From Province to Province: Alan Lomax and the Folk Music of Old

“Dante was once ten years old. He was a remarkable child. He babbled sonnets and rondeaux which revealed his nature. Do you put the prattlings he produced at ten before the ‘Divina Commedia’ he composed at fifty? If you are the usual folk-art worshiper, why not? Were those lyric works of Dante’s youth not the pure Dante? the untrammeled sign and substance of his soul? Were they not Dante’s folk art?” — Waldo Frank

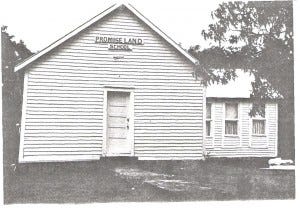

The image that I’ve seen of Theo Edmondson and the Promise Land Singers may be the only one left. It’s certainly the one easiest to excavate without having to bother a distant relative or an alert scholar of Tennessee regional music history. In the picture, they must be in a house, the St. John Promise Land Church (the second iteration; lightning felled the first) or, maybe, the Promise Land School (another derivative, for the original burned in the late 19th century). Theo, probably in his forties, does not look like the man who built my grandfather’s childhood shack. I am sure that two of the girls surrounding him are my great-aunts, or their mothers. The school closed in 1956, but every year a committee gathers to organize local festivals and a family reunion. I haven’t been for many years, but in photographs I see new, young faces. I register absences and transformations.

Among the earliest settlers of the community were freedmen with names that have acquired the tinge of royalty, though they are plain: Nathan Bowen, Joe Washington Vanleer, Charles Redden, John Grimes, Jerry Robertson. Their surnames are those of ironmasters and industrial slave-owners. Having served in colored regiments during the Civil War, Arch and John Nesbitt, soldiers like Remus and Romulus, used their pensions to found their land upon a plain. By 1880, at least 175 people called it home. I have played games imagining where these homes may have stood. There were several stores, too, like Jumping Jim’s Place — formerly the Old Grocery Store owned by John Wesley and Emma Edmondson. If it stands now, it is a disemboweled hut surrounded by trees. A sign in front of the school declares this hamlet worthy of inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. It is a dubious honor, similar to when one says, “People from other countries visit here,” and no one can say who they are. The sign does not explain the origin of the name. Promise Land. Are its heirs the unlisted beneficiaries of that covenant made with Abraham?

Go, walk through the length and breadth of the land, for I am giving it to you. — Gen. 13:17

Some surmise that the name represents the federal government’s promise during Reconstruction to set aside this rich land for its black inheritors. We know only that it denotes a pre-industrial condition, when the North had not yet contrived to become the black Mecca.

Today, Serina Gilbert — a distant cousin of mine — runs the Promise Land Community Center and a humble historical display named after my grandfather. My father and various others are trying to get a paved road built through the town. My father says, let my generation one day take ownership of the place. Visit often. Follow the path that takes you to a family cemetery. Help beautify it. Read the names on the slabs or crosses you find, and do not tread on the graves. Imagine if there were a grocery store or library here, or if it were a summer resort like Idlewild in the nexus of its youth. I have trouble doing so. I first want to remember how Theo Edmondson and his singers sounded. I contacted the radio station on which they were frequent guests in the 50s, asking to hear some of their gospel songs. I have not heard back.

***

“[T]he days of singing freedom songs and days of combating bullets and billyclubs with love are over. ‘We Shall Overcome’ sounds old and dated. Man, the people are too busy getting ready to fight to bother with singing anymore.” — Julius Lester

When Alan Lomax was Assistant-in-Charge for the Library of Congress’s Archive of American Folk-Song in 1938, he thought what a fruitful trip could be had in the Upper Midwest. The Texan was 23 years old, and he was given a couple of months and a little under one-thousand dollars to collect songs, stories, and whatever miscellany he wished to record. There had been ambitious American folk music collectors before — Lawrence Gellert, David Kohn, and Robert Gordon are among the better known — but small, Midwestern communities still occupied that liminal space between the arcane and the intelligible. Lomax went up in an old Plymouth DeLuxe with a newly-furnished Presto recording machine and a couple of cameras. When he went to Michigan, soon after recording Hungarian folksingers in the Delray neighborhood of Detroit, someone broke into his car and stole the Presto’s recording head. The next day, the machine itself and Alan’s guitar were pilfered. He had no choice but to request another machine from Washington, and after a week, he got it. He would remember the Serbian workers that sang for him and played the diple in the shadow of a Chrysler plant, the vibrant Irish enclave on Beaver Island, the Finnish miners of the Upper Peninsula’s “Copper County,” the Saginaw-based lumberjacks telling stories of Paul Bunyan and his blue ox. In all, he recorded ten acetate discs of logging songs, sea shanties, and European ballads. He had six linear inches of notes, eight reels of film, and some photos. After leaving Michigan, he wanted immediately to return.

During his last trip to the state in November 1938 he met up with bluesmen Calvin Frazier and Sampson Pittman. Lomax suspected they must have been close to the man he was really looking for, master guitarist of the Delta blues Robert Johnson. But the search failed, and Lomax instead recorded a few songs with the Detroit-based musicians. Pittman’s voice allowed no easy trespass into his songs, encoded as they were with frustration at the welfare state, work in southern levee camps, and adulterous women. He memorialized Joe Louis in an eponymously-titled song,

[audio http://cdn.loc.gov/master/afc/afc1939007/afc1939007_afs02476a.wav ]

warning his opponents to leave the ring while they had a chance, and he wrote about the legendary U.S. Route 61 (Bob Dylan had some years yet before he’d release Highway 61 Revisited). The recordings are imperfect — the tracks will skip and scratch — and the voices transfer as though through wire mesh. Their style of guitar-picking may be a spiritual guide to the likes of John Fahey’s 1965 release, The Dance of Death & Other Plantation Favorites.

Until the end of his life, Alan wore the steady, decontextualized expression of an impenitent child. He was never winsome until laughter broke a heedful gaze, and one who did not know him might have misinterpreted his stocky frame as vaguely threatening. Such judgment would have been ill-formed. Alan’s down-home drawl was deliberate and effete, at odds with an overwhelmingly casual wardrobe. One might not have ascribed to him the qualities of a cultural gatekeeper until he began to speak, rapidly and with cultivated elegance. I had heard of Lomax before — he was a stranger whose face I recognized only upon inspection — but I re-encountered him after searching for prison work songs and finding one holler he recorded called “Rosie.” This, in turn, led me to the massive online archive documenting Lomax’s career from 1946 into the 1990s. It would be easier to describe what the archive lacks rather than what it contains, for there are thousands of audio and photograph files, dozens of videos, radio programs, lectures, and more. In the months spent exploring the archive, I managed to comb but a fraction.

***

“Melody lay on his back, guitar across his chest. Every now and then his hands started idly over the strings but they did not find much music. He didn’t try any slicking. That was for back home and the distances in the hills.” — William Attaway, Blood on the Forge

In 1909, Alan’s father, John Avery Lomax — who grew up listening to cowhands croon on the Chisholm Trail — convinced a group of friends from Austin to form the Texas Folklore Society, which would be responsible for gathering local folktales and music. While serving as registar of UT-Austin, John had made friends at Harvard who were interested in folklore as well, and venues across the nation invited him to recite country poetry and sing ranch ditties. In 1910, he published Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, dedicated to and introduced by Theodore Roosevelt. The former president praised John’s collection for preserving “permanently this unwritten ballad literature of the back country and the frontier.” The public, wrote Harvard professor Barrett Wendell in the preface, would forgive the “artless” and “unsophisticated” tunes if only because they were supremely true. Where beauty and grace withered, the genuine American spirit would surge forth. If any aesthetic quality could be attributed to this music, it was only an acknowledgement of folk’s potential to become greater, the rudimentary material from which a fine Occidental art could emerge, properly sculpted.

Historically, folk art has denoted those works produced outside formal institutions and which were, in some places, responsible for the social organization of a community. Many folk artists were (and continue to be) self-taught, often prospering in small, scattered communities. When we speak of the early American folk artists, often we indicate the legion nameless, the rural laborers who turned out quilts, hooked rugs, spinning tops, gameboards, wood carvings — the art brut of human marginalia. Wendell’s rhetoric indulges in negative formulations of folk art as amateurish. It is the dull speech of one who can only interpret the carefully rendered pastoralism of Thomas Cole or the spectacle of Saint-Gauden’s Civil War monuments.

The boy Alan arrived at the start of 1915. When John was offered work as a bond salesman in Illinois, the Lomaxes moved to a two-story sandstone building in Highland Park. Though Alan excelled in school, he was always a sick child. His illnesses would recur throughout his life, and frequent infections would eventually render him deaf in one ear. John began sending Alan to the ranch of family friends near Comance, TX when he was ten, where he was expected to foster his own intellectual and physical welfare through reading and ranchwork. Though Alan would participate in sports while attending the Choate School in Connecticut (a feeder into Harvard), he couldn’t mask his disdain for the strenuous life. He much preferred studying European girls and Nietzschean philosophy, drinking water instead of wine. When the Depression hit, John lost his job and Alan’s grades worsened. Their relationship, a seemingly unfulfillable contract between son and father, may have fallen into a historical darkness had Alan not agreed to accompany John on a recording trip through the South. John was to compile an anthology of folksongs for Macmillan, and he offered to help the Library of Congress expand their nascent folk collection if they would help him secure grants.

With little money and a Model A packed with two army cots, bedding, camping gear, and clothes, John and Alan set off across Texas, heading north toward Kentucky. They spent their days among black populations, mostly, camping out at night or renting cheap hotel rooms. They refused to approach their encounters professorially. If they could avoid arrest by white officers and overcome the skepticism of their black acquaintances, they would linger in any given location and learn about life there before asking anyone for songs. In Dallas, they bought an Ediphone — a 315-pound disc-cutting recorder — that could capture voices, although the playback was faint and would need to be transferred from cylinders to discs. Alan recalls a black washerwoman who sang into the machine for them:

The voice of the skinny little black woman was as full of the shakes and quavers as a Southern river is full of bends and bayous. She started slow and sweet, but as the needle scratched her song on the whirling wax cylinder, she sang faster and with more and more drive.

Alan seemed to privilege the recorder as an extension of the field collector that served as a fluid, two-way channel between the folk and the machine. Standard written notation of words and melodies couldn’t represent the “myriad-voiced reality” of folksongs, and in the worst case may have deprived the songs of their potency. Only the recorder could capture “the subtle inflections, the melodies, the pauses that comprise the emotional meaning of speech.”

Near Huntsville, Alabama, John and Alan met a man named Blue in a schoolhouse lit by a single oil-lamp. Black tenant farmers had gathered there to sing spirituals for the Lomaxes (at the behest of the plantation manager), and when Alan asked if anyone knew the original words to “Stagolee,”[ref] “Stagolee (Stackerlee) by W.D. Stewart”[/ref] Blue stepped up and cried a plaintive song of a downtrodden farmer. Afterwards, with the other farmers laughing, Blue made an appeal into the recording machine, asking Franklin Roosevelt to help poor southern Negroes like him prosper in life. Though the crowd was raucous, Alan received this request solemnly. He would write, “I saw what I had to do. My job was to try and get as much of these views, these feelings, this unheard majesty onto the center of the stage.” Lomax would later refine his articulation of purpose:

We propose to go where…Negroes are almost entirely isolated from the whites, dependent upon the resources of their own group for amusement; where they are not only preserving a great body of traditional songs but are also creating new songs in the same idiom. These songs are, more often than not, epic summaries of the attitudes, mores, institutions, and situations of the great proletarian population who have helped to make the South culturally and economically.

The Lomaxes would continue on, stopping at Imperial State Prison Farm outside Houston. There they met Mose “Clear Rock” Pratt (a 71-year old imprisoned for stoning three people to death), James “Iron Head” Baker (whom John christened Black Homer), and Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter (whose “Goodnight, Irene” would later be hailed as a folk standard). They sang of trains, baying dogs, cowboys, boll weevils, heat and dust. These “made-up” songs were not entirely so. Much like the “lies” that Zora Neale Hurston would record in Mules and Men, her impressive document of southern black folk legends, these songs came from a protracted history of social and political repression. When black protestation could not find approved outlets — vocal opposition often leading to predictably violent consequences — slaves, sharecroppers, and factory workers crafted tales and songs inscribed with their discontent. Under what circumstances these stories originated is impossible to determine, as these epics and ballads were gifts of speech and not of transcription. Joel Chandler Harris’ Uncle Remus stories helped popularize black folktales of duplicitous animals, perhaps themselves influenced by legends of the great trickster figure, High John the Conquerer. Lomax, writing about the transference of folksongs, said, “[i]f they touched something universally true in [the folksinger’s] culture and served as a means of communication between singer and audience, they were repeated.” Like members of a medieval cult of saints, these black bards encased their heroes in glass through processes of preservation and fabrication. Purposeful lapses in memory enabled the black creator to subtly alter the landscape of an ancient song. One stanza might be transfigured or entirely cut to suit the speaker’s preferences. As the nation’s social and political climate changed, each new generation of workers could contribute its own time- and place-sensitive repertoire. The black creator was at once improvisatory and tradition-bound in his tendency to contrive legends that would appeal to the greatest number of people. This was not the doubtful charity of a popular artist who takes only his audience’s happiness as payment, but of a simultaneously generous and selfish dealer who shares his art that the community will affirm his trials and society begin to comprehend them.

Alan and John returned to Washington triumphantly, and John became Honorary Conservator of Our Archive of American Folk-Song. Macmillan greeted American Ballads and Folk Songs with fanfare, and this would be the first of a few collaborations between father and son. Louisiana welcomed them next, and they observed with some chagrin that many musicians were transitioning toward country and western swing — dancehall music. After Alan’s next project — a collecting trip in Florida alongside Zora Neale Hurston — he fell in with the New York Bohemia scene, enticed by the likes of e.e. cummings, Edmund Wilson, and Djuna Barnes. There he met Elizabeth Harold Goodman, a young liberal poet of whom John disapproved (Elizabeth had a child in high school, which must’ve chafed John’s rugged, conservative backside). They would eventually marry while Alan and Hurston conducted fieldwork in Haiti, recording Vodou and work songs, tales of the undead, and syncretic spiritual ceremonies.

In his new position as a clerk in the Archive of American Folk-Song, Alan tracked the growing national interest in folklore, receiving letters from artists, Hollywood producers, and educational groups. The New Deal, with its emphasis on economic democracy and community-building as penance for selfish corporate practices, sought to invigorate the nation one region at a time. Initiatives like the WPA Federal Arts Project and the Treasury Section of Fine Arts were viewed by some as direct responses to the museum culture upheld by industrial magnates. These projects were to reshuffle the cards of creative monopoly, placing the American artist in communion with the public. By the end of the fiscal year 1938, the archive had received more than 1,500 discs, significantly more than the 1,300 they had collected in the previous ten years combined. Davidson Taylor, supervisor of the CBS workshop, approached Alan with a proposal: he’d be given a team of writers, actors, producers, an orchestra, and educational directors to make 25 weekly folk music programs for American School of the Air. Each would discuss a different social theme. Initially, radio repelled Alan, but here was a chance to choose his guests from the hundreds of musicians he’d encountered, pay them for services rendered, and expose young listeners to the rich peripheral communities of the country. Alan heralded the democratic potential of regional music. The nation, newly girdled with a string of diverse, sometimes politically-incisive tunes, could take an important step on the long road towards social liberalism. As Lomax’s biographer John Szwed writes in The Man Who Recorded the World, “Art…was now the basis of a crusade for justice and cultural equality.”

The nation’s unprecedented New Deal advocacy of local culture, which for Alan constituted the “total accumulation of man’s fantasy and wisdom,” regardless of its political currency, is unlikely to happen again. Lomax’s conception of the folk as something that incubates in one’s own backyard, in the warbling throats of a black or Yiddish grandmother, or in the one-stringed vihuela of the ancient Spanish minstrel, has perished. For this we may cite changing musical forms (e.g. spirituals to modern gospel), popular adaptations of folk songs (e.g. Ram Jam’s appropriation of James Baker’s “Black Betty”), digitally-facilitated access to folk material (easy access dismantles illusions of rarity or exclusivity and encourages adaptation), and the natural death of those generations for whom these narratives were most relevant. This matter of appropriation, noted often in discussions about artists like Elvis Presley or virtually any band of the British Invasion, is troublesome and has long since voided obvious avenues to folk preservation. Today, to preserve the folk is to maintain the élan vital of certain constructed historical memories, whose catalysts no longer exist in their purest forms. For a black singer to assume the perspective of a sawmill worker traveling from levee camp to levee camp is absurdly dishonest if taken in earnest, for it is an impossible conditional. The anachronicity of the occasion, coupled with disparities between the singer and the subject (gender, class, race), may encourage laughter or even disapproval.

***

Author Jean Toomer predicted a century ago that, if the black folksinger survived today, he would live in art. We find this explicitly expressed in Corey Barksdale’s 2012 exhibit, The Art of Transition. Barksdale is an Atlanta-based visual artist who makes kaleidoscopic acrylic and aerosol portraits of black musicians, the Apollonian children of the Black Belt and the great northern diaspora. A contemporary band like the Carolina Chocolate Drops muddies the Lomaxian-purist vision of whatever is acceptably “folk.” This young African-American string band — currently consisting of frontswoman Rhiannon Giddens, cellist Malcolm Parson, and multi-instrumentalists Hubby Jenkins and Rowan Corbett — matured under the aegis of legendary folk fiddler Joe Thompson (one of three brothers who Lomax would include in his 1990 American Patchwork documentary film series). Until his death in 2012, Thompson represented the enduring legacy of a musical tradition that predated country music and bluegrass — the black string band.

Giddens mentions mandolinist and fiddler Howard Armstrong (whose Tennessee Chocolate Drops gave co-founders Giddens and Dom Flemons their namesake) as another central influence on the band’s style. The tongue-in-cheek title of their Grammy-winning album, Genuine Negro Jig, treats as negligible Gidden’s own classical upbringing. Their live performances and music videos are replete with flatfoot dancing, jug-slapping, kazoo-blowing, instrument-swapping — what Rolling Stone calls the “dirt-floor dance electricity” of their tunes. But, in Leaving Eden (2012), the band has also reconciled the voice of a thirty-something soul singer reminiscent of Dinah Washington (“Ruby, Are You Mad at Your Man?”), the spirit of North Mississippi Hill Country fife-and-drum bands (the ghosts of Napoleon Strickland and Othar Turner haunt “Riro’s House”), and in some performances, beatboxing reminiscent of early hip-hop (courtesy of occasional accompanist Adam Matta). The Carolina Chocolate Drops’ website contains the disclaimer: Yes, banjos and black string musicians first got here on slave ships, but now this is everyone’s music. It’s okay to mix it up and go where the spirit moves.

It is unclear whether this band may at will relinquish such a broad inheritance on behalf of thousands whose predecessors wouldn’t have ceded their music. What the band truly blesses is the catholic vox humana (“human voice”), an edifying alternative to the dangerous niche game of provincial folk recreation. One can engage safely with the folk so long as it doesn’t partition itself from other, nicer children. The folk that can behave civilly (mixing liberally with other musical forms) without entirely denouncing its origins might even hope to survive. It is the conjure that paints slight mutilation with a velveteen voice, a deliberately tipped fedora, and cover designs resembling any of the old Folkways Records albums. The “genuine” negro jig succeeds as a simulacrum, and is the eloquent valediction delivered at the Folksinger’s behest. Each swinging ditty stirs the Folksinger’s urn, and in the blindness of skillful mimicry, our eyes believe his ashes have spilled past the brim and changed into the living dead. And it is no fault of the band. Or it is their fault only so much as they can be blamed for emulating musicians they admire. For the enthusiastic root revivalist, they are godsends. I am not a miserly gatekeeper of black folk musical practices, but I wonder at what point language should shift to accommodate the thing denoted. There is no satisfying vocabularly with which to distinguish the shibboleths of traditional black folk and this contemporary offshoot. One cannot even call it neo-folk, as that already connotes distinctly European characteristics.

In his review of the 1982 exhibition, “Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980,” Eugene Metcalf called folk art one “in which the tension between personal freedom and social restraints often give meaning and power to artistic expression.” Black artists during the Harlem Renaissance were caught in the vortex of white consumer interest, and many felt that folk practices embodied an undisciplined, simple past.

Rare were the people like Jean Toomer, whose seminal work, Cane, was written as a death knell for the “folk-spirit.” In accordance with Metcalf’s interpretation, I don’t believe we can talk seriously about black folk music without allowing for its explicitly social function. Critique is its birthright, and no wonder someone like Lomax wanted to exploit its power throughout the Civil Rights Movement. Guy Carawan, long-time friend of Lomax and the musician best known for establishing “We Shall Overcome” as the movement’s anthem, drew on black religious and folk standards to create the freedom song, which did not sacrifice cultural authenticity for ethical steadfastness. Recognizing his status as a white participant of the movement, Carawan thought it best to conduct workshops and teach songs to picket-line protestors rather than lead them. He was what one might call a proper ally.

The most popular tunes of the freedom repertoire consisted of “zipper songs,” which had short, repetitive verses that could be easily modified for specific occasions. “We Are Soldiers,” “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Round,” “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize”– they were the progeny of interracial activism, and Carawan invited Lomax to his third “Sing for Freedom: Festival of Negro Folk Music and Freedom Songs,” held at a former plantation in Edwards, Mississippi in 1965. “Resource people” like Lomax, the Georgia Island Sea Singers, and the Moving Star Hall Singers discussed ways to preserve black traditions by integrating them into the most recent freedom struggle. Soon after Michael Brown’s death, creative members of the St. Louis community were releasing poems, art, short films, and commemorative songs on SoundCloud and other sites. One of rapper J. Cole’s lyrics in “Be Free” goes, I’m letting you know, that they ain’t no gun they make that can kill my soul. With what ease I could transpose this into a protest song from Coahoma County at almost any point in the 20th century. Rap group Souls of Liberty wrote “Stay Alive” two days after Brown died. Their verse, I don’t really feel like the answer is getting baptized/I don’t really fuck with Al Sharpton and his damn lies points to a motif of African-American discourse that became prominent in the late-twentieth century: the transfer of black outcry to more politically effectual outlets than spirituality. Hip-hop’s emergence as that alternative seemed especially feasible with the release of a track like N.W.A.’s “Fuck tha Police,” which rejected the niceties of accommodationism. The song was both prophetic and diagnostic, but that type of politically potent rap song is generally unwanted today, partly because we are more skeptical of art as socially constructive. And anyways, most of the genre’s mainstream channels are in no state to communicate much beyond beats and bedazzled backup dancers. If folk is dead — and I believe at least the substance for its proper rejuvenation survives in this contemporary ongoing movement — then neither has hip-hop lived to fulfill what once seemed an inevitable destiny.

***

As early as the late 50s, after returning from a nine-year European recording trip (which merits a retrospective of its own), Lomax himself figured in the American chapter of “folk revival.” Earlier that decade, in New York, he had organized and emceed a successful concert for People’s Songs (music by and for American laborers and progressives). The event was such a hit that Alan received sponsorship for his Midnight Series. “Honkytonk Blues at Midnight” is probably the most historic, as it featured Big Bill Broonzy, Memphis Slim, and Sonny Boy[ref] “Conversation with Big Bill Broonzy, Memphis Slim, and Sonny Boy Williamson about the origins of the blues”[/ref] — each of whom would become some of the most influential blues players in the states. And we are lucky that Alan traipsed through this scene, placing blood and bone of the South into the immense music halls of cities. He had wanted truly to become a writer of the common man, a Faulkner or Dos Passos who could justify the ways of tracklayers, sawyers, and pastors to the literati. Despite winning the 1993 National Book Critics Circle Award for The Land Where the Blues Began, the account of his 1973 collaboration with Fisk University professors to sketch a biography of the Delta blues, Lomax would always disparage his writing as mediocre.

When he returned from Europe, Alan had discovered the changing face of music. Rock ’n’ roll and Johnny Lee Hooker’s brand of the blues began subsuming traditional folk artists. At Carnegie Hall in April 1959, Lomax staged “Folklore 59,” which focused on music from small southern towns (including a relatively new type of music, bluegrass) to urbanized bands and popular singers like Ray Charles, Fats Domino, Bobby Darin, and the Everly Brothers. Alan’s assistant in 1961 had a sister who lived with Bob Dylan, so he sometimes came by Alan’s New York apartment, cramped as it was with books, records and coffee cups, and met the very artists that would influence him and others like him throughout the 60s. In 1964, Lomax would help organize the extant Newport Folk Festival, bringing together singers he’d encountered from America and Europe. There were cowboys, Cajun musicians, panpipe players. Joan Baez, Dylan, Canray Fontenot[ref] “Bonsoir, Moreau by Bois Sec (accordion), Canray Fontenot (fiddle, vocal)”[/ref], and Johnny Cash. By the next year, however, a diluted folk-rock subgenre was developing and the festival’s organizing board had to contend with increasing performance and administrative costs. When his interest in the Newport scene waned, Alan hopped over to D.C., where he and his younger sister, Bess, would play a central role in the Smithsonian’s annual folk festival. He organized “An American Folk Concert” in 1973, and three years later, Congress fortuitously passed the American Folklife Preservation Act, which created the Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center.

Lomax whetted his philosophy of cultural equity in his encounters with Congressional representatives, culminating in his 1985 “Appeal for Cultural Equity.” Lomax augured the decline of a human cultural biosphere:

A grey-out is in progress which, if it continues unchecked, will fill our human skies with smog of the phony and cut the families of men off from a vision of their own cultural constellations. A mismanaged, over-centralized electronic communication system is imposing a few standardized, mass-produced, and cheapened cultures everywhere.

A non-believer in the linear “progress” of industrial and capitalistic systems, Lomax warned against the apathetic observer content to watch as tribal processions, local festivals, and folk practices perished on the modern desert. Such passivity was anti-humanist and an example of “false Darwinism applied to culture.” The doctrine declared the “equally expressive and equally communicative” nature of all musics, as members of each culture interacted according to their own social mores. During his European tour, Lomax had introduced controversial methods of tracing communities’ social organizational patterns through their various forms of musical expression. As measurements of verbal expression patterns, cantometrics (song styles) and parlametrics (conversational styles) complemented studies of non-verbal interactions — choreometrics (movement patterns). Criticized for employing Eurocentric measurement values, Lomax’s quasi-science nonetheless buttressed his emotional appeal for the recognition of all musical styles as uniformly valuable. The death of any one of these was a tragedy as grave as losing an animal species. Without cultural justice, certain musical “zones” would become inhospitable.

Lomax’s utopic phase would grow from paltry soil. The rise of electronic communication systems was not injurious of itself, but the mercantile companies that governed its usage destroyed a two-way feedback system in favor of a homogenous center. To preserve and reclaim ownership of cultural landscapes, an electronic system that “could carry every expressive dialect and language that we know of” was needed. Lomax’s Global Jukebox, a paradigm of folksonomy, implicated a turn to transhumanist themes. The Global Jukebox was intended to “describe, map, classify and interpret orally transmitted performance traditions from all world regions.” Using a large menu and an interactive, virtual globe, the user would navigate thousands of sound and video clips, images, and texts to learn about the aesthetics of cultures across time and location. No such platform had ever existed, and Lomax believed that by encouraging comparative cultural analysis, average users could gain holistic knowledge of music, dance, and systems of social organization. This virtual Kuntskammer, which would not only contain but also dramatically extract musics from their physical origin sites, recalls those cybernetic fantasies of taking consciousness (information) from the bodies to which they had been linked. Massive recording devices were no longer necessary, as the folk’s voice could now be written onto computer storage material. With audio-visual aids, the layman and scientist together could systematically map the migratory patterns of musical traditions, and the conditions under which musical transformations occurred could possibly be replicated or avoided. As Szwed writes, “Everyone could find his own place in the cultural world, locate his roots, and trace his links to peoples and cultures never imagined.”

Though the Global Jukebox attracted the attention of multiple organizations, including Apple, no one invested. Like Lomax himself, the idea dawdled between the equally profound abysses of pop culture and academia. The Association for Cultural Equity, currently run by Lomax’s daughter, Anna Lomax Wood, recently launched the first part of the reconceived Jukebox. This Global Jukebox Song Tree contains nearly 6,000 songs. The website is still an open beta — if you search the navigation bar, you will find many categories like “Patterns” and “Similarities” greyed out — and the interactive globe looks something like a demented color wheel. However, this is not Pandora Internet Radio. Pandora, the consumer-oriented cornerstone of the Music Genome Project, uses 400 musical attributes to predict which kinds of songs (most of them produced by popular artists) a user is most likely to enjoy. A limited feedback system — one has ability to vote thumbs up or down on a song — accentuates one’s lack of agency in tailoring her musical stations. If the Jukebox echoes the flexibility of a direct democracy, Pandora operates as a kind of totalitarian democracy which dictates, through matching algorithms, the listening experience of the user. Well before the capitalistic din of online music services like Pandora and Spotify, Lomax observed, “Standardized programs of merchandising…and mass media [had] taken over or encroached upon the terrain of local creators and customs.” About this he has never been wrong. The Song Tree seems a prognostic of a moderate renaissance, which will likely be limited to schools, conferences, and academic papers. Traditional folk has never been more visible than it is today, and yet few know the extent of its influence, or where to find it.

Look to the South. Look towards the western shore. In Mexico, Curaçao, and Italy. In-between any two wars. It will be there.

***

“There’s been no time or energy left over, but someday I think you’ll all be pleased with how things have turned out.” — Alan Lomax

For Promise Land, history begins in the first census to be released after the Civil War and the abolishment of slavery. The Census of 1870 is the first to list former slaves as individuals, and in it a 35-year old woman named Lucinda Hall, mother of nine, is described as a Head of Household. Rufus and Jerry Robertson were two of her children. The lineal tree I constructed is crude and more faithful to a descending stream of pitchforks than something as sprawling as an oak or pine. Still, a bloodline in black ink is lovely. I received from my grandmother in the mail a package thick with photocopied images of the Bowens, Nesbitts, Edmondsons, Langfords, and Robertsons. There is one picture of schoolchildren organized in rows. Most look like they have been chastised, for only one aberrant boy smiles. Those standing in the back are the older children, and most of their faces are illegible in the sunlight. Someone has drawn lines from each person’s face to the edges of the paper where their names hang like keys on thread. When I waded through the miniature histories compiled by my family, I found that some names were recycled. Rufus, son of Rufus and Hersey, son of Hersey. A host of Marys.

Had Lomax driven through, he would likely have recognized Promise Land by virtue of its anonymity, a dot on the broad map of his intuition. Theo and the Promise Land Singers are crooning like canaries now from within the church-house. Nothing like “The Balm in Gilead,” but something Protestant and rigorous like “This is the Day the Lord Hath Made.” Lomax will be there on another Sabbath day and park in the field of tall grasses opposite the church. The doors are open and the deacon begins to think of a fitting prayer that will not only shelter the parishioners as they return to their homes, but inspire fear of wrongdoing and love of virtue and fellowship. Lomax cannot see the deacon clasp his sweaty hands together, but he is busy listening. Today He rose and left the dead/And Satan’s empire fell/Today the saints His triumphs spread…The song rolls out and stumbles down the stairs. He doesn’t need to go inside. He’s heard the hymn before, dozens of variations in Georgia or Mississippi, each performed with greater tact. He inspects himself in the side-mirror and realizes that he’s forgotten a tie, his buttons are misaligned, and he looks tired as hell. He lets the engine stutter and slips his arm out the window. He taps the car door in tandem with the deacon’s prayer. He has no notebook, only busted shoes, and he must be on the road to Washington again. “Amen,” the deacon says, and the congregation echoes, “Amen.” Lomax opens his door and Promise Land comes out. All the saints laugh as though joy is only given unto them.

∞