The Bird Who Drew A Little…And Wrote a Lot

By Staff Writer Myrial Holbrook

Any consistent reader of the New Yorker knows quite well that James Thurber, America’s ace creator of sophisticated screwy stories and equally screwy drawings, is mad.

Thurber’s face lit up.

“Oh,” he said, so you know I also write?”

-“Melancholy Doodler,” Los Angeles Times, 1939

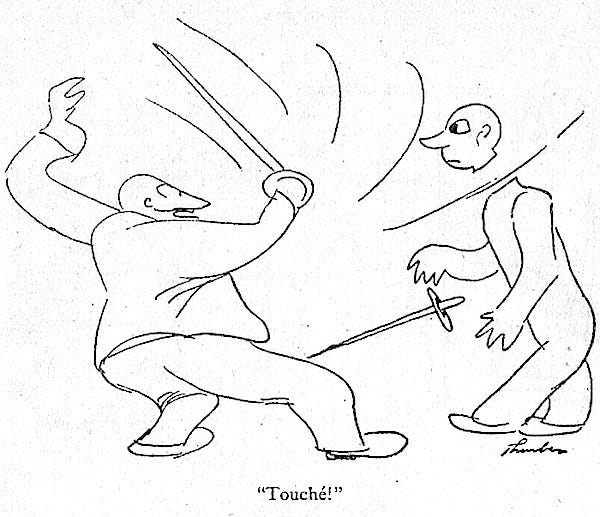

James Thurber never really liked his screwy drawings. They’re odd things — they remind me a little of the blind contours we used to sketch of each other in elementary school art class. Pen firm on the page and eyes locked on your subject, you think you’re in total control. When you finally look at your work, however, it can be surprising or even disconcerting — nose too protrusive, eyes a little beady and misplaced, body curvaceous to an extreme. Similarly, some might call Thurber’s drawings outright crude, and more than a few have called them caveman scratchings. In fact, mothers used to write to the New Yorker protesting as childlike Thurber’s one-panel comics and sending their children’s drawings as corroboration. But his characters — brawny women, submissive men, inquisitive children, and many massive, pensive dogs — have in the ample curvature of their bodies and faces a kind of continuity that is appealing in its simplicity and effortlessness.

His drawings were far from effortless, especially later in his life. As a child of eight or nine playing “William Tell” with his younger brother, Thurber, wondering why his brother was taking so long to shoot, turned around to say something, and the arrow flew into his left eye. For the rest of his life, he sported a glass eye. By 1937, when he was in his early forties, he was going blind. He persevered in his drawing, however, using a magnifying glass and instinct to continue his work. “My imagination isn’t blind,” Thurber often said.

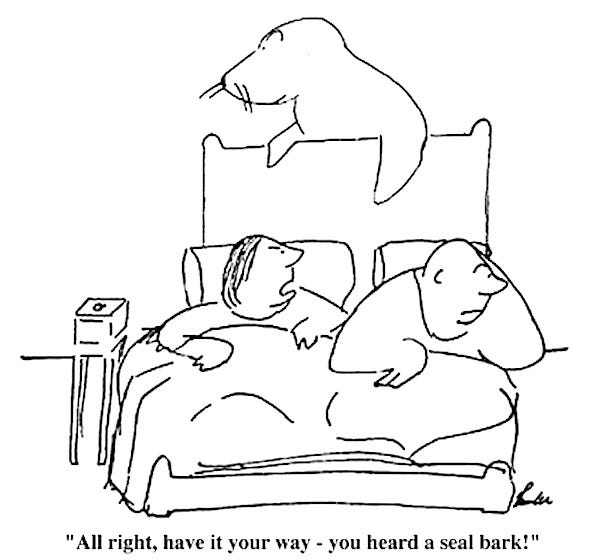

Even when he had full command of his eyesight, it’s a wonder Thurber’s drawings ever got published at all. At first, he scribbled them absentmindedly next to the telephone or in his notebooks; to him they were always just marginal and disposable. In 1929, however, his friend and colleague E.B. White, intrigued by a doodle of a seal on a rock that Thurber had left lying on the floor, salvaged it and took it to Harold Ross, co-founder and editor-in-chief of the New Yorker. After Ross sent it to the art staff for consideration as an illustration, the drawing came back with sarcastic scribbles showing how to properly draw a seal’s whiskers. But White persisted. When White found a publisher eager to buy Is Sex Necessary?, a tantalizing manuscript that White and Thurber had co-authored, White insisted that the publisher use Thurber’s illustrations. The publisher’s reaction was a politer reenactment of the response of the New Yorker art staff, but the book was accepted nonetheless. As it turned out, people loved it all the more for Thurber’s fifty accompanying drawings.

James Thurber wrote thirty-two books in his lifetime (1894–1961): essays, commentaries, short stories, fables, children’s stories, and the occasional play. After he went completely blind, he developed a capacity to compose and edit two thousand words at a time in his head, then dictate the entirety to his wife or secretary. His Broadway revue, A Thurber Carnival, won a Tony in 1960 (though the Tony was purloined and its whereabouts remain unknown). His most famous work is “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” a short story that details an otherwise passive and plain man’s retreat into extravagant daydreams while he runs errands in Waterbury, Connecticut. The story has been adapted twice into film — once in 1947 with Danny Kaye, and more recently in 2013 with Ben Stiller. Strangely, though many people know of the title and the film adaptations, few could tell you who wrote the original story. Thurber’s name has fallen away from much of his work — even the endless comics that turned him into a household name in the 1930s and revolutionized the wit and style of the New Yorker one-panels. In Thurber’s own time, he was often frustrated by the imbalanced perception of his work. As he said in a 1939 interview with Arthur Miller of the Los Angeles Times, “That’s the way life goes. I write stories with the utmost care, re-writing every one of them three to ten times…Yet they say, ‘Thurber? The bird who draws?’”

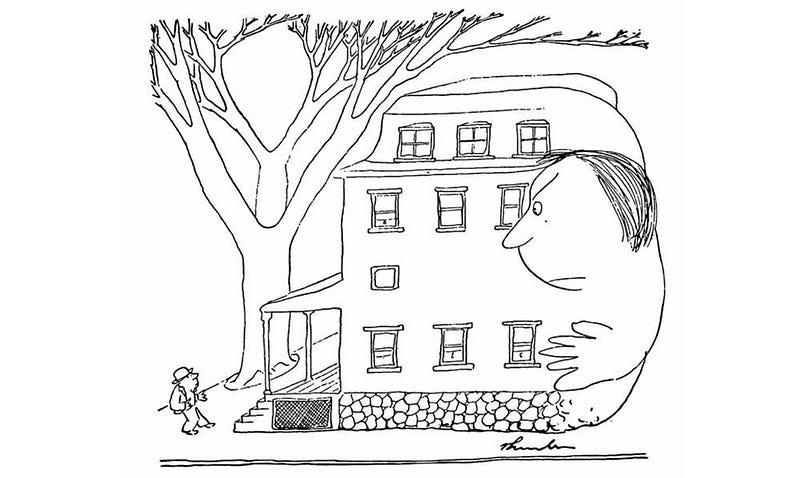

As a native of Columbus, Ohio, and a writer-in-progress, I’ve always been intrigued by Thurber, who grew up in Columbus and attended The Ohio State University. The Thurber House, where Thurber and his family lived while he was in college from 1913 until 1917, is nestled downtown on 77 Jefferson Avenue within a neatly preserved row of Victorian houses. It is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and serves as both a museum dedicated to Thurber and a non-profit literary center. The house is just a few minutes’ drive from my old elementary, middle, and high school. As a constant reminder of this proximity, my school proudly displays in its bricked and shaded courtyard a unicorn statue that is an exact replica of the one at the Thurber House honoring his fable “The Unicorn in the Garden.” Oddly enough, we never in twelve years took a class field trip to the Thurber House. Apparently, trips to the Rumpke Sanitary Dump, positioned so thoughtfully at the southerly entryway to the city, were more important for our education.

I got my Thurber dosage in other ways. In the summer after second grade, my parents enrolled me in a young writers’ workshop in Thurber House. I’m ashamed to say I don’t remember much — certainly not much about the writing, anyway. What I do remember is that the house was said to be haunted. The house stands on the grounds of what used to be the Central Ohio Lunatic Asylum, which burned to the ground, along with many of its inhabitants, in 1868. In his short story “The Night the Ghost Got in,” Thurber recounts a moonless evening of ghostly scuffles in the dining room. His mother, thinking the noise was being made by burglars, threw a shoe at the neighbors’ window to alert them. Then she “suddenly made as if to throw another shoe, not because there was further need but, as she later explained, the thrill of heaving a shoe through a window glass had enormously taken her fancy.”

It’s here, in his autobiographical mode, that Thurber is most at ease and most easy to read. Once hailed as the successor to Mark Twain in American humor, Thurber isn’t of the spontaneous ha-ha-ha genre. His style is more of a gentle ha that builds up from a smirky exhale. He lets his characters get the laughs, but all the time you know that there’s a skilled hand at work, priming you for what’s coming. For example, in “The Car We Had to Push,” another one of Thurber’s many autobiographical short stories, he writes about “the Get-Ready Man,” a geezer on a mission, patrolling the neighborhood in his Red Devil car and warning people that the end of the world is coming:

His startling exhortations would come up, like summer thunder, at the most unexpected times and in the most surprising places. I remember once during Mantell’s production of “King Lear” at the Colonial Theatre, that the Get-Ready Man added his bawling to the squealing of Edgar and the ranting of the King and the mouthing of the Fool, rising from somewhere in the balcony to join in. The theatre was in absolute darkness and there were rumblings of thunder and flashes of lightning offstage. Neither father nor I, who were there, ever completely got over the scene, which went something like this:

Edgar: Tom’s a-cold. –O, do de, do de, do de! — Bless thee from whirlwinds, star-blasting, and taking… the foul fiend vexes!

(Thunder off.)

Lear: What! Have his daughter brought him to this pass? —

Get-Ready Man: Get ready! Get ready!

Edgar: Pillicock sat on Pillicock-hill —

Halloo, halloo, loo, loo!

(Lightning flashes.)

Get-Ready Man: The Worllld is com-ing to an End!

Fool: This cold night will turn us all to fools and madmen!

When I first read this passage, I actually laughed out loud. If humor is concision, Thurber’s a master. He has a touch-and-go quality about his writing that lets him float from curious incident to curious incident nonchalantly, even passively. Just like his drawings, his writing has an apparent effortlessness, even though Thurber was always painstaking in his work. But on the surface, the humor is light and the stories are real — with just the right touch of Mittyesque fancy.

Even as a Columbus native, I’ve only recently come to appreciate Thurber’s work. I had read his works intermittently in childhood, and I’d been to the Thurber House many times after the young writers’ workshop. For several years in high school, I submitted some poetry and fiction to the teen literary journal published by the Thurber House, and after being published a few times, worked briefly during my senior year for the selection committee. Even then, we often met, not in the Thurber House, but in a neighboring house. And we were discussing our own work, not Thurber’s. But a few months ago, with some spare time and renewed curiosity, I wandered back to the Thurber House and into Thurber’s work again. Meg Brown, Director of Children’s Education at the house, took me around and pointed out some of the highlights: the mixed gas and electricity lighting that made Thurber’s grandmother fear that the house was “leaking electricity,” pictures of the infamous family dog Muggs, described in Thurber’s story “The Dog that Bit People,” Thurber’s original Underwood №5 typewriter, and football and literary memorabilia from The Ohio State University dating to Thurber’s time there. Our last stop on the tour was Thurber’s room. In it, there’s a tiny closet, the interior of which is scrawled with the assertive signatures of authors who have given readings at the Thurber House over the past few decades. It’s the Wall of Fame. I couldn’t help thinking that it was rather crowded already, and that someday soon there will be no more space to inscribe oneself in permanent Sharpie.

The wall is an unlikely but apt representation of Thurber’s legacy of essence, not substance. His essence still lurks around the Thurber House, where writers of all ages and experiences go to learn and work and share, but the substance of his work, though far from lost, is increasingly forgotten. Thurber wrote once: “The sound of a great name dies like an echo; the splendor of fame fades into nothing; but the grace of a fine spirit pervades the places through which it has passed, like the haunting loveliness of a mignonette.” His name and fame have receded in our national consciousness. His most famous writing is remembered mostly in its lackluster film versions dissociated from his name, and his comics, though iconic as representations of the New Yorker tradition, have in that distinction lost the identifier of their maker. Thurber’s case is a lesson in permanence: memory is fickle, and public memory is finite. In some ways, it’s unfortunate, because there are many writers and artists like Thurber, half-famous and half-forgotten, and many who never got the fame they deserved in their own time. But in other ways, it’s a blessing. The audience is smaller but more intimate, and the work holds all the intrigue of initiation into a (somewhat) secret society.

Images courtesy of The New Yorker Collection at The Cartoon Bank.