What We’re Loving — Spring Break 2016

Side Pony, released in February, is the fifth studio album by Lake Street Dive. Based in Brooklyn, the band stars Racheal Price (vocals), Bridget Kearney (upright bass), Mike Olson (guitar, trumpet), and Mike Calabrese (drums), who met while attending Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music.

Side Pony is such an impressive album due not only to the sheer talent of the band, but the modern sound and energy it brings to classic styles. The album flirts with many genres, from soul and R&B, to rock, indie, and even a touch of folk. Despite the album’s resistance of categorization, it maintains a style that is uniquely Lake Street Dive. Price’s soulful, monumental vocals are supported by both male and female backup singers. Kearney is not only a female bassist, but rocks an upright. And, all four members contributed their own songs to the album. The result is a collection of songs that cover an extraordinary range of emotions.

Listen to the opening track Godawful Things and you’ll hear a twist ending worthy of Abbey Road. From the melancholy of Mistakes, to the passion of Call off Your Dogs, and the carefree Can’t Stop, Side Pony is a celebration of music and life. I’ll echo track nine, and shout, Hell Yeah!

-Remi Shaull-Thompson

This first thing I said to my friend upon viewing Anish Kapoor’s Adam was, “I hate this. Holy shit, I really, really hate this.”

It was spring break and we were wandering through one of the galleries at the Tate Britain. In front of me stood a large, four-sided, reddish piece of sandstone, towering a foot or two over me in height. From far away, I could see that a single, large black rectangle had been painted on one of the sides of the sandstone.

Initially, I dismissed the sculpture as another archetype of modern art I would never understand (a black rectangle on a rock in a museum!). But upon further inspection, I found that I could not tell if the rectangular shape was painted black or carved into the stone itself. I leaned as close as I could to the sculpture, and stared into the rectangle. Have you ever been surrounded in the kind of darkness where you open your eyes as wide as you can and you still can’t see anything? This is what it felt like. The infinite quality of darkness was terrifying. If I blinked hard enough, I could see hints of dark blue, barely contrasted against the blackness. The rectangle was so dark that I couldn’t actively convince myself that it had been painted on the surface of the stone, or that it was a rectangular-shaped cavity. I wanted so badly to touch it, to reach in and see if my hand would brush against sandstone or an empty cavity. At the same time, I liked the Schrödinger’s cat quality of it being both. (The description indicated it was a cavity, by the way.)

I don’t know much about modern art; I also don’t consider myself an art enthusiast. But once in a while I see something and I feel things that I cannot explain. Looking at Adam ignited a passionate hatred in me. Why it was hatred and not anger or confusion still puzzles me. But regardless, the piece sparked something in me; I talked about this sculpture for days after seeing it. Kapoor’s Adam reminds me why we still make art.

-Megan Tung

Despite never having read any of his work, I attended a reading and a discussion with Ben Lerner while he was teaching at Princeton last year. I was interested in the hype surrounding his sudden literary superstardom but I wasn’t a poetry person (my excuse for having avoided his poetry) and the premises for his two novels both sounded rather pretentious (my excuse for having avoided his fiction). I found him surprisingly down-to-earth in discussion, so I picked up his novel Leaving the Atocha Station this spring, bracing myself for a helping of the ironic postmodern disaffectedness that’s all the rage these days but willing to give it a try. It gripped me from the first page. A middle school English teacher of mine once remarked that poets have a different relationship to language than prose writers do, and for Lerner, who is primarily a poet (or first gained fame for his poetry), I definitely think that’s true. His turns of phrase are unusual, elegant, and — each one of them, once you pause and consider them — astonishingly apt; every word holds weight. The first-person narration of his protagonist, too, is disarmingly sincere; Lerner’s relentless probing of his protagonist’s shame, insecurity, and ironic disaffectedness reveals profound psychological insight. I regret not attending more of Lerner’s events last year and most of all not enrolling in one of his poetry courses, but I’m infinitely glad that I started reading his work at all. It’s one of those rare cases in my opinion, but his explosive fame is well deserved.

-Whitney Sha

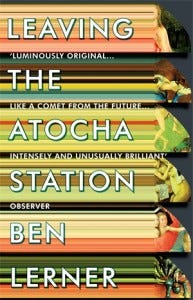

While the increasingly popular “black dandy” aesthetic seems to suggest that urban fashion is incompatible with high art, “Passing/Posing” — the first museum show by Brooklyn-based artist Kehinde Wiley — certainly begs to differ. Composed of 18 large-scale oil portraits, “Passing/Posing” depicts its black subjects wearing street clothes while engaged in private moments of introspection, prayer, and intrigue. In these moments, gold chains become crests of black excellence and prestige; oversized jeans give Wiley’s subjects the permission to take up space in the world of culture and aesthetics. And these subjects have artistic similarities beyond the sartorial: from the surprisingly masculine “Female Prophet Anne” to the surreal, ceiling-sprawling “Go,” each portrait features an ornate background threaded with Islamic latticework and Rococo detail. Ultimately, by juxtaposing his subjects’ urban uniforms with such regal backdrops, Wiley draws a parallel between the grandiose past of 18th century Europe and modern-day street fashion in the United States. He presents these two cultural phenomena as equal: united in composition, they are equally deserving of representation, of study, of celebration.

Especially in post-Ferguson America, this equality is crucial for correcting our society’s denial of visible blackness. In an interview with Vibe magazine, Wiley disclosed that “Passing/Posing” is largely a response to “the absence of young black, urban men in painting,” especially in Renaissance-style contemporary works. “This is my way of saying yes to us,” he says. And in saying yes without compromising urban fashion, Wiley integrates his subjects into a world of cultural fluency and social mobility often off-limits to minorities in art, allowing them to finally pass and pose as themselves.

-Nicolette D’Angelo

A movie about more than sloths running the DMV — although that was highly enjoyable — Zootopia is an animated detective flick worth talking about.

In a world where humans have mysteriously disappeared and Disney-style talking animals have overcome the whole prey-predator dynamic that would be a setback to peaceful living, Zootopia follows young Judy Hops, a naive but determined daughter of carrot farmers with big dreams of being the first bunny cop in history. Upon arriving to the NYC-equivalent, Zootopia, Officer Hops finds its motto, “Anyone can be anything,” is anything but true. Judy is instantly isolated from her fellow cops, all imposing predator-types (save Chief Bogo the cape buffalo, of course). After pissing off Bogo big time with her go-getter attitude, Hops soon finds herself in trouble: she must solve the case of the missing otter, Mr. Otterton, or it’s back to the carrot farm for her. For help, Judy outsources to her new acquaintance, Nick Wilde the hustling fox, who acts as the street-savvy “Listen to me, kid,” voice throughout the film.

But the movie is so much more. At one point, a friendly donut-loving cheetah calls Hops “cute.” She responds with something along the lines of, “It’s okay for one bunny to call another bunny cute, but when other animals do it, it’s just kind of…,” the preferred treatment of the N-word in America.

As the movie progresses, Hops and Wilde uncover an enormous conspiracy: mammals are inexplicably turning savage, and the only mammals affected seem to be predators. Soon, as a result, predators are being treated differently — because savagery is “in their biology,” an innate predisposition to violence the world must protect itself against. Cue the not-so-subtle race allusions.

What we learn is that Zootopia is a city run on prejudice. Nick Wilde confides in Hops that since the world expected him to be the sly fox — to lie and cheat and steal — why would he try to be anything else? When the predators-turning-savage news is made public, Hops tells Wilde “we’re not like them.” Wilde, a predator himself, responds, “Oh, there’s a them now?” The most striking tableau — and the most explicit “we are dealing with race now” freeze frame — comes when Wilde asks Hops about the fox-repellant she carries in her belt (the spot normally designated for a gun). Is it because she thinks he will attack her, because he is a no-good fox, because he is a predator?, he growls, bringing his claws closer and closer to her face. Hops, startled, reaches for her repellant. They both freeze for a second, recognizing the moment’s weight. This is her friend. And yet, there Hops stands, in a police uniform, about to pull her weapon on a member of the “them” class.

-Raina Seyd

“Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears.” So said the infamous Marc Antony in William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. I ask you, readers of Nass Lit, to lend me your eyes as I write to you from Julius Caesar’s home: Rome, Italy. As a prospective Classics concentrator, this is the hotspot of Classical learning. Seeing the physical ruins of the ancients we read about really brings the Romans back to life. The Romans were amazing engineers and created miraculous works of art and a (somewhat) sustainable society. However, particular sites and sculptures also reminded me that we praise a culture that had many dark aspects.

Enslavement was a major aspect of those ancient times and the Romans enslaved whomever they deemed to be inferior (similarly to the Caucasians of the later centuries, however the Romans didn’t ‘discriminate’ by color). Additionally, the Romans enjoyed in amphitheaters that carnage of killing. The Coliseum’s sands not only soaked up the blood of fierce gladiators and wild beasts, but also the blood of criminals who were sometimes made to “perform” their execution (e.g. the criminal may play the role of Hercules and die in the way Hercules died). Death was a form of entertainment for the Romans. I forgot that cruelty as I am amazed by the art and literature. Then, I remember that they were people who had feelings and ones to love. Even the famous figures of history had humanistic characteristics. I wonder how Julius Caesar felt as he was stabbed without hesitation by the Senators, especially one he trusted, Brutus. He may have thought, “Does everyone really hate me this much?”

Will these barbaric customs of the Romans deter me from becoming a Classics major? I do not believe so. I will not ignore that horror that occurred in the past, but I will not let the emotions take over my reason, which is that the Romans still hold some greatness and that we have learned from them with regards to culture, literature, architecture, law and much more. And, I believe, we have learned from Rome’s darkness and our own darkness. Understanding history makes us appreciate how far we, as humans, have come and perhaps to help us move forward and prevent repetition.

-Tashi Treadway

Some context: GilvaSunner is a YouTuber who has uploaded thousands of high-fidelity video game songs to YouTube over the past six years. The tracks he’s uploaded regularly break 100,000 views and sometimes eclipse a million, and he has over 150,000 subscribers. This is not the GilvaSunner that we’ll be talking about here. The other GiIvaSunner — a YouTube account that looks for all intents and purposes identical to the other one, differentiable by a capital I instead of a lowercase L in the username — was created a little over a month ago. Not much is known about the new account: it’s believed that it’s run by several famous YouTube mashup artists, as its pace of one new video almost every hour would seem unsustainable for a single person to maintain for six weeks, but that’s about all we’ve figured out. What we do know is that each video GiIvaSunner has uploaded is a painful bait-and-switch. Anywhere from the first ten seconds to the first minute of each song they upload is identical to the original video game song, but after that things start to get wild. Many songs are edited so that the original melody is replaced with the Flintstones theme music, including the one linked here, but there’s also a fair bit of seamless looping (so that the listener doesn’t realize they’re listening to the same three seconds over and over again for a good while), some flawless audio editing (a repeated motif in the original song repeated even more to the point of absurdity), and even some high-quality mashups (featuring the likes of N.W.A, Owl City, and Linkin Park). Whatever comes of the channel in the future, it’s provided hours of entertainment for now and is an excellent example of auditory manipulation gone horribly right.

-Will Rivitz

I didn’t think anything could beat The 1975’s self-titled first album: a masterpiece devoid of filler tracks, whose every song was a tightrope-walk between bleakness and hopefulness. And so far, I was right. The band’s new album I like it when you sleep, for you are so beautiful yet so unaware of it (to which I’ll henceforth refer as I like it when you sleep) didn’t beat The 1975. Nor did it even meet its standards. But I still enjoyed I like it when you sleep — to the point where I play its best songs on repeat constantly. And I know I’ll look back and consider it one of my favorite albums of the year, even though it fell short of my expectations.

I like it when you sleep sounds happier than the rest of The 1975’s music. It’s a synth-filled, lyrically poetic stream of songs that at times bursts with exhilaration — before tracks that are mellower, like “A Change of Heart,” pull the album back to a moodiness that fans of the band are used to. I had always pictured driving down lonely night streets in my head whenever I listened to the band’s older stuff. With this album, I picture lonely night streets awash with a bright glow. Fittingly, that’s the aesthetic The 1975 is going for now. The promotional pictures as well as those in the album booklets depict abandoned nocturnal scenes with pink neon signs that spell out the song titles.

The album is on the experimental side, and though I applaud The 1975 for stepping out of their comfort zone, the more experimental songs sound like filler. Namely, the last four tracks on the album fall flat. “This Must Be My Dream” and “Paris” sound like contrite bubblegum pop, and “Nana” and “She Lays Down” are acoustic in a way the band just can’t pull off — these last two songs are far more boring than even their slowest synthy ballads. However, there are many songs on I like it when you sleep that are worth a listen — at the very least, “The Sound” and “The Ballad of Me and My Brain.” Tracks like these can stand against the best of the band’s older songs and lead me to believe that, no matter how discouraging it sounds, The 1975 should stick to what they’re best at — indie-electronic songs crafted with complexity and full of energy and emotion.

-Julia Cury

The best horror film since…I am not quite sure, but perhaps since Rosemary’s Baby. The Witch’s insightful visage upon bleak, rustic atrocity won director Robert Eggers accolades at Sundance, but its dazzling attempt, and oh-so-skillful success, at linking history and horror is what will help this cinematic opus become a favorite for those seeking true art in the horror genre. Despite his young age — The Witch is actually his debut feature — Robert Eggers is already a master at the delicate craft of the lingering moment. Indeed, all the finest horror films have these moments, the fuzzy edges but robust skeletons of iconic scenes that remain, echoing, in your skull. Psycho has its drain; The Shining its “Heeeeere’s Johnny!”; Alien and Halloween share the musical tremors that make your heart stop without the slightest provocation except the unseen guidance of the auteur. I will not ruin The Witch for you, but believe me, Eggers has composed brilliance. A shot here, a howl there. The empty prayers, the silent vigils, the chopping of wood for fires never to burn. The Witch is beyond a horror film, really. It has approached the ideal, the oft-unattainable status of a terror film. A horror film shows you scary things and rapidly conducts oxygen in and out of your lungs, but a terror film achieves something more. A terror film shakes you to the core. A terror film makes you question what you thought you knew about yourself and about film. About the weight of a word and the power of temptation. Ladies and gentlemen: The Witch, America’s latest and, perhaps greatest, terror film.

-Paul Schorin