What We Loved in 2015

With its biting lyricism, bare bones strum-style, and immense ability to make the mundane interesting, Courtney Barnett’s Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometimes I Just Sit was one of the finest albums of 2015. Barnett dabbles in classic singer-songwriting techniques, but her ability to avoid the pitfalls of the genre on her debut record — seriously, there has not been a better first LP since FKA twig’s LP1 — is what sets her apart from the glut of simpler-is-better guitarists. After all, only someone as talented as this young Aussie could make a song about pesticides and corporations not a preachy mess — “Dead Fox,” check it out. She doesn’t stop there either: Sometimes I Sit is a full three-quarter hours of social commentary better than what most musicians accomplish in their entire careers. While not quite as facetious as Father John Misty or Modest Mouse, Barnett still manages to inject humor into her insights, making the album far more listenable than something like Sun Kil Moon’s Benji. (Though that’s a great album in its own right.) It’s this balance between humor and humanity that makes Barnett’s work so seminal. And, at only twenty-eight years old, Barnett should be our favorite sardonic troubadour for quite a while.

— Paul Schorin

James Wood got it right when he was reviewing Marilynne Robinson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Gilead: “To bloom only every twenty years would make, you would think, for anxious or vainglorious flowerings. But Marilynne Robinson…seems to have the kind of sensibility that is sanguine about intermittence.” Though she’s published only four books, three of which are related and the first two twenty years apart, Robinson’s narratives seem neither languid and overdue nor clumsy and harried. She is indeed like an orchid: her appearances may seem capricious, but she never (re)blooms without good reason, and everyone pays attention when she does. It’s why Robinson’s latest book, Lila, was a wonderful surprise when it was released just in time for last Christmas.

I picked it up with excitement — it had been six years since her last novel following the lives of an aging preacher, his simple younger wife, and their unexpected son. The books can be read in any order; the plot ambles through midcentury Iowa like its cautious and eponymous protagonist. It’s easy to walk alongside her toward nothing in particular but away from everything specific. Those of us who read and loved the previous two installments, Gilead and Home, know well what life awaits her, and those venturing into the town of Gilead for the first time certainly engage in the quiet but gripping journey. It is powerful without being florid, intelligent without being pretentious, and religious without being domineering. In a year that brought a lot of change to my life, Lila left enough room for me to think and reflect while still fully inhabiting its own fictional space. If you need your next meaningful read, run to the nearest bookstore — or, just get there on your own time. Either way, Lila and Marilynne will be waiting.

— Owen Ayers

I’m only a few letters deep into the hefty Letters to Véra, but I’ve noticed already that it’s pretty wonderful. This book is a compilation of the letters Vladimir Nabokov wrote to his wife and soulmate throughout his life, shot through with poems. The pages I’ve read so far amount to something akin to autobiography but far more intimate. What a delight it is to read along as Nabokov crafts a just-so Nabokovian metaphor. What a delight to see more of the marvelous mind at work, to be allowed to peer into where the beautiful ticking noises came from.

Nabokov kept a tight control over his words, as you can tell from his books. He almost never submitted to in-person unprepared interviews. And so it was a novelty to me to have been able to read in 2015 a seemingly more unfiltered Nabokov in these personal letters. See the many false starts and the proliferation of punctuation in his first letter’s first line: “I won’t hide it: I’m so unused to being — well, understood, perhaps, — so unused to it, that in the very first minutes of our meeting I thought: this is a joke, a masquerade trick … But then … And there are things that are hard to talk about — you’ll rub off their marvelous pollen at the touch of a word … They write me from home about mysterious flowers. You are lovely …”. The earnestness, headiness, realness here — very different from the immaculate, highly polished prose of his novels. And in the copies of the original letters provided, I’d swear there’s something in the way the lines of writing list to the right, as though Nabokov looked at the page and the world from some slightly slanted/greatly rarified angle…or that’s the kind of thing you might imagine as you read.

Of course you can open up to any page for some perfect Nabokovesque morsels of description and wordplay. There’s too much of this good stuff to choose one bit to quote here. And of course the marvelous menagerie of pet names Véra accumulates — goosikins, sparrowling, my little music, my dear life, long bird of paradise with the precious tail, a few of hundreds — must be mentioned. If nothing else, you can learn from Letters to Véra how to write well to your sweet darling. But for me the revelation of the book is the work it does to humanize and personalize one of my favorite writers. Even if you don’t care at all about any of that, Letters makes for very fine reading. I’d recommend it to anyone.

— Terry Oshea

I was supposed to have known about the South-African animator and printmaker William Kentridge before going to see his production Refuse the Hour at the BAM Harvey Theater. In the performance, Kentridge is concerned with time. What can we do with it? How can we deform and transmogrify time, or even stand outside of it? How have colonizers deployed time to their advantage? How do we represent this onstage? The production was rich and multivalent. There were no conventional characters, no plot of which to speak. Kentridge himself was orchestrator and performer. I didn’t expect him to be as exciting as he proved to be. He framed individual sections of the show with fascinating mini-lectures that encompassed everything from Homer to entropy to black holes. The lectures were organically subsumed by the players around him, including the charming dancer Dada Masilo and a vocalist named Joanna Dudley.

Dudley’s performance — perhaps the most enthralling I’ve seen all year, in any medium — is difficult to describe. The Italian futurist Luigi Russolo created a set of instruments called the intonarumori (noise makers). They were large boxes with horns protruding from one side. Inside them, a wheel touched a string attached to a drum, which functioned as an acoustic resonator. Listen to a recording of these instruments and then imagine those noises coming from a woman’s mouth. Dudley was the unorthodox heart of an unorthodox show. I will always remember the duet between Dudley and the powerful operatic singer Ann Masina. Masina would sing something beautiful and traditional — I can’t recall in what language — and, like an otherworldly positive feedback loop, Dudley would sing something back into the mouth of a giant horn. The sounds she emitted were impossible, like whispers of an android’s specter. It was a play of hectic dance, quivering arias, vocal distorters, background animations, and drums hanging from the ceiling. Odd and exquisite.

— Aaron Robertson

Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac is bleak, unflinching, sexually explicit, and four-plus hours long: in short, not a film I expected to watch — much less enjoy — on Christmas. But a friend cajoled me into giving it a try since we were both on campus and both had nothing to do, and I agreed. I’m glad I did. Nymphomaniac combines the dry humor of LVT’s The Idiots with the wrenching moral twists and turns of his more recent Antichrist, all the while providing an incredibly perceptive (if warped) take on sex, guilt, and addiction. The film was released in 2013 amidst a media firestorm concerning its unsimulated sex scenes; here’s LVT being provocative for provocation’s sake, and more than a few critics grumbled. But I think would be a mistake to write off the film for that reason, as I’d once done. Yes, Nymphomaniac contains a number of graphic sex scenes, but they are interwoven gracefully — never gratuitously or self-indulgently — into its storyline. And like almost all stories about sex, Nymphomaniac is not ultimately about sex. Through sex it explores issues of compulsion, morality, family, obligation, and love as complexly and as satisfyingly as any novel.

— Whitney Sha

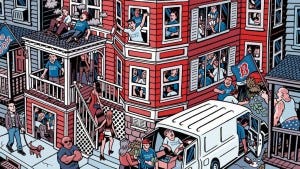

Given that Grantland, one of the finest places for journalism and criticism on the internet, was shuttered by parent company ESPN this October, it seems only fitting to include one of its best pieces on this list. Amos Barshad’s “’Yankees Suck! Yankees Suck!’” is a perfect encapsulation of everything that made Grantland so great. It’s a masterfully told behemoth: seven-thousand-odd words worth of gripping illustration, impossible to put down once started. It’s rigorously reported: dozens upon dozens of disparate interviews amalgamated into a cohesive and compelling tale. Most importantly, though, it’s a masterwork of storytelling. It reveals the passions of the people behind Boston’s punk scene and their complex relationship with the “jocks” of the city. It paints a vivid picture of Boston and the residents who make it such a special city to so many. And, arguably the piece’s greatest strength, it makes the reader care — about the Red Sox, punks, gentrification, hedonism, and the importance of the antagonistic relationship which defined (and continues to define) so much of what makes Boston’s daily life tick. Obviously, as a lifetime Boston-area resident and Red Sox fan, it’s an easy sell for me — but even so, I find its nuanced and passionate portrayal of the city I love truly incredible. Grantland, we’ll miss you.

— Will Rivitz

“Genius!” my Dad shouts. He has just turned away from the TV, and is now shaking his head at me in disbelief. For as long as I can remember, I have sat on this beat-up couch watching comedy with my family. Sometimes, it’s Anchorman. Every Saturday night it’s SNL. Bridesmaids, Tommy Boy, Comedy Bang! Bang!, Portlandia, Harland Williams…my parents had the good taste to let us watch them all. Yet, the program that never fails to blow us away is Louie C.K.’s Louie.

In many ways, the series is a classic. The show features C.K. as a comedian living in New York City. Like in Seinfeld, the episodes revolve around the absurd interactions of day-to-day life. However, the genius of the show lies in the astounding diversity of comedy, and especially the lack of comedy, explored throughout its four seasons. From dates gone wrong and chatting about masturbation to a homeless man’s decapitation and childhood drug addiction, Louie pulls our emotions to the extremes. Laced through it all is C.K.’s standup, always a beautifully dirty pleasure.

But perhaps what makes Louie so special is that, though we expect a show from C.K. to be self-deprecating, the message that ultimately prevails is one of empowerment. Take a moment from Season Three, when Louie is panicking because his date is sitting on the edge of a rooftop. She responds,

“But the only way I’d fall is if I jumped. That’s why you’re afraid to come over here. Because a tiny part of you wants to jump because it would be so easy. But I don’t want to jump. So I’m not afraid. I would never do that. I’m having too good of a time.”

There is something so unconventionally optimistic in these moments that shines through the façade of hopelessness. It reassured me, especially throughout my first semester here at Princeton, that I alone have control over my life and the power to choose what makes me happy.

— Remi Shaull-Thompson

There was a time last fall when I was sitting in a philosophy professor’s office talking with him about the relationship between philosophy and the arts. To me, this professor, who had gained notoriety among my class for telling us matter-of-factly that ever since he read Plato’s Republic and its scathing critique of art he had not read fiction for pleasure, had become a kind of voice of conscience in my head. That voice placed before me a pressing question: why choose literature when philosophy seems the best pursuit of the true, the good, and the beautiful? He was amused by this not wholly accurate characterization of himself — nevertheless he appreciated its pedagogical value — and suggested an answer to my question: look into literary studies.

For anyone who has ever felt a similar ambivalence about reading or simply wondered why it is that we should close-read a text as a thing in itself, as an English professor must have dictated to you at some point, the book you’re looking for is Terry Eagleton’s renowned Literary Theory: An Introduction. Even for those with ample experience, the way that Eagleton retells the story of theory from its beginnings in Romanticist England to its wide-reaching ambition and fame in the era of so-called High Theory of the 1970s and 1980s, giving cogent analyses of all the major movements and elucidating unexpected connections among them with marvelous style and wit, makes for an unparalleled read. Literary Theory is not such much a history of theory, even less so a textbook exposition, but an examination of the very real motivations and implications of different ways of looking at a text, and an adventure through which one comes a good deal closer to learning what literature is and why it matters.

— Alex Lin

I saw The Martian at the dollar theatre on the first Monday of winter break. It was my father’s idea that the entire family go. We all sat in silence, in the cushy red seats in a dark, carpeted room, munching away. With a few other dozen viewers, we watched the screen light up with that spectacular red planet and settled in. Based on the novel by Andy Weir, Ridley Scott’s film follows astronaut-botanist Mark Watney (Matt Damon), who is accidentally left behind on Mars when the rest of the crew is forced to abort their mission in order to avoid being stranded by a deadly sandstorm. This fun space adventure quickly turns into an existentialist’s worst nightmare. Watney is left alone on Mars, cut off from contact with Earth and the rest of his crew. Yet we soon learn that Watney is a smart guy. He’s clever. He’s resourceful. He learns how to grow potatoes in space (it’s more complicated than I’m making it seem but that’s the gist of it).

The anxiety of being alone mixed with the agony of waiting should have made this film unbearable. How can you possibly make waiting interesting? Instead, this film is a gift. A delightful, hilarious, and charming gift that keeps giving, that keeps the audience engaged and alert and always wanting more. The Martian is about survival and about being alone: man versus nature, man versus himself. You will be afraid for Watney even when there’s no time for him to feel fear himself. In an age where smart sci-fi rules — just look to Ex Machina and Interstellar as examples — The Martian literally says ‘fuck you’ to their heavy rules and tropes and creates a smart, daring film. When the crew finally reestablishes contact with Watney, his colleague, Astronaut Martinez writes to him: “Sorry we left you on Mars, but we just don’t like you.” It’s these zippy one-liners, loaded with unspoken significance that cuts viewers in the heart.

I was not alone in that theatre, but there were moments when I felt like I must have been. What a private experience to have — to contemplate such personal thoughts and reflect on my own solitude in life — in the presence of the most important people in my life. The beauty of cinema is the shared experience that film rewards its audience in gratitude for our suspended disbelief, and The Martian shows us its appreciation.

— Angélica María Vielma

While I didn’t necessarily enjoy it, the finale of How I Met Your Mother helped me realize an important lesson. Spoilers ahead. I binged the last bunch of episodes in a flurry, only curious as to how the show would treat the most dramatic/meaningful moments of Ted and Tracy finally meeting, having a first kiss, etc. Why? Because, as annoying as he is, Ted is one of the few characters we have in modern TV who is a true hopeless romantic. I identify with his whining about finding “the one.” (I mean, it’s probably more than 1, but even if it’s 1000, the odds of each person you meet being one of them is 1/700,000, i.e. it’ll be a struggle to find and identify one!) Maybe there are better TV romantics, but this one seems to be the most widely watched, most popular show, which focused on a specific romantic quest.

The finale was so interesting to me because the audience demanded a certain ending. And ending that annoyed me because it was stupid, but it also deeply resonated with me. How I Met Your Mother is a bad show. (In fact, it has always been just a social activity for me; I’ve never watched it by myself.) The ending took many things Ted said about the mother in earlier seasons and threw them out the window. The way he talked about the mother before the finale indicated that she surpassed all other women for him, and she’d be the last woman he’d ever date. It goes against the show’s mantras for Ted to get over her after six years. But the audience wanted him to end up with Robin. In a way, it was crazy of the audience to want Ted to be with Robin, a woman he’d unsuccessfully dated previously, his friend’s ex-wife, and someone who’d explicitly told him she did not love him. They preferred her to Stacy, the perfect woman for Ted. I realized that the sizable audience of the show preferred a complicated, messy love story with ups and downs, a story about love that flourished in spite of differences in personality, a story between two people with wildly different ideas about love. Ideas about romance are clearly changing, but the idea about unique connection, which can appear immediately or over time, whose pull can feel alternately like a magnet or like destiny, and with such an intimate and yet exhilarating feeling, remains.

— Justin Poser

To read Jeff Nunokawa’s Note Book is to encounter a collection of writing in exile. Drawing from the thousands of digital meditations he has published daily since 2007, Nunokawa — now the “Montaigne of Facebook” — has expatriated 279 of them to print. These brief essays ease the romantic tension between technology and aesthetics: they make the Internet a platform as intimate as not only conversing with a text, but going to bed with it. Here, we share a citizenship with Nunokawa in the wilderness of loss, loneliness, and “agreeable melancholy”. It’s ultimately an Eden for reuniting the critical with the confessional, and the lover’s discourse that ensues resists summary: it takes anything from George Eliot’s Middlemarch to lyrics by The Postal Service as its starting principles, each quotation “a well-meaning networker working […] long past its due date.” At first read I’d say these literary negotiations marry the obsession of Nabokov’s Pale Fire with Frank O’Hara’s perennial sense of emergency, but perhaps negotiation is the wrong word. Note Book is less of an argument than it is an epistle to writing “in wonder” over writing to win. In a briefer note, Nunokawa explains this à la Virginia Woolf — “Why this overmastering need to communicate with others?” His reply lives in the heart of his project: not because he’s good at it, but because “it may be [his] only shot at being good.” Read Note Book for the same reason. Pick at least a page a day, but be sure to see it out until its final gloss — while 2015 might be coming to an end, Nunokawa’s efforts are far from over.

— Nicolette D’Angelo

Over Thanksgiving Break, I binged upon Aziz Ansari’s new addition to Netflix, Master of None. I loved it. I have many friends who didn’t, who found the first episode boring and “poorly acted.” Master of None — if I were to defend the show in one word — is grounded. The acting is naturalistic, refreshingly devoid of the theatrics of today’s dramas. Ansari et al. interact as if at home — because they are. The restaurants, coffee shops, and bars are favorites of Ansari and his real New York squad. Their performances, if underperformed, are more aptly categorized as conversations amongst friends, which is partially what makes the show so appealing to 20-or-30-somethings. This relaxed tone seems intentional, a nod by co-creators Ansari and Alan Yang to their audience, as if to say “You know we are writing the show that we want to write.” The series revolves around this contract: we watch Ansari’s character Dev rant about anything and everything that angers the two writers, as struggling entertainers and struggling adults living in the wonderful and terrible land of texting and Tinder.

Enter Dev’s quest for modern love and we are given the emotional core needed to root the quick jabs made at other facets of adulthood throughout the series. However, Master of None is anything but a rom-com with the occasional tangent. Rather, the show progresses like life: chaotic, silly, monotonous, scattered. The tangents, like finding the perfect taco, take center stage. Love happens along the way. The inconsistent attention paid to work, to family, and to girlfriend weaves together to carve out the life of a likeable and relatable main character.

What’s more, the binging feels worthwhile because of the show’s overarching socio-political commentary. One of the most poignant episodes comes towards the beginning of the ten, when Dev and his friend Brian decide to thank their parents with an appreciation dinner. Hilarity ensues, sprinkled with grit as it articulates the disparity between immigrant parents and their first-generation children. Another personal favorite is Dev’s anger over racism and ethnocentrism in the casting industry, especially when juxtaposed with the show’s overtly diverse cast, a long and painful slap in the face to whitewashed Hollywood and its perpetrators. Master of None is worth not only a watch but also a conversation.

— Raina Seyd

“Non-Stop” is the Act I finale of Hamilton, but, having not seen the musical live on Broadway or elsewhere, I know the song better as the cast recording’s twenty-third track on Spotify. The part of the song that got me choked up on my way to the library is when Leslie Odom Jr.’s Aaron Burr narrates the origin of The Federalist Papers: “The plan was to write a total of twenty-five essays, the work divided evenly among the three men. In the end, they wrote eighty-five essays, in the span of six months. John Jay got sick after writing five. James Madison wrote twenty-nine. Hamilton wrote the other fifty-one!” Burr is speaking for this — he starts getting louder at “John Jay,” and pauses after “Hamilton wrote” before roaring “the other fifty-one!” I’m trying to figure out why “the other fifty-one” made me cry, and I think it’s because Burr’s roar believes that the act of writing is something tremendous. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s act of writing Hamilton, the album’s 20,520 words, makes me a believer in the same.Hamilton affirms that this world full of argument, commentary, and noise needs still more words and more writers. But which words, and which writers?

In “Non-Stop,” Burr starts to sing again, asking Hamilton, “How do you write like you’re running out of time?” The answer is that Hamilton really is running out of time, but also that he knows no other way to write. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Alexander Hamilton, rapping on repeat his mantra, “I am not throwing away my shot,” ends the song sounding desperate and breathless. Writing worth roaring about is desperate in the sense that it is necessary and breathless because it needs to be heard everywhere. Here, at the end of 2015, I’m thinking of this year’s desperate and breathless writers who wrote because they knew no other way, who have written more than they ever thought they would or would need to, whose work will make posterity cry for the sheer effort of it all. But Hamilton and Lin-Manuel Miranda are not just writing for and about history. Their actions are tremendous in their moment and for their moment — right now. A resolution for 2016: read like you’re running out of time.

— Will Lathrop