A History Locked up in Stone?

Courtesy of

How Irish Literature Negotiates the Violent Appropriation of the Ancient

[I] who would contrive

in civilized outrage

yet understand the exact

and tribal, intimate revenge —

Seamus Heaney, “Punishment”

In the summer of 1986, Irish writer Colm Toibin walked the entire length of the sixty-year-old border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. What he found was a man-made demarcation that cut across the natural undulations of the Irish landscape, that disrupted families and sometimes comically carved homes and businesses in two. Yet Toibin’s journalistic recording of his journey, Bad Blood: A Walk Along the Irish Borderbalances the arbitrary nature of the border with the deep meaning it has for those living with and around it.

In 1986, the border was still the primary site of contestation in the ongoing Troubles, a violent civil war. It had been erected in 1922, and divided the free Republic of Ireland from the counties of Northern Ireland, which remained in the United Kingdom. At the time that Toibin walked the border, Catholic nationalists were calling for the border’s dissolution, for the reunification of Ireland, and for complete freedom of Irish people from British control. They were opposed by British loyalists within and outside Northern Ireland. The so-called Troubles, which lasted from the late sixties to 1998, are perhaps the most chilling example of the Irish tendency to euphemism. Paramilitary violence between nationalists and loyalists resulted in the deaths of over 3600 people and the injuries of thousands more over this thirty-year span.

Toibin’s book is profoundly aware of contemporary history as one of the most important weapons in this war. He records how local incidents of violence breed monuments, martyrs, and myths that compel retaliation, yielding an endless cycle of intimate bloodshed. Yet even for Toibin there is a type of history that evades instrumental repurposing. On his visit visit to the Beltany Stone Circle, a Celtic structure dating to 2000 BC, Toibin writes:

I started to think about that moment, that second when the final stone was put in place and the circle formed, what difference it would have made to the people who placed it there: something new, powerful, complete…We walked down the hill, leaving the stones to their magic, away from the reminder that there was once a time in this place when there were no Catholics or Protestants; the dim past standing there on the crown of the hill, for once a history which could do us no harm, could not teach us, inspire us, remind us, beckon us, embitter us: history locked up in stone.

Toibin romanticizes the unbroken form of the prehistoric megaliths as well as their pre-Christian connotations. While contemporary history only incites contemporary bloodshed, ancient history here has the power to enable an imagination, however distant, of an Ireland free from violence.

Courtesy of

Toibin’s claim is, however, in conflict with historical evidence and with much of the contemporary Irish literature I’ve read. Irish history and literature repeatedly demonstrate that even the most ancient Celtic relics (mythological as well as architectural) are not points of escape from sectarian conflict, but structures open to appropriation for contemporary violence. And this is important because it contradicts a conception common to those who visit and preserve ancient relics: that these relics present frozen images from a long-ago solidified past, rather than living sites for the construction of actionable–sometimes dangerous–ideologies.

Part II: Historical Use of Ancient Structures

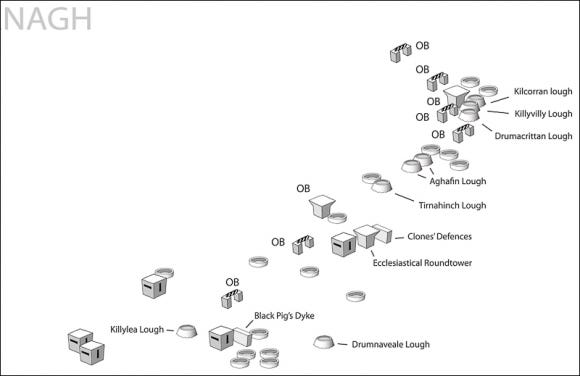

Toibin is obsessed with the image of the border. But the border itself is as much a striking example of the violent appropriation of ancient relics as it is an entirely new addition to an ancient landscape. This is most convincingly demonstrated by cartographer Garrett Carr, who undertook a border pilgrimage that much resembles Toibin’s. Carr’s method is less traditional cartography and more an art form inspired by the physical landscape. Carr calls this “optimistic cartography” because in a war-torn landscape, his maps focus on overlooked aspects of beauty or interest, rather than on the ordinarily mapped geopolitical divisions. Carr’s journey resulted in several such projects, one of which is “The Map of Watchful Architecture,” a cartography of the border that incorporates the assimilation of ancient structures into the border’s route. For example, the Map shows that military towers around the border in southern Armaugh were predicated on the placement of Norman structures in the seventeenth century, which were in turn built around ancient cashels or ringforts. Carr concludes that “All this adds up to what may be one of the longest unbroken traditions of defensive architecture anywhere in Western Europe” and that the Irish border illustrates the way in which “Ancient sites will be reused at different times, by different peoples and for different reasons.”

Garrett Carr,

(2011)

If ancient architectures formed the building blocks of the physical border, they composed an image that justified contemporary violence in complicated ways. “The border,” Carr writes, “was often a Troubled battleground and it was also its metaphor.” Ireland itself had two primary violent divisions, the first being of course her physical partition at the border. The second was the binary division of the Northern Irish populace along strict Catholic-Protestant lines. While Catholics and Protestants were not actually monolithic groups, the ideology of an immutable binary was inescapable. And this binary imaged itself after the division of the landscape at the border. As Carr explains, “Away from the border, in Northern Ireland’s urban spaces, its symbolic value was being re-enacted in the demarcation of neighborhoods [along Catholic-Protestant lines] and by regular acts of violence.”

On a less physical level, the border’s contemporary myths of division are composed of assorted repurposed Celtic myths which inscribe either the immutability of identity or the uncrossability of the borders between realms. In his semi-autobiographical novel Reading in the Dark, about an (unnamed) narrator coming of age during the Troubles, Seamus Deane deftly portrays this conflation of physical and mythical borders. The most poignant example of this appears in a dialogue between two locals living in Deane’s fictionalized border community.

“Dear me, I don’t like what’s going to happen now. Crossing water at dusk is bad luck. It’s tempting fate. The world on the side you leave is never the same as the world you reach. And you know what else about the watery brook?”

“Yes. It marks the border.”

The border is uncrossable for political reasons. Yet its uncrossability has been mythologized, so that it is seen to represent an even more uncrossable entity: the ancient border between the physical world of Ireland and a Celtic spirit world. Indeed, characters in the novel share numerous stories about mythic transformations that have occurred in the border space, as punishment for transgressing the barrier between this world and the next. In these stories, people who dare to cross the border are magically transformed into other people, genders, or animals. Crossing the border violates the Irish doctrine of immutable identity that the border images. It is aptly punished by fundamental identity transformation.

Toibin, who is also obsessed with the manifold meanings of the border, records conversations similar to the ones in Deane’s novel.

“Why do you think we’ll see the end of the world?”

He explained. His mother had heard it from her grandmother it was always said that the world would end…when you couldn’t tell the difference between a man and a woman, when you couldn’t tell the difference between summer and winter.

The use of ancient myths, or at of least mythical phrasing which connotes antiquity, strengthens the perceived necessity of binaries of all kinds. This occurs on a different level from the physical strengthening of the border through ancient architectures, but it is a similar process and a fundamentally connected one.

Part III: Ancient Structures in Fiction and Poetry

Professor Clair Wills, who chairs the Princeton Fund for Irish Studies, once told me Ireland is perhaps the only place in the world where literature and politics are so entangled. This remains my best way to express why I have spent so much time researching Ireland and reading Irish literature. As an English major, I am in love with the way Irish authors use the English language (a language that, it should be noted, is at once a remnant of Ireland’s colonial oppression and Ireland’s main tool for fighting that oppression). I am also deeply interested in the ways that literature comments upon and even influences the historical and political conditions in Ireland. While the Irish appropriation of ancient relics for the facilitation of contemporary violence is, as I have attempted to demonstrate, a historical reality, it was a theme I first noticed in Irish fiction and poetry.

I return then to Deane’s Reading in the Dark, which I have previously described as a coming-of-age story. It is also at once once a characterization of the larger Irish conflict and an intimate portrayal of the conflict’s intersection with the violent secrets of the unnamed narrator’s extended family. These social and political conflicts coalesce in and around the skeletons of ancient structures, and particularly in the physical, political, and quasi-mystical space of the Grianan, “a great stone ring with flights of worn steps on the inside leading to a parapet that overlooked the countryside.” At the base of Grianan, there is a secret passage, “tight and black as you crawled in and then briefly higher at the end.” The stone ring of the Grianan aesthetically resembles the Beltany Stone Circle which Toibin describes as a peaceful monument removed from conflict. Yet Deane’s monument is a weapon, and its internal space is endlessly repurposed as the site of hidden, personal acts of cruelty.

Courtesy of

Grianan is most importantly the site of the elided act of violence at the center of the story, which the narrator eventually uncovers: the political execution of the narrator’s paternal uncle, Eddie, at the behest of the narrator’s maternal grandfather.

So they took him out of the farmhouse and they moved across the countryside to Grianan, reaching it when dark had fallen. They put him in the secret passage inside the walls… Then, maybe, Grandfather took out a revolver and handed it to Larry and told him to do it. And Larry crawled down the passageway… and then he shot him, several times or maybe just once, and the fort boomed as though it were hollow.

Grandfather co-opts the interior of the ancient space as a hiding place for his pivotal act of familial betrayal. In turn, Deane co-opts the image of the Grianan to connect this fictional incident of personal violence to the larger theme of sectarian violence in Northern Ireland. A few miles from the border, Grianan is situated along the demarcation of Irish partition, the primary justification for violent conflict during the Troubles. The politicized location of the execution allows it to serve as a stand-in for the numerous incidents of sectarian violence centered on the Irish border.

Deane plays on not only the physical space of the Grianan, but also its status as a haunted architecture, infused with the violent mythology of its ancient creators. Critic Peter Mahon argues that “Grianan does not just mark a political border: it also marks the border that runs between the natural and supernatural worlds, the fairy and human worlds, and the worlds of the living and the dead.” Mahon asserts that “Grianan thus confers on those who visit it the status of political and metaphysical changelings who may speak with the ghosts locked within it.” Indeed, when he is inside the Grianan secret passage, the narrator imagines the sounds of wind and waves to be the breathing of Fianna. The Fianna are a band of warrior ghosts who were said to accompany the mythical hero Fionn mac Cumbhaill. They are perhaps analogous to the Knights of the Round Table. Their myth can be found in the Fenian Cycle, a body of tales and ballads popularized in Ireland around the year 1000, but it is almost certainly older. As Matthew Schultz points out in his Haunted Historiographies, the myth had taken on contemporary political significance by the time of The Troubles:

In modern Ireland, the most popular mythology surrounding the Fianna is that they lie below Ireland, ready to reawaken and defend the land in the hour of its greatest need — usually perceived as the final battle between Ireland and England. They myth remains particularly attractive to those who see the Northern Troubles as the result of continued British occupation and governance.

It is the new political connotations of the Fianna with which Deane is most concerned. As he feels the presence of these ghosts within the secret passage, the narrator senses that they “were waiting there for the person who would make that one wish that would rouse them from their thousand-year sleep to make final war on the English and drive them from our shores forever.” The Grianan, an ancient military structure, is an appropriate haunting site for the ancient Fianna warriors. And its hauntedness gives the sectarian violence that occurs within it special significance; the Fianna who reside therein are fulfilling their new role by overseeing contemporary political bloodshed. Deane’s use of the Grianan is a poignant fictional imaging of the very real violent repurposing of the Fianna myth.

It makes little sense to talk about Seamus Deane and not the recently deceased Seamus Heaney. The two authors were lifelong friends, and Deane frequently referred to his Nobel prize-winning contemporary as “the famous Seamus.” Both used literature to grapple with the otherwise inexplicable violence in Northern Ireland. Heaney’s writing is arguably even more concerned than Deane’s with the reappropriation of the ancient within the context of this conflict. Indeed, a central conceptualization which crystallizes over the course of Heaney’s career is that of contemporary conflict as primarily a return to the ancient.

In a lecture delivered at the Royal Society of Literature in 1974, Heaney advances this view of the Irish appropriation of the ancient through the image of the bog. In the spirit of Frederick Jackson Turner, Heaney argues that America defines itself by its frontier, and that its historical progression is therefore an outward motion. Ireland, Heaney observes, has no frontiers. Ireland has bogs. There can be no onward and outward in Irish history, only an endless sinking into a bottomless bog, in which the relics of past are preserved. Heaney’s poetry collections Wintering Out and North provide stomach-churning images of these relics. Heaney’s collections are aesthetically influenced by PV Glob’s The Bog People, an archeological study of Iron-Age bodies preserved in the bogs of Northern Europe. In Glob’s photographs of ritually-slaughtered corpses, Heaney finds “images and symbols adequate to our predicament.” The corpses sacrificed to a pre-Christian territorial goddess become an allegory for the many Irish people sacrificed in the religiously-articulated sectarian conflict of the Troubles; they are an image that can “grant the religious intensity of the violence its deplorable authenticity and complexity.” For Heaney, Catholic-Protestant conflict is a re-articulation of “an archaic barbarous rite: it is an archetypal pattern.” It is an atavistic return to the prehistoric tribalism explored in Glob’s study. In this way, Irish history never moves forward, but only digs deeper and deeper into the bog of history, rediscovering the ancient desire to ritually murder one’s own.

Courtesy of Silkeborg Museum

In North, Seamus Heaney deals in relics of the ancient past even as he attempts to make sense of contemporary political violence. Like Deane, Heaney writes about the violent contemporary significance of ancient architectural structures:

I shouldered a kind of manhood,

stepping in to lift the coffins

of dead relations.

They had been laid out

In tainted rooms,

their eyelids glistening,

their dough-white hands

shackled in rosary beads.

In the above excerpt from “Funeral Rites,” Christian imagery situates the grief within contemporary Catholic-Protestant violence. Yet the grief of the speaker is so monumental that he continues:

Now as news comes in

of each neighbourly murder

we pine for ceremony,

customary rhythms…

I would restore

the great chambers of Boyne,

prepare a sepulchre

under the cup-marked stones

One reading of this is that, for Heaney, the ancient megalithic tomb of Boyne represents what the Beltany Stone Circle represented for Toibin: a pre-Christian and thus pre-sectarian space. According to this reading, Heaney wants to bury the dead of both sides alongside one another in Boyne because of the relatively peaceful connotations of this pre-sectarian burial site, resulting in “arbitration/of the feud placated.” Yet the Neolithic period for Heaney is no more peaceful than the contemporary one. Heaney’s desire to bury the Catholic and Protestant dead under “the great chambers of Boyne” is more accurately read as an acknowledgment that ancient and recent historical tragedies are alike and “customary.” The ceremonial response is well-rehearsed because the violence itself is ancient. According to Henry Hart, a scholar and biographer of Heaney, Heaney knows “that the feuds of the Neolithic times, like the stones of passage graves at Newgrange which commemorate them, endure.” We may be tempted to suggest that newer disputes can be resolved by returning to an ancient ceremony, but we are left with the realization that, in order for the violence to have persisted, the ancient ceremony must already have failed. While Carr and Deane depict ancient architectures as neutral but open to violent repurposing, Heaney explores the ways in which ancient monuments may be already intrinsically violent, enshrining the primeval origins of modern sectarian disputes. It is not that conflict uses ancient structures; conflict is an ancient structure.

Courtesy of

Heaney finds that ancient myths, like ancient monuments, are necessary to make sense of Ireland’s atrocities. Heaney does not stop at depicting the appropriation of Irish mythology; his poems also integrate aspects of ancient Greek and Norse mythology, as well as Native American mythic symbols. For Heaney, violence is a human universal that transcends Irish identity and can be found in all ancient tribalisms and their associated myths. In the collection’s titular poem, the author self-consciously describes his ability to transform what he sees through myth, in this case referencing mythical Viking raiders:

I faced the unmagical

invitations of Iceland,

the pathetic colonies

of Greenland, and suddenly

those fabulous raiders,

those lying in Orkney and Dublin…

were ocean-deafened voices

warning me, lifted again

in violence and epiphany.

The juxtaposition of the “unmagical” reality with the violent imagination inspired by emotive Anglo-Saxon mythology demonstrates Heaney’s tendency to mythologize the real, but it also represents an attempt to preserve a distinction between reality and myth. According to Hart, Heaney does not merely use myth to discuss violence in North. Rather, he critiques the appropriation of myth for the purpose of contemporary violence even as he appropriates myths himself. North “doesn’t wallow in cultic mystiques and sloppy surmises,” Hart contends, “but in fact acknowledges the slipperiness and obliqueness of ‘mythical’ language and tries to resist it at every turn.”

Conclusion: A Visit to Lough Derg

I began with Toibin’s description of the Beltany Stone Structure as a respite from contemporary conflict. In the service of circles, would like to conclude by discussing a different monument described in Toibin’s book. Like many Irish writers before him (Heaney among them), Toibin embarked on a pilgrimage at St. Patrick’s Purgatory, on Station Island on Lough Derg. This Middle Age monastery was built on the site where, according to Irish Catholic legend, St. Patrick once entered a cave and was confronted with a vision of the punishments of Hell. Toibin describes St. Patrick’s Purgatory as he finds it in 1986: it is one of the most important monuments to Irish Catholicism, and pilgrimage there not only reveals “a central repository of the faith of our fathers,” but also solidifies the Irish national identity entangled with religious experience. It is this national identity that justifies the sectarian violence taking place only a few miles from Lough Derg, at the Irish border. Indeed, on his own visit to Lough Derg, Heaney penned his long poem Station Island, which tells the story of a narrator who pilgrimages at St. Patrick’s Purgatory and, like the St. Patrick of legend, is struck with a series of visions. These visions are of a Hell more terrestrial than St. Patrick’s; they contain images spanning the history of Irish conflict, implicating the tradition surrounding St. Patrick’s Purgatory in this imbroglio. (Toibin was certainly aware of Heaney’s poem; he references it explicitly in his chapter on Lough Derg.)

The physical site of St. Patrick’s Purgatory is, in fact, the site of a still earlier pagan mystical place. The myth that Saint Patrick experienced visions of Hell in a cave on Station Island may be informed by an earlier Celtic myth that said Station Island was the site of a portal to the fairy world. This monument is a prominent example of the appropriation of pre-Christian structures with the effect of bolstering Christian sectarianism. Toibin writes about how pilgrims to Saint Patrick’s Purgatory are required to cycle, over and over again, through ceremonial Stations: “People moved with a slow, quiet zeal as though they were working in a field, kneeling down and standing up again, moving around a small piece of ground before kneeling once more.” The endless ritual circling finally erodes into meaninglessness. At the Beltany Stone Circle, Toibin interpreted the image of the circle as the image of completion. At St. Patrick’s Purgatory, his description of the endless ritual circling rewrites the image of the circle as the image of endless repetition: a circle may be complete, but it has no end. In turn, while the Beltany Stone Circle is a pre-Christian monument closed off from appropriation, Saint Patrick’s Purgatory becomes a metaphor for the incorporation of pre-Christian sites into an endless, ceremonial, cycle of violence.

Courtesy of