the author did wrong. Sometimes I think — oh, she looked liked an intelligent person, why is she there now?

INTERVIEWER

Well let’s turn to the University. You made a comment in a lecture not too long ago which I’d like to bring up now — you said that the university, Princeton in particular, is the great enemy of poetry. What do you mean by that?

SITNEY

Well first of all, it turns poetry into homework. This is its greatest sin. There’s nothing less sexy than doing your homework. You say: I’ll do a 100 lines of it now, and then I’ll do my chemistry, or whatever. That’s the enemy of poetry — it’s not leading where the poem leads. The temporality of writing and reading poetry is quite simply not the temporality of university life. And Princeton is especially a university of goody-goodies who like to do all their assigned work and get good grades and so on; there’s almost no room for deviation. There’s no room for fortuity, no room for searching, no room for serious things that don’t go on résumés.

INTERVIEWER

But if the temporality of poetry is not the temporality of the university then how by your reckoning can we come to the temporality of poetry? Where is it to be found?

SITNEY

There are poets to be found. And maybe you can find them in little magazines, maybe online now. Of course, in order to survive, these poets want jobs in the universities, but don’t fool yourself into thinking that because they’re hired by universities that the universities are places of poetry. Look where the poets are coming from. There was a period when people like Ashbery, James Merrill and Burroughs went to Harvard. They were all interesting; these were people, in the period I’m talking about, who were all gay at a time when it was difficult to be gay. Burroughs once said “the only thing I learned at Harvard was were to find the best boys in Morocco”. (Which I can believe!) But it was also a time when it was relatively easy for certain eccentric rich kids to get into Ivy League schools. They sort of clubbed together and weren’t concerned with anything to do with schoolwork and quickly found contacts outside of the university world. But that is now almost impossible at a place like Princeton or even at Harvard.

INTERVIEWER

Where would it then be possible?

SITNEY

I think it’s still quite possible in the cities. I mean, I am often quite enthused by the volunteers I sometimes see at Anthology Film Archives — there are very interesting young people from many parts of the world. They used to be all Americans, but now that Eastern Europe is so rich, you could, for example, be a Latvian druggist and find that it’s cheap enough for you to pay for a New York apartment to get your troublesome daughter out of Riga… or something like that. Anyway, these people see lots of interesting films, and some of them wander off and go make their own films, or some of them do other things — I see this all the time.

But I suppose you’re really asking about the culture. I think you need enough critical mass: first of all you need an empire, which draws people from all over the world, and you need twenty or thirty people, artists, real artists, who cross paths, I don’t know, once a week. They have to do certain things together and meet and discuss things, etc. Here, of course, I’d say that the great enemy of culture is the computer — because it keeps you off the street. In the days when there was real film culture, you’d be standing in line for a movie, and you’d see someone you saw at three or four other places, and sometimes you’d say, “Oh, how come I didn’t see you at the Japan Society for the Mizoguchi series?” And they’d respond: “Oh, I didn’t know there was a Mizoguchi series.” And you’d meet other people that way and you could be spontaneous and improvise what you would do. The computer regiments you and prevents you from creating an audience like that. But there are still places in some cities, like San Francisco or Los Angeles, New York or Boston, where people do see each other at poetry readings, at certain kinds of concerts, at film screenings, and that’s a place where culture happens.

INTERVIEWER

Am I hearing that you think culture and creativity happen where chance and spontaneity reign?

SITNEY

No, principally they flourish in imperial centers, where there are enough people drawn from all over the world, or the empire, because there’s cheap living! This used to be the case, for example, in the fifties — it was one of the great fortuitous things that middle-class people didn’t want to live in cities, and so the cities were the cheapest places to live.

My first place in New York City cost me $9 a week, and there was a place to eat where the cab drivers used to eat, the Belmore Cafeteria, and you could buy three vegetables for 45c — that’s 15c a vegetable. They had a selzter tap, and they had lemons, so you could make yourself a lemonade with free lemon, selzter, and sugar, and then you could sit all afternoon and talk, if you wanted. And rent was $10, $20, $30 per week at most, and there were various kinds of easy jobs here and there, because unemployment was low, and so the city drew people — you need this mixture of drawing people and easy economic survival.

INTERVIEWER

If cultural production flourishes in these places and does not flourish in the university, is that because of the inherent character of the university?

SITNEY

Absolutely.

INTERVIEWER

Has this to do with the characters of particular kinds of universities — does it make a difference if we’re talking about research universities or liberal arts colleges etc.?

SITNEY

It has to do with all of them, because it has to do with the regimented division of time that doesn’t allow you to really pursue something. The age segregation is another factor — since at college you’re largely people 18 to 28, all segregated among each other — and the transformation of creative energy into classes and into classwork — all of these things are deeply negative.

INTERVIEWER

So there’s subordination of energy and thought to particular ends which are not arrived at through creative searching or reflection, but are given, as if from on high. That reminds me of a comment made recently by Slavoj Žižek — what do you think of him, by the way?

SITNEY

I think he’s funny! Hilarious! I think he’s a stand-up comedian for the academic world.

INTERVIEWER

And God knows we need those…

SITNEY

Oh, but I think we have too many of them already. I mean, it’s actually the only way you get a job! If I weren’t funny, I certainly wouldn’t have a job.

INTERVIEWER

I doubt that’s only the reason for your employment.

In any case, Žižek complained in a recent talk that there is a notion becoming commonplace nowadays that the universities are factories for experts; places where people are trained to respond to the economically-defined demands and needs of societies. He has an anecdote to illustrate his point– supposedly, a French minister of culture once told him, years ago, in response to student riots in Paris, here we need intellectuals. We need psychologists who tell us how to control the mob, we need urbanists, who tell us how to restructure the suburbs, so that crowds can’t gather, and so on and so forth. Universities in this kind of environment should be factories of experts, whose job it is to subordinate their expertise and to train students to subordinate their faculties of reason to economically or politically pre-established goals.

When I heard Žižek complain about this, I thought, this sounds familiar– this is exactly how one understands the function of higher education where I’m from, in South Africa. But what about here? Does this complaint resonate with you?

SITNEY

I think that’s a description of a problem characteristic of European states. In America, private universities exist to train and produce affluent and generous alumni.

INTERVIEWER

Universities are not interested in producing intellectuals?

SITNEY

That’s beside the point — if they happen to be intellectuals, that’s fine, but first they have to be affluent and generous almuni. That’s what they take themselves to be producing.

INTERVIEWER

And if this is what they are doing, what should they be doing; is there another vision of the American academy possible?

SITNEY

They’re never going to change. It’s a perfect system — it’s working, and therefore there’s absolutely no motivation to change it. The universities are friendly to affluent alumni. They’re friendly to the project of turning out senators when they can. Of course, it’s still possible — they’re big enough for this to be possible — that students can still get a genuine education if they don’t listen to their peers or their academic advisors. In any of these universities there are at least a dozen really interesting professors, but they’re never in the same department, and one can knit together an education while everyone else is pursuing the trendy, the easy, and the conventional — the road to affluence.

INTERVIEWER

If the goal of the university is not to produce intellectuals, where does the intellectual find a definition of his or her task? Where, in your view, are intellectuals formed?

SITNEY

I don’t know. It does seem that no matter how strongly the forces of repression against intellectualism operate, some do emerge. But in America, there’s a very successful means of hiding them: the celebrity culture. All of the interests of the students and newspapers are with the celebrities; so, if an intellectual happens to be a celebrity, he’ll have an audience, but there’s no interest whatsoever in individuals who are not celebrities. This disguises whoever the real intellectuals are. And it also creates a spurious goal — it enshrines a false god — that propels many intellectuals to want to become celebrities.

INTERVIEWER

You see only a corruptive influence on intellectuals by capitalist and consumerist culture, then. Exactly what threats are posed to intellectualism and what difficulties created by the pressure to join part of consumerist culture?

SITNEY

I don’t really know how to answer that. There are fewer and fewer books that are not part of the market for university press books or intellectual books where credentialism is very important. So it’s harder to find independent thinkers. But there must be places where they find to be printed or published. On the internet, maybe — I don’t know. I’m too old to know.

INTERVIEWER

But then that phrase — independent thinker — what does it mean?

SITNEY

Well I’m thinking of someone like Norman O. Brown, who was very interesting in the Fifties and early Sixties, or Kenneth Burke, in the Thirties and Forties. These were people who were not necessarily artists, but who somehow managed through teaching or writing to eke out some kind of limited living and yet had a limited following from their publications without becoming celebrities. They were neither artists nor celebrities, but they wrote books and thought about things. Many of them had artist friends or worked with artists; often they wrote criticism of people in the arts, or were read by them — they lived in interaction with those communities, but now it seems that the world of the arts is very often contaminated by and corrupted by the academic world. Communities of painters and sculptors publish magazines that write only about people like Žižek and Derrida; it’s obviously a very decadent culture, and it coincides with the collapse of the vitality of American visual arts.

INTERVIEWER

The visual arts have collapsed in America? When did this happen?

SITNEY

Yes! It started in the Seventies when money erupted into the scene. In the wake of that, we have academicism. We’re in a deeply academic period in American art right now. It was the same thing when French painting had turned academic, and then it took people another 30 years to realize that there were the impressionists operating at the same time, but they were getting refused from the salons and the public shows. I think there’s probably something going on, but I wouldn’t know about it because of this deep academicism that we’re embroiled in.

INTERVIEWER

Academicism is the enemy of innovation. But when you speak of vitality, are you speaking of the new? How do you understand “vitality” in the visual arts?

SITNEY

I guess it means that there is a sense that there are individuals creating original work and that there are others who are drawn to it and contribute to it in some way; that this occurs outside of the official institutions, either because they are seen as threatening to institutions or because they are called ludicrous or humiliated. This phenomenon tends to have geographical shifts — it tends not to emerge in the place where it was last dominant. I suspect it wouldn’t be in New York, but I don’t know what it’s like in Tokyo or Istanbul, etc.

INTERVIEWER

So for you “vitality” has to do with the cultural matrix in which artistic production occurs. As you discuss the matrix which you perceive as being responsible for the degradation of the visual arts in America, and its link to capitalist culture, I’m reminded of a early passage from your book Modernist Montage:

Cultural modernity reflects the Protestant spirit in the arts. The gradual interiorization of Luther’s theology and Descartes’ philosophical independence culminated in the modern paradox of Kant’s formulation of the mark of an aesthetic object: “purposiveness without a purpose” [Zweckmäßigkeit ohne Zweck]. He recognized that aesthetic experience was at once radically subjective and fiercely committed to an ideal of universal assent. In essence, it duplicated the structure of Protestant conviction without reference to a God.

The aesthetics of Protestantism diverges from its economics, if we follow the classical argument of Max Weber. Weber saw the religious notion of a “calling” leading to the secular pursuit of a life of productive work, even while the religious motives were evaporating; but in modernist aesthetics the ancient idea of a poetic calling was revived and re-formulated with an intensity that actually increased inversely as the theology of election ceased to matter in the accumulation of wealth. Without upholding the religious tenets of modern Christianity, the modern artist came more and more to oppose the commercialism of a society that increasingly displaced a theological notion of human labor onto objects for sale. Therefore, in opposition to the manufacturer, the artist tended to treat his of her works as sources of aesthetic revelation rather than as products for use and profit. [ref]Modernist Montage, p3.[/ref]

SITNEY

Well that’s pretty good! That’s from when I used to be good, before I became decadent myself.

INTERVIEWER

I’d agree that’s pretty damn good! But I’m curious about this last sentence — “therefore in opposition to the manufacturer, the artist tended to treat his or her works as sources of revelation rather than as products for use and profit” —

SITNEY

Yeah, if you stop for a second and look at the people in my department [Visual Arts], they are exactly committed to the opposite of that idea of art. There’s in the art world in America now a deep hatred of the idea of originality and inspiration, a deep hatred of revelation. There’s some ridiculous notion that art can be democratic. Art is the least democratic of all things!

INTERVIEWER

What do you mean?

SITNEY

Oh they want to make sure that there’s the right Chicano artist, and that there’s gender equality, and that this and that other political requirement is met. God knows, it doesn’t work that way! I mean, inspiration doesn’t fall democratically! The poetic calling is not a democratic thing; it’s indifferent to it. So the way in which people get around that is by claiming that there’s no such thing as a poetic calling; it’s a culturally-manufactured category and who knows what else. But this view leads unquestionably to a kind of radical post-modernism in which you’re not supposed to recognize the quality of a work of art, or the individuality. It’s all about some negotiation on the market. So you get the glorification we see now of an abomination like Jeff Koons!

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that modernism has ended in all domains of the arts, or only in the visual arts?

SITNEY

Modernism still? I don’t know. I pay attention to very few people who are pre-menopausal, so I don’t know what the twenty-year-olds or even the thirty-year-olds are achieving. I would think that surely it’s possible. But at this point I have to say that I am a thoroughly academic creature; in speaking of this modernism I am speaking of something which I admire, but I have massively sold-out to the academic world. I earn my living as a professor and I’m as professorial as they come.

I admire enormously someone like Eliot Weinberger — who dropped out Yale after his freshman year and he began to write on art and politics completely independently and he’d have nothing to do with the academic world. This is genuinely admirable.

INTERVIEWER

So who sets a better example for your students: you or Weinberger?

SITNEY

I haven’t really been encouraging my students to follow the example of a Weinberger — that would take a lot more balls than I have, and certainly more than I would expect most students to have. But it’s wonderful that such people do emerge, and that places like New Directions publish him. I don’t share his radical leftistism — he calls himself “just a plain old New Dealer/Euro-socialist” — but I think his writing on poetry is excellent and its inseparable from his political vision.

INTERVIEWER

Purposiveness without purpose — what does that describe? Is that a description only of art-works and artistic thinking?

SITNEY

I can’t think of it having anything to do with anything but the autonomy of the art work, and the sense of a transcendental goal which isn’t a goal.

INTERVIEWER

This is completely discouraged by the institutions of capital?

SITNEY

You’ve sort of politicized and economized it. Capital is a very subtle thing. I’ve seen in my own lifetime how institutions have arisen to make a lot of money for people who didn’t think they had an interest in making money, who wanted nothing to do with money. I remember Warhol gave us one of his Liz Taylor paintings to help pay for one of my lecture tours, and we probably got about two or three thousand dollars for it. Now, it would probably go for about five million.

So somewhere along the line, some people have figured out how to turn that piece of canvas into real capital. Manuscripts of books and poems that no-one would publish before go out on auction now for tremendous prices. So capital is very subtle. And supple. So I wouldn’t blame capital for anything; if someone figures out a way to make money on something, they’ll do it. All our most recent heroes are these people — look just at Princeton. E-Bay and Amazon are perfect products of the Princeton education system: a way to make money on other people’s stuff. And God bless them for it! I’m not opposed to capital, I’m opposed to the false idols which have perverted so many people.

I’ll give an example. I have a friend who’s a poet, and I met her when she came to give a course at Princeton, which I never expected she’d do. Susan Howe — I’d been reading her for years. She came here because a member of our faculty — Susan Stewart — has power in the English department and can recommend people to do special one-semester courses. So she came and I asked if I could sit in on her course, and we became very good friends afterward. She’s a completely original, wonderful woman; never went to college, although her father was a professor at Harvard Law School, and her mother director of the poet’s theater there. She tried being an artist, but she really became a highly original poet. When she needed money, she was teaching in a program at Buffalo. We have terrible arguments, because she somehow has it in her head that people like Derrida and the like are really, really important, although she confesses she doesn’t understand them. But it’s really important, she says, to try to understand them. This is really where things are. She loves prestige prizes which I despise, and it bothers her who gets a Pulitzer or whatever — whereas I think that’s a complete waste of time, if you get a Pulitzer, I ask what you’ve done wrong! —

INTERVIEWER

Like the New Yorker?

SITNEY

Yes, and she complains about who gets published in the New Yorker too! But it’s bizarre — she’s the most perfect example I know of the kind of originality and education I spoke of. And she does lots of very interesting research — she was an incredibly original reader of Emily Dickinson and so on. But she believes in the artistic value of what’s in Artforum — for which I too write, hypocrite that I am — or in what’s at the Whitney. All these things matter to her, although she is a perfect example of the opposite of what they embody. Anyway, I mean to say that it isn’t as if I’m the voice of a particular position, I just have my own personal experience in the world, and I contend with my loathing for the conventional ideals of the university. And I suppose I could be accused of biting the hand that feeds me. I’m certainly grateful for the position I do have, but I also know that every university needs, almost as part of its decoration, a weirdo nay-sayer or two, as long as they’re impotent. That could be the title of your article — the impotent decoration!