What We’re Loving: New Staff Edition 2018

Ask anyone who knows me, and they’ll tell you — I can insert “The Semplica-Girl Diaries” (October 2012) into any conversation. I’ve read a story a day for the past two years, and this one is my favourite. It achieves the highest writing goal in my opinion — emotional resonance. It’s both a captivating read and a lesson in craft.

“Semplica-Girls” is told through the diary of a middle-class father. This allows the reader a window into the protagonist’s soul and quickly establishes him as a sweet, fumbling dad. He’s achingly human, reflecting on his tiniest failures like forgetting to write in his diary immediately after vowing to write every day. The dynamic between the family members is also poignant. When his daughter Lilly says she doesn’t want to have a birthday party, the father asks if it’s because she’s embarrassed of their home. She starts crying. Although he can’t afford it, he starts considering buying an expensive gift she wanted.

I’m endlessly impressed by (and trying to emulate) Saunders’ indirect storytelling. It’s his smallest details that strike the reader’s core. For example, when the main character picks his kids up from school, their car’s bumper falls off. The history teacher helps pick it up, ‘saying, he too once had car whose bumper fell off, when poor, in college.’ This tells us that the main character is still stuck in the economic condition others his age experienced in college.

“The Semplica-Girl Diaries” is ostensibly a dystopian tale about the extent of depravity and commercialisation humanity can fall to, but it’s the ‘mundane’ story of a father’s yearning to provide for his family and his endless optimism in the face of pathetic situations that stays with me.

— Ashira Shirali ‘22

Adam Grant tweeted this image with the caption, “We don’t see things as they are — we see them as we expect them to be.” Perusing his feed in search of pithy quotes like this, I’m never disappointed: as of October 17, 2018 at 5:20pm, Grant has tweeted 3,313 times, and all of them are both enlightening and entertaining. Grant’s an organizational psychologist, and, if you’re ever in Philadelphia, you should definitely try listening-in on his Wharton lectures; or, if you have 35 minutes to spare, tune into his WorkLife podcast for analyses of general #lifehacks. But, if you’re lazy like me, and prefer punchy doses of wisdom as opposed to distilling that wisdom yourself from impossibly long and/or boring entities, I highly recommend Grant’s Twitter feed. His tweets range from moral nudges such as, “Along with intellectual curiosity, we need interpersonal curiosity. Taking an interest in other people is the beginning of empathy,” to musings on current events like, “When a man argues with an umpire, it’s passion. When a woman does it, it’s a meltdown. When a black woman does it, it’s a penalty. #DoubleStandards #USOpen #Serena.”

I love Grant’s twitter so much that I check it regularly — Even. Though. I. Don’t. Have. A. Twitter. Now that’s dedication. So, you can either join his 198K Twitter followers, or just stalk his feed like me; either way, Grant’s a pleasure to read not just because I agree with what he thinks, but because I’m intrigued by how he thinks — and how he makes me think.

P.S. If that previous sentence sounded at all wise to you, it’s because I tweaked one of Grant’s tweets! That’s right, he’ll even make you sound smarter.

— Priya Vulchi ‘22

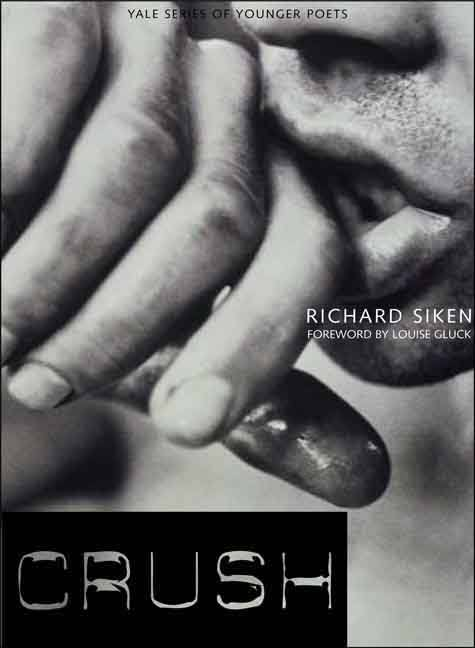

Sunlight pouring across your skin… / The light is no mystery, / the mystery is that there is something to keep the light / from passing through.

These are the opening and closing lines of “Visible World,” a poem in Richard Siken’s collection Crush (2005). The word crush describes an attraction to someone, but also suggests an immense pressure, one which often breaks the object of its force. Both aspects of this word come together in Siken’s subject matter as he (almost) exclusively uses “we,” “you,” and “I” throughout his poems, each of which is crushed by the others. The exclusive use of these pronouns makes every line connected to one’s sense of being and body.

This connection to the self comes through in Siken’s use of images. In “Visible World,” he does not just describe sunlight streaming into a room, but the sense of how strange it is to have a body when holding one’s hand up to the light. The idea of pressure comes through in his (often panicked) writing as a train of thought continues, contradicts itself, and repeats. Sentences are crushed between each other, thoughts drowning under the pressure of those surrounding it:

I swallow your heart and you make me spit it up again. I swallow your heart and it crawls / Right out of my mouth. / You swallow my heart and flee.

Siken’s writing captures thought in a way I had only ever seen in stream of consciousness writing. This effect is in part due to Siken’s use of line breaks and spaces to illustrate jumps and connections between the lines, which flows in the same disordered way thought often does.

I was delighted to come across Siken’s writing — Crush is both engaging and beautiful, and reading his poetry is a relief from my own crushed and jumbled thoughts.

— Kate Kaplan’ 22

We live in the Anthropocene. A combination of the Greek word meaning “human” (anthropos, or ἄνθρωπος) and the word meaning “new” or “recent” (kainos, or καινός), this word is, fittingly, used to describe the unofficial epoch dating from the start of significant human impact on the Earth’s geology and biosphere and continuing to this day. The implications of a human-centered planet are as varied as they are numerous — ranging from miraculous technological innovations to dying rainforests and coral reefs, from paradigm-shifting scientific discoveries to dried-out river beds — and their consequences can never be fully extricated from one another.

What is particularly fascinating about, and is perhaps the heart of, the Anthropocene is the endless feedback loop we have created for ourselves — one in which the human experience of the human-created world affects how we further continue to shape that world. This is the theme broached by author John Green’s captivating and oddly poignant podcast, The Anthropocene Reviewed. Each month, Green reviews two facets of “the human centered planet” on a five-star scale (these facets have included everything from Diet Dr. Pepper to cholera, Halley’s Comet to Super Mario Kart, the Taco Bell breakfast menu to the Lascaux Paintings).

In these reviews, John Green, with his characteristically unaffected tone, begins by painting a picture of each object’s place in our history and in our daily lives; quickly, however, and quite fluidly, he dives into the philosophical. Within these twenty-minute monologues, Green manages to find a lens into even the most outwardly common and unassuming things (how many of us perceive Canada geese or the practice of googling strangers as inherently poetic?) that reveals some aspect of the human experience that is always compelling and frequently genuinely moving.

After listening to an episode of The Anthropocene Reviewed, it becomes impossible to take any object, however familiar, for granted. Green brings his listeners to the realization that everything in our world is inextricably placed within an intricate historical and cultural context, and that everything, when viewed with curiosity and attentiveness, can evoke deeply personal revelations about ourselves and about humanity. The world seems more fragile, and fascinating, and complicated, and beautiful with each new update; in short, Green’s podcast equips us to be more responsible and responsive citizens of the Anthropocene.

In the tradition of the podcast itself, I give The Anthropocene Reviewed four and a half stars.

— Mina Yu ‘22

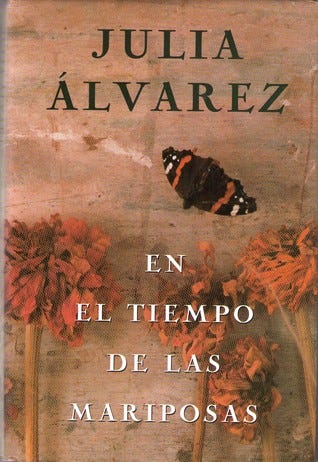

A history told in four voices. In the Time of the Butterflies (1994) by Julia Alvarez, is at once a celebration and an elegy, an imaginative exploration of feminism, resistance, and family. The novel is a work of historical fiction that remembers Minerva, Patria, and María Teresa Mirabal, together lovingly called “Las Mariposas” (“the Butterflies”), who were Dominican sisters and revolutionaries assassinated by the dictator Rafael Trujillo in 1960. The three sisters’ voices alternate chapters, each on their own path to revolution and, inevitably, death. The fourth narrator is Dedé Mirabal, who was the only surviving member of the Mirabal family when Alvarez wrote the novel in 1994. While her sisters’ voices propel the tragic story forward, it is Dedé’s retelling of their lives that is the mournful frame of the novel. This elegant structure, which pushes three parts forward and one part back, holds together a history that can only be told in pieces, a tragedy that devastated a family and awakened a country to its own devastation. “In the Time of the Butterflies” is a meditation on what it means to sacrifice and what it means to survive, asking the reader, over and over again, “What would you be willing to die for?”

— Chaya Holch ‘22

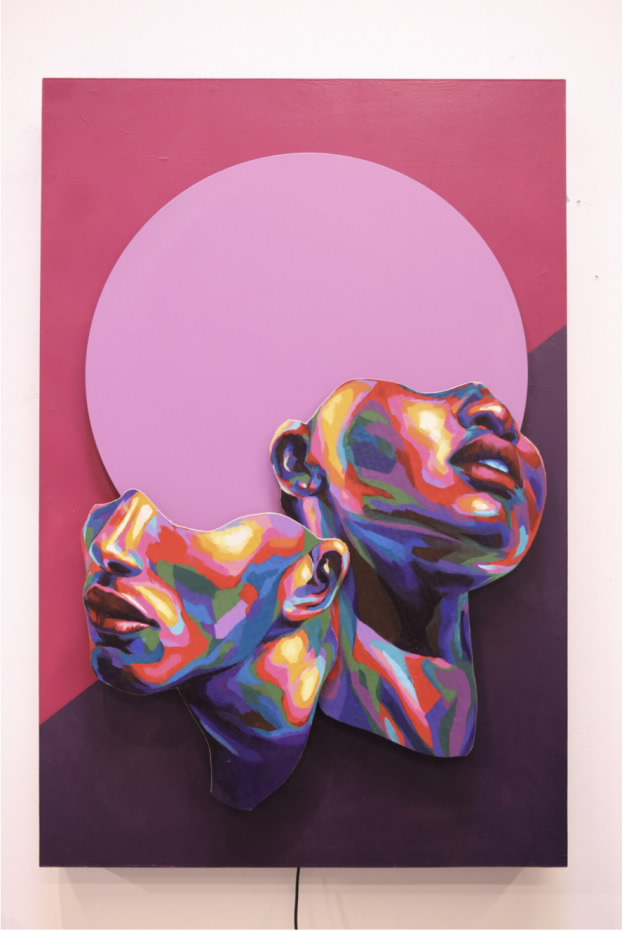

Upon first glance of “Between the Hues,” an art series by Denver artist Thomas “Detour” Evans, the dynamic use of abstract shape, the impressive construction of shading, and the complex use of vibrant colors all stand out as key features that Detour uses to bring life and personality to the otherwise anonymous subjects that are missing a half of their face, and thus whose identity, context, and story is untold. Yet, beyond the stunning visual components of Detour’s pop art paintings, they also contain a hidden treasure. If one were enter one of his exhibits you may see people participating in a behavior that is traditionally prohibited in art displays: touching his art. Detour adds a unique interactive component to his paintings by allowing the audience to touch different parts of his paintings in order to create music. Detour uses a mixture of traditional art forms and technology to create an expression of urban culture and minorities. The images and sounds presented in this mixed media art represent the beauty, intricacy, and complexity of certain communities, and sometimes tackle the serious issues that affect these communities. Detour fully engages both the eyes and ears of his audience, who get an encapsulating experience with the art, and build a connection with the issues of urban culture.

— Savannah Krueger ‘22

Emily Wilson released her new translation of the Odyssey (2017) late last year to great and deserved fanfare — she was the first woman to translate Homer’s epic into English. She gives the work a fresh and eminently readable treatment in quick iambic pentameter, in contrast to the verbose phrasings of Robert Fagles’ popular translation. The epithets for which Homer is so well known — memorably rendered by Fagles as “rosy-fingered dawn” or “crafty Odysseus” — are helpfully varied throughout Wilson’s interpretation, reflecting an ambition to take the reader back to the varied meanings of the Greek.

Her ambivalent take on Homer takes the text in radically new directions. I will focus here on her line of introduction to Odysseus’ narrated flashback of his trials over his decade-long voyage home in Ithaca that lasts for four of the Odyssey’s twenty-four books. While Fagles and Fitzgerald used this preface to wax praise of Odysseus’ craftiness and narrative prowess, Wilson calls him out for mendacity: he is “the lord of lies.” Even rational Greek philosophers found it painful to question or refute Homer. The hagiographic tales of Odysseus that have filled shelves since George Chapman’s 1616 translation of the Odyssey — a lineage that continues through Fitzgerald and Fagles — are rejected by Wilson. Perhaps her translation is the declaration that our modern age has finally exited these insecurities of both the Greeks and the Victorian poets that glorified Chapman and invited the glowing tales spun in Fagles’ edition. Wilson’s translation of the Homeric epic, then, is truly revolutionary. It will be an essential installment of both the quality and ideology English speakers will use to understand of Homer and Odysseus for years to come.

— Isaac Hart ‘22

In a desperate search for an appropriate graduation gift from my erstwhile, romantic English professor, I spent long hours in the back aisleways of my local Barnes and Noble, rifling through poetry books in a chaotic search for new and refreshing talent. Just as I was about to sadly settle for nothing more than the wittily written, yet sadly expected Sherman Alexie collection, I stumbled upon Songs with our Eyes Closed (2017), a book of poetry by first-time author Tyler Kent White. Admittedly, it wasn’t the cover that caught my attention; the plain white background and mutedly colored words were not enough to attract my frantic gaze. What I did initially fall in love with was the meaning of the title itself. The words Songs With our Eyes Closed evoked a sense of dreamy wonder in me that immediately set my romantic heart racing. And oh did the poems inside not disappoint. From the uncapitalized letters, to the way the titless poems flowed together to create a beautiful tapestry of words, each page found me increasingly enthralled, to the point that I was crouched in that musty corner for an hour. What astounded me most was that taken individually, no one part of his work was anything special. The word choice was not particularly spectacular, and one could argue that the word “love” could have been spared a few more times. The structure was also typical, standard stanzas with the occasional foray into abstract spacing. Even the poems themselves were quite similar in tonality to other poetic greats who had come before, such as Rumi. Yet I didn’t care about that in the moment. What I loved about White’s poetry was how it made me feel. For example, the line “i have come to realize why homes settle and sigh/when the weather changes and we are asked/to withstand another storm on our own” evoked a sense of nostalgia in me that my 18 year old self had no right to feel. The phrase “there are lesser men that live inside of me. i know. i have been them” had me rocking back and forth in equal parts shame, awe and recognition. And the motivationally witty “the earth did not ask/why me?/when her plates shifted and/ her fault lines stretched and/her contours/pushed/and pulled” propelled me to impulsively buy two copies of the book instead of just one.

— Nancy Diallo ‘22

You notice a woman ahead of you on the streets passing out fliers. As you approach her, you purposefully walk on the side of the road farthest away from her, thinking that she’s probably advertising the latest brand of some designer brand perfume. But she runs to you and hands her flier over anyway, a desperate expression clouding her face. She says to you, “Please call if you see her.”

Please Look After Mom (2011) by Kyung-sook Shin is probably one of the most universally relatable Korean novels published in contemporary literature. The former because we’ve all experienced losing someone close to us, and the latter because the way in which Chi-hon, our protagonist, initially expresses her grief over her mother’s disappearance is inherently Korean in that her emotions are strongly bound to her sense of duty and guilt towards her mother. While American culture puts emphasis on the parent raising the child, in Korean and other East-Asian cultures, it is also an essential part of the piece that constitutes “family” for the child to repay the parent and take care of them in old age. In fact, Korean media often portrays this kind of tradition as the child’s moral obligation.

What makes the novel so radical, however, is that, Chi-hon is portrayed not as the perfect daughter who prioritizes her mother over her own life, but as someone who is initially repulsed by the idea of being confined to this tradition. In fact, when her mother disappears at Seoul station, she and her siblings even treat their mother simply as one thing on a long list of entries on their to-do lists. However, when Chi-hon finally realizes that her mother may never come back to her, she is driven by her raw emotions and love for her mother. This, in combination with the second person that Shin uses so masterfully, pulls the reader into the story, revealing to us the universality of familial loss as well as the key to a truly meaningful life.

— Nancy Kim ‘21

There’s nothing quite like walking a mile in someone else’s shoes to make you see how much of your own road still lies ahead. In the spring of my senior year of high school, a newly published memoir appeared in a package on my doorstep, courtesy of a Jewish summer program in which I had participated. I didn’t know it at the time, but Ilana Kurshan’s shoes were exactly what the doctor ordered.

If All the Seas Were Ink (2017) is a testament to the power of learning and relentless self-improvement as means of emotional healing. Kurshan opens with a matter-of-fact depiction of heartache. The stereotypical Harvard and Cambridge educated serious young woman, she suddenly found herself madly in love, marrying a man within a month of meeting, uprooting her life in America to move to Israel with him, and divorcing less than a year later. She was completely lost and alone in a foreign land.

The book traces Kurshan’s next steps as she grasped an unusual lifeline: a book club of sorts called dof yomi, a religious practice in which one studies the Talmud by reading one page a day for seven and a half years. Poignantly weaving the narrative of her life out of the metaphors and language of the Jewish texts she encountered in congruence to it, Kurshan thrusts readers into her world. I grieved along-side her as she grappled with the memory of adolescent eating disorders and I shared in the selfless joy of her eventual motherhood. Through sheer force of will, she learned to see beauty around her, and by imparting this experience to me, so did I.

— Marie-Rose Sheinerman ‘22

Notes from the Underground (1864), as far as Dostoevsky goes, is accessible, relevant, and most importantly, short. Nevertheless, it is not an easy read. As I am now — an amorphous ball of wet clay — unsure of what I want to do with my time at Princeton (and all the time afterwards), I was stirred by Dostoevsky’s musings on choice.

The first question raised by “Notes” is that of free will. In an entirely self-contained dialogue/diatribe/rant, the narrator — calling himself the “underground man” — challenges the idea of scientific determinism, I think, rightly so. It is a tad absurd to assert that the laws of nature govern every decision we make. Yet, the underground man is an outcast. He is awkward, impolite, and deliberately rude. He justifies his erroneous behavior as a refutation of determinism and exertion of free will. Free will, as demonstrated by the underground man, manifests itself as antipodal to self-interest, often going as far as self-sabotage.

As the novella progressed I realized that there were some edifying qualities in the underground man’s philosophy. Aside from irrationality in the form of ribaldry, the underground man also defied determinism with gratuitous empathy.

In one scene, this social pariah encounters another: a prostitute. Breaking from his characteristic miserliness, he goes out of his way to convince this girl to reconsider her choice of work, affirming that, in fact, she has agency. Undoubtedly, her situation improves, elevated by a newfound conviction in free will.

Dostoevsky tends to deal in extremes. No one is likely to see eye-to-eye with the underground man, but he makes some compelling points. Whatever it is I end up doing in four years — “right” or “wrong” — it will be of my own volition.

— Samuel Himmelfarb ‘22

Recently, with the trees turning gold and crimson and the crisp autumn air infused with the scent of ripening leaves, I have found myself longing for the comfort and nature of my beautiful home in Oregon. There is nothing quite like fall in the Pacific Northwest; it’s all the minor details that make it so irreplaceable, from the campfires with friends within the arms of pines and evergreens, to the smiles and hugs exchanged between the steady stream of bodies seeking refuge from the bitter cold within independent coffee and tea shops. I am fortunate to have found a means of reproducing some of the feelings and memories associated with my home state through Sufjan Stevens’ masterpiece of an album, Carrie and Lowell (2015). The album, part of which was recorded in Oregon, subsists of Stevens’ soft, whispery singing voice layered over an acoustic background composed of gentle guitar picking and the occasional piano accompaniment; together, the hushed instrumentation creates a slightly folksy, very whimsical feeling that seems to perfectly encapsulate the spirit of Oregon. In fact, the album was primarily inspired by family trips to Oregon Stevens would take with his now-deceased mother Carrie during his childhood. There is a strong sentimental, almost innocent childlike feeling, evoked by lyrics such as: “light struck from the lemon tree…”

Yet despite the lighthearted, almost nostalgic atmosphere within the album, the lyrics add somber undertones, addressing themes of death, loss, and pain all throughout the album, generating a very bittersweet tone: “what’s left is only bittersweet//for the rest of my life, admitting the best is behind me.” Stevens himself stated that writing and recording the album helped him process his mother’s death, and provided a sense of closure to this chapter of his life.

— Cameron Lee ‘22

I’ve been following The Internet since late 2016, ever since my sister introduced me to their debut album, Ego Death (2015). Back then, it was the album of my summer; Syd’s sweet breathy voice against the heady guitar riffs that filled the car as I drove, windows down, through neighborhood streets, the occasional palm tree-lined road. Their style was just emerging then: an experimental, jazz/funk, slow groove, sexy R&B vibe, somehow reminding me of what the LA underground scene would have looked like back in the 90’s, but with a little more electricity.

Hive Mind (2018) was released this past summer and quickly became the staple of those three months I spent at home, or the park I used to visit as a child, or the passenger seat of the car (my sister at the wheel), and here setting up my dorm the first afternoon of September. The Internet’s style in Hive Mind has changed. The songs are lighter, the production less elaborate and grandiose, but there’s a sense of maturity: a sureness of the band’s own place musically that wasn’t there in their previous albums. They still retain the image and sound of a slightly jazzy, slightly R&B, slightly funky, genre-crossing, ragtag group of musical friends (or musical geniuses?) And they’re not a band that’s tied down to their own musical style. With Hive Mind, they’re willing to continue exploring and developing new sounds, innovating what already works for them as a group. The simpler version of their old sound from Ego Death allows them to highlight in Hive Mind the strongest aspects of their music: Syd’s lilting/suggestive vocals, Steve Lacy’s impressive guitar work, the effortless R&B-soul-hip hop-fusion vibe that show through every unique track they put out. I played this album on repeat in the car, in bed, at my desk, on a blanket outside. It reminds me of California, and the ease with which life seems to move back home. To end, I’d like to highlight a few of my favorite tracks from this album: It Gets Better (With Time), Hold On, Next Time/Humble Pie, Come Over, Stay the Night, Wanna Be…let’s be clear though: this album functions best as a whole, played through (in order). It’s a 57-minute reminder of summer at its best: intense, yet laid-back. Dreamy, and still vibrant.

— Noel Peng ‘22