Review: “Knot Knot”

By Staff Writer Alice Xu

Walking into the Lucas Gallery for Alexis Foster’s senior thesis exhibition, “Knot Knot,” I was struck by the warmness of the room. Featured in April, “Knot Knot” used a visual language to examine elements of African American history typically conveyed through oral tradition. In a room of brown materials from sand-skinned fabrics draped around the upper corners of the entrance to wooden floors, Foster works primarily in the interaction of colors with emotionally-dense objects. Drawing inspiration from courses on African American literature, art, and politics at Princeton, “Knot Knot” looks closely at topics like slavery and rural ghettoes.

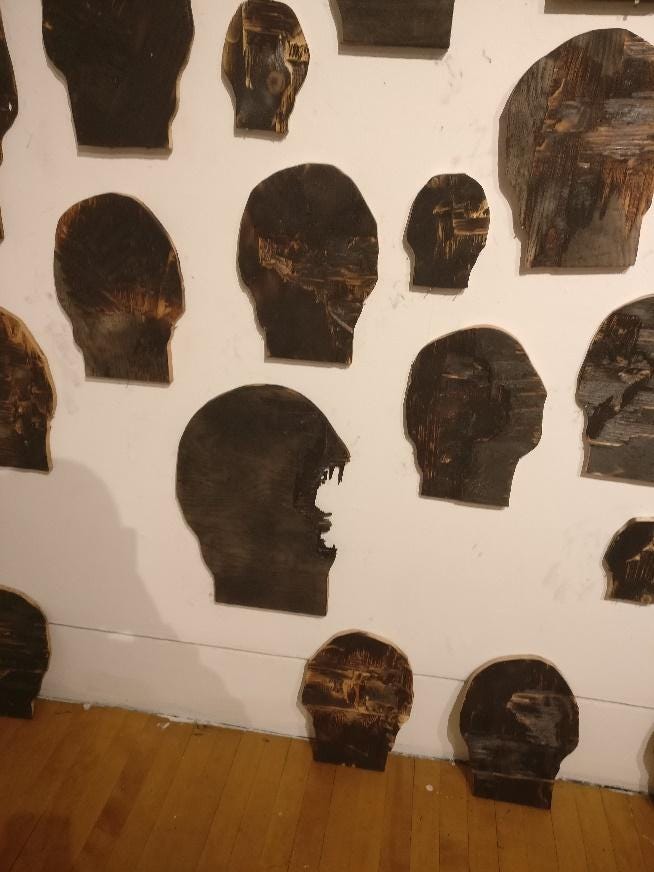

Gazing at the pieces, I was perhaps most intrigued by Foster’s attention to the quotidian. On the left and right were slabs of wood meant to resemble the faces of people. Rather than using common techniques such as sculpting to create them, Foster uses burnt ash wood. Foster indicated, on the Lewis Center for the Arts website, that the burns “[represent] the idea of burning in effigy.” As a result, she attempts to “burn” the caricatures and other harmful representations of blacks. She further reinforces this idea through the few faces that hung between the knotted ropes with pennied faces, where “DIRT” was written on gold cellophane taped to them.

However, through the variety in sizes and shapes, and through the texture of the wood itself, Foster gives each face a personality despite the lack of directly anthropomorphic features. In doing so, Foster criticizes the caricaturization and depersonalization of blacks in literature and media.

As I continued to look around the room, I noticed that on the left side of the room there was a cluster of multiple items: a wooden crate brimmed with objects like gloves, chain links spilling over, pennies pooling from a broken piggy bank. Most notable, though, was a black board leaning against the wall with chalked words like “How do I make my claim to ethnicity authentic”, “misuse/dismantle”, and “Re-Memory”, a phrase which is likely a reference to Toni Morrison’s Beloved. The phrases made me think about the tension that exists between the individual and history, about how we can represent a history given through different mediums. Through these works, Foster questions what it means to explore a history “[intertwined]” with one’s identity.

What I found myself most drawn to, though, was the mural made of rope. The entire front wall, first visible to an entering viewer, was nearly covered in thin pieces of rope weaved over each other. It stood in contrast with the adjacent wall of knotted ropes, connotative of lynching. Foster created three circles on the wall, leaving the left and right circles entirely empty, flanking a circle of rope with an empty rim. Juxtaposed with the knotted ropes, the thinned and unravelled mural stripped power away from objects commonly associated with violence.

As I dragged my eyes down to the bottom of the mural, the four ropes led into the center of the room where a wheelbarrow stood all alone. Despite its lonesomeness that emitted a sense of finality and quietness, it seemed to hold the burden of an oppressive history as it held the portions of the four ropes yet to be unravelled–a history continuing to be unpacked. Indeed, Foster’s “Knot Knot” is an exhibition that engages viewers with its probing of African American history, unravelling their expectations and tying them anew.