In the [Size 12, Men’s] Footprints of My Forefathers

This essay, by Nassau Literary Review Staff Writer Ayelet Wenger, was originally published by The Times of Israel.

“Whoever is not wearing Tefillin can just walk out,” the Rabbi announces from the other side of the high school Mechitzah. I am not wearing Tefillin. I know vaguely that there are women in schools that are not my school who wear Tefillin as if they are Jews. I do not think the Rabbi is talking to them. Nor to me. I want him to be talking to me. I want to believe that, as a person in a synagogue not wearing Tefillin, I can exist.

I walk out.

Nobody notices.

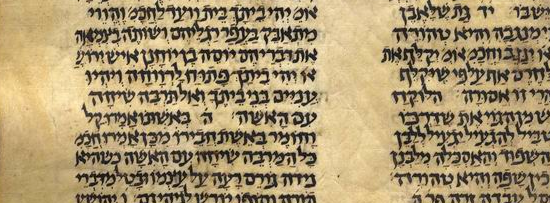

I pray in man. In false pronouns. In the linguistic space of a foreign gender. In a collective maleness that is grammatically explainable because, well, that’s how Hebrew works. Every week in Yekum Purkan I beseech God on behalf of “this entire holy congregation, them and their wives.” I do not want this wife of mine, and even if I did my holy congregation would forbid her, but still I pray for her. The possibility that I am not a member of this holy congregation, that I am just a wife of, must not be.

I am your manservant, son of your maidservant.

Seven women squeeze together into a tiny college dorm room on the eve of Purim. We have run out of festival songs and now we are singing the slow songs, songs that hum back to the canned peaches of synagogue Seudah Shlishit, to moments in summer camp when clamped eyes first tried to squeeze a path to Him, to sunsets with sisters that remind me of past sunsets reaching back through the pages of eternal life to a mountain somewhere in a desert when we first heard His voice.

I am your maidservant, daughter of your maidservant, one voice corrects. She is right, of course, we are no manservants, of course, we are no sons. The womanly voices continue with the new words but I cannot follow this better song, this new song. It is not a song of canned peaches or sunsets. Years ago I discovered my God in man and I do not know if I can find Him in another language.

Does God care how often I lie when I speak to Him? Rabbi, does He even notice?

There are the brackets, of course. Please remember to insert your

brackets. Halachik [Wo]Man, Lonely [Wo]Man of Faith, May God bless maleyou [and femaleyou] and safeguard maleyou [and femaleyou] and shine His countenance upon maleyou [and femaleyou] and place upon maleyou peace [and femaleyou (if you’re still there)]. Yedid Nefesh / Father, the merciful / draw your manservant / in the sense of, you know, maidservant. Somehow I rely on these meandering approximations, these words outside of words, to articulate myself within a tradition in which Creation is a matter of words, in which letters are worth crowns. Somehow I pray in sort of’s.

And if they are not prophetesses, they are the sons of prophetesses, wrote a medieval Ashkenazi scholar of the pious women. (Teshuvot Rabbenu Tam 48:7.) Mothers of old, what were you, you prophetesses, you sons.

Do not cut off the corners of your heads and do not destroy the corners of your beard. (Leviticus 19:27.)

“A beard? Only boys have beards. Is God just talking to boys? No, he’s talking to everybody, since He just said Kedoshim Tihiyu and that’s not just for boys, right? We’re all holy, right? And He told Moshe to speak to the whole nation of Israel. That’s girls too. Why doesn’t Rashi say something? God’s not just talking to the boys, right Ima? Right, Ima? Right?”

Is God talking to me? Ima, was He ever talking to me?

Shmuel HaNagid walked inside a Beit Midrash and they were fighting and too much, too loud, too great the strife:

Do you place yourself among the males? / And God will testify for you that you are a female / rebuked Shmuel HaNagid.

You flaunt your phallic soul, / but the Lord will prove you hollow / translated Peter Cole. (Peter Cole, “Shmu’el Hanagid” in The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain (Princeton University Press: January 2009), http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7rvzk.)

How sensitive of him / to wipe me clean / from the page.

Ishah Bei Midrasha Lo Shechicha — A woman in the Hall of Study is not to be found. (bMoed Katan 18a.)

I glance up from my tractate and the Beit Midrash, my Beit Midrash, is swirled with skirts. I smirk at the anonymous Stamma, who smirks back at me. You’re still reading me, aren’t you, he grins. You will never cut out the way I cut you out.

But I was there for the cutting, wasn’t I? Look, I’m here, the woman in the Beit Midrash, page 18a of Mo’ed Katan, not some historical oddity with a spinning wheel but a real live text-fingering woman just like me, look fast and you’ll glimpse me right before he cuts me out. Right before she is not to be found.

It is not that a woman packaged in the phrases of men is so strange. Helen according to Homer, Eve according to Rashi, Lolita according to Humbert Humbert according to Nabokov. Herstory the striptease, glimpses of her nothing but figments of the male literate imagination, the virginal unknowability of our dead matriarchs as rigid as the eternally crinkled folds of a Grecian statue. Peek between the lines of our Authormen and you might see a discarded hair clip, a menstrual cramp, a wish.

Her name was Melania the Younger and she has been preserved for us by Gerontius the Man. His Melania is a paradigm of the pious female. “In case anyone should think to criticize me for praising a woman,” Gerontius writes, “I would say that one should not refer to her as a woman but as a man because she behaved like a man.” (Gerontius, “The Life of Melania the Younger” in Lives of Roman Christian Women, trans. Carolinne White (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 182–183.) Did you cry like a girl when you read yourself unsexed, Melania? Or was there salvation in a gender fluid as a metaphor, in a removable femininity? Did you care to become equal to a man when you could be man Himself?

A poet once wrote of those womanly folk, “Who, vague-eyed and acquiescent, worshiped God as a man. / I’m not concerned with those cabbageheads, not truly feminine / But neutered by labor. I mean real women, like you and like me.” (Carolyn Kizer, Mermaids in the Basement: Poems for Women (Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 1984), 41.)

I dwell among the poetic cabbageheads. We have lost our femininity, Melania and I, we cabbageheads, we unreal women. Except when it knocks me on my Tefillin knot. Except when the tip of my chest accidentally brushes a low-hanging Tosfot as if my body were a body, as if this book were not designed for this body. Except when I walk into synagogue to see nine disappointed faces pointed past me, waiting for someone who counts.

Waiting for the coming of someone man enough to look Him in His Tefillin knot and cry:

Your texts trapped me in the voice of a man.

And our Father shall reach with outstretched arm and with a flare of anthropomorphic nostrils. Manly tears will stream down the Divine face that Maimonides never did manage to erase from the Bible and my God will speak from the depths of the metaphor to mankind in which He dwells, saying:

Me too.