Friedrich Hundertwasser: “I Give Houses Back to the People”

By Staff Writer Simone Wallk ’21

Each of us crafts home in some way, choosing and designing the spaces we inhabit to be comfortable, nurture us, and reflect our values. Home is a safe place, a psychological haven where identity is built and intimacy is fostered. I was challenged to think deeply about the importance of home as a reflection of values upon visiting the Kunst Haus Wien, a museum dedicated to the work of Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928–200), an Austrian painter, philosopher, and architect. The sensory experience of the Kunst Haus is powerful alone; its floors roll and buckle to imitate the swell of earth, trees grow out of its windows, creating a fragrance of soil, and most surfaces are decorated with mosaics or recycled glass. And yet Hundertwasser’s aesthetic choices are not merely bold. They embody a complicated philosophy of environment and aesthetics grounded in the claim that home itself is self-expression.

Today, seventeen of Hundertwasser’s creations remain: one-of-a-kind buildings with roof gardens, courtyards, tenants’ drawings on the walls, and significantly reduced carbon footprints. Hundertwasser’s oeuvre is at the intersection of art and activism, making statements against conventional architecture that separates the built and natural environment. His work, in its shameless utopianism, provides a model for environmental architecture today to engage with the concepts of home, freedom, and aesthetics.

“I want to show how basically simple it is to have paradise on earth,” wrote Hundertwasser in 1975. In his art and philosophy, Hundertwasser was boldly aspirational. His chosen name — Friedensreich Hundertwasser, which literally means “Peace-Realm Hundred-Water” — is symbolic of his unashamed attempts to express his ideology through his very being. His philosophy aligns well with Deep Ecology, as he regards the living environment as worth protecting regardless of its utilitarian value. The natural world also had spiritual resonance to Hundertwasser; “the brook, the river, the swamp, the riverside wetlands as they are, the way God created them, must be sacred and inviolable to us.” Despite the urban location of the Kunst Haus, I experienced Hundertwasser’s respect for nature in the building’s natural ventilation and light, the presence of plants and waterfalls, and a spacious courtyard.

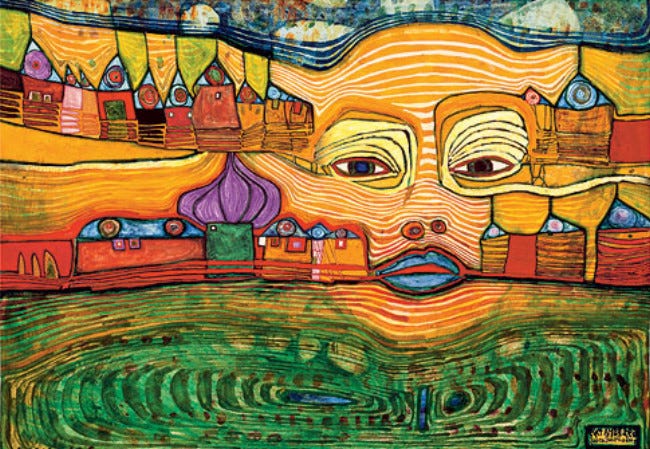

Human unity with the environment is apparent in Hundertwasser’s paintings, too, which he created while travelling around the world by ship. In Irinaland, a 1969 work depicting his Bulgarian lover, a woman’s visage becomes one with the landscape, her skin taking on the creases of the hills, her head crowning on the horizon. Her eye sockets, heavily outlined in a dark orange, resemble the squat homes that line the hills. With brightly colored onion domes and kaleidoscoping windows, this work is one of many that foreshadow Hundertwasser’s trademark architectural styles.

Irinaland presents an individual as her landscape, reflecting and shaping the outer environment, demonstrating how Hundertwasser viewed the individual self as inseparable from its conditions. In a drawing from 1972, Hundertwasser outlined this philosophy, which he dubbed “The Five Skins.” Home, to Hundertwasser, is one of five skins possessed by man: the literal epidermis, clothing, housing, social identity, and Earth. The Five Skins are embodied by Irina, whose many skins blur into the outermost planetary skin — the Earth. Human and place become one in this vision of the Five Skins.

Hundertwasser’s attitude towards the third skin, housing, was shaped by the architecture movements of his time, a linear, rationalist style, including urban grid systems and standardized, industrially produced housing units — itself a response to the ornate fin-de-siècle style. Hundertwasser attacked the popular architect Adolf Loos in his manifesto “Loose for Loos,” describing the straight lines of modern architecture as oppressive: “The straight line is godless. The straight line is the only uncreative line. The only line which does not correspond to man as the image of god. The straight line is a true tool of the devil…” Straight lines, to Hundertwasser, represent inorganic uniformity, hampering mental health, creative agency, and connection with surroundings. I appreciate his sensitivity to the contrast between home as an embodiment of the self and the standardized, assembly line structures of the Loos era. And this critique is all the more interesting with the religious language Hundertwasser uses, indicating that he might find something spiritual in the organic, democratized homes he strove to create.

Hundertwasser’s attack on the straight line is ideological and shocking in its language. “Loose for Loos” is rife with references to “reparations,” and Hundertwasser makes analogies between Hitler and Loos. This extreme rhetoric, particularly coming from Hundertwasser, a Jew who survived the Holocaust by pretending to be a Catholic child, underscores the emotional roots of his views of housing. Hundertwasser’s analogy between Loos and Hitler is further evidence of his radicalism — he views the impact of poor aesthetics as grave as loss of life en masse. He is enraged by the psychological and physical consequences of linearism, creating a “deadly monotony:”

The diseases of people confined in sterile residential complexes flourish in the deadly monotony. Rashes, ulcers, cancers and strange manners of death all occur. Recovery in such buildings is impossible. Despite psychiatry and health insurance.

There are increasing numbers of suicides in the satellite towns, and countless suicide attempts. These are women who cannot get out during the day like the men. We could spend hours listing the miseries which began with Loos.

The nihilism of the interned expresses itself through a decline in the desire to work, a decline in production, as psychiatrists and statisticians can surely confirm. For unhappiness, too, can be quantified in figures and money.

These ideas, presented in 1968, predate modern scientific conclusions that the materials used for industrial construction — lead, asbestos, and all those we don’t yet know about — are toxic for the human body. His rhetoric is at once convincing and jarring; it is quite unusual to philosophize about architecture with such emotional urgency, and yet fitting to the centrality of home to our lives.

Here and otherwise, Hundertwasser is careful to appeal to the profit-minded who might hear his manifestos. By framing cultural unhappiness as a financial loss, or by quantifying the benefits of ecological aspects of his housing, Hundertwasser appealed to municipal officials and architects who were essential to realizing his projects — his idealistic vision was successful despite his stubbornness and refusal to compromise on his principles, and only because the artist partnered with trained architects and Viennese officials.

Anger aside, Hundertwasser suggests a realistic solution. Rather than tearing down modern Europe’s prison-like constructions, he calls for modification of the serially produced buildings that Loos inspired. He believed in aesthetic solutions to social problems, but also took an activist approach, urging a boycott of “slave cages” and encouraging “architectural change through the visitor,” who might pour paint on its austere walls or “put a nice hump of plaster… on the wall.” While Hundertwasser pursued these activist tactics, even giving speeches in the nude as a statement about the importance of the third skin, he took on an additional role as an “architecture doctor,” curing the ailments of unsustainable, uniform structures. Lacking formal training as an architect, he approached functionalist buildings with an eye towards improvements that would reduce their environmental impact and beautify their appearance, doctoring residential buildings, industrial factories and plants, toilets, and public buildings. His architectural doctoring is both activism and art, a melange of the political and aesthetic that entangles once functional questions of design with their ethical implications.

The moral imperatives for Hundertwasser’s crusade included environmental unsustainability, uniformity, and impersonalization. He wrote,

“our houses have been sick…. If you let windows dance by designing them in different styles, if you allow as many irregularities as possible to appear or happen in facades and interiors, houses will recover. Houses will begin to live. Every house, however ugly and sick, can be cured.”

This optimism served Hundertwasser well as he crusaded against frustrated municipal building officials, whose codes and regulations he urged tenants to disregard.

And cure houses, Hundertwasser did. While his projects experienced significant backlash, particularly from the Viennese government, his buildings are remarkable realizations of his moral and political stances.

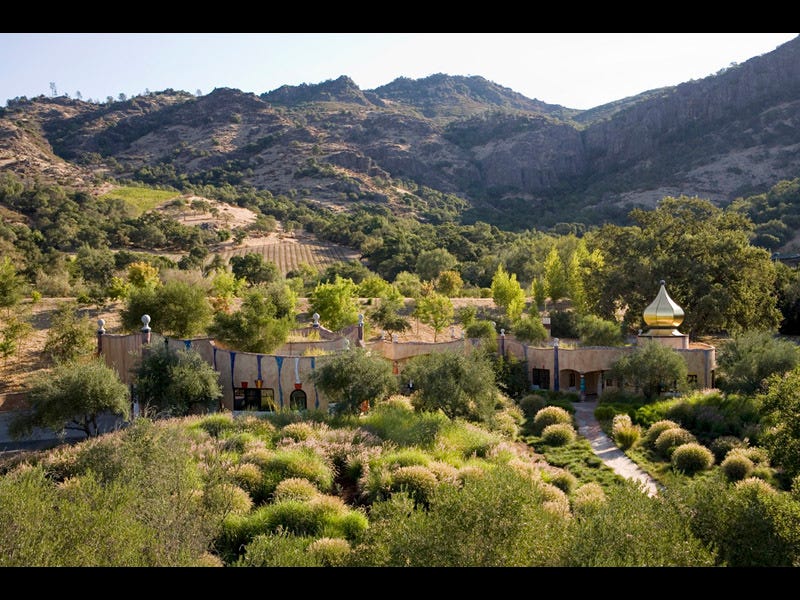

Hundertwasser’s central personal project was the rehabilitation of a dairy farm in New Zealand into a habitable estate. On the farm, he cultivated over 60,000 trees from around the world, a statement against monoculture. The roofs were covered in soil and plants, nearly blending in with the surrounding landscape but for a few windows peeking out. With a humus toilet and rainwater collector, Hundertwasser’s personal home embodied the environmental values of his name.

Beyond his personal project, Hundertwasser’s panacea for the ills of modern housing included two central components: Window Rights and Tree Tenants. The former was a statement of the individual’s architectural autonomy, an argument against the dichotomy between architect and tenant in favor of radically democratized construction and decoration processes:

A person in a rented apartment must be able to lean out of his window and scrape off the masonry within arm’s reach. And he must be allowed to take a long brush and paint everything outside within arm’s reach. So that it will be visible from afar to everyone in the street that someone lives there who is different from the imprisoned, enslaved, standardised man who lives next door.

In customizing housing, Hundertwasser argues that individuals can find a means of self-expression more healthy than coping with modern standardization through “alcohol and drug addiction, exodus from the city, cleaning mania, television dependency, inexplicable physical complaints, allergies, depressions and even suicide, or alternatively with aggression, vandalism and crime.” He speaks to the freedom to create place that was stronger just a few generations ago, and in calling agency over housing a “right,” democratizes the bourgeoise associations with decor and architecture.

More practically, Hundertwasser advocated for Window Rights to be supported by the state, which might “provide financial assistance and support to every citizen wishing to undertake individual alterations whether to outside walls or indoors.” Here Hundertwasser expresses a class-consciousness latent in other elements of his writing, where he often praises the conditions of slums as “preferable to the moral uninhabitability of utilitarian, functional architecture. In the so-called slums only the human body can be oppressed, but in our modern functional architecture, allegedly constructed for the human being, man’s soul is perishing, oppressed.” Not praising poverty itself, but the organic and un-planned dwelling of slums, Hundertwasser idealizes home creation as a spiritual act, while inadvertently romanticizing the conditions of the urban poor.

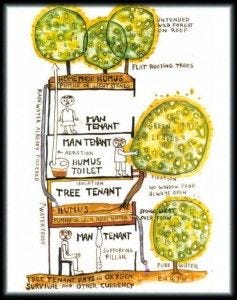

As an extension of the Window Rights principle, Hundertwasser organized “Tree Tenants” in 1974 for the Triennale de Milano. By planting twelve trees inside an apartment building, with their limbs extending out the windows, he hoped to address the plagues of urbanism: air pollution, lack of oxygen, visual monotony, and the sterility of high rises. Cleverly, he proposed that “the tree tenant pays rent in a more valuable currency than a human tenant” through supplying oxygen, regulating climate, absorbing sound, “dispensing beauty,” acting as curtains, hosting butterflies and birds, and improving the mood. All of this, to Hundertwasser, is “a symbol of reparation towards nature” through the integration of natural and inhabited environments.

***

In Vienna, exploring the Kunst Haus, I found Hundertwasser’s philosophy brought alive in a union of the built and the natural: sun-soaked galleries, stray leaves from tree tenants carried through open windows, a vast courtyard embedded in an industrial block off the Dampfschiffstraße. Hundertwasser’s manifestos are lofty, utopian declarations, but his creations ground radical claims in reality, realizing the democratic, ecologically sound architecture he proposed.

A primary example is the Hundertwasser Haus, a Vienna landmark. It was constructed as a public housing project, yet it defies the stereotype of utilitarian low-income housing. Rather, the building is one with its neighborhood, including cafés and office spaces, a communal courtyard, and an abundance of greenery. Residents testify to the extraordinariness of the house, saying:

Caroline: It [the house] is splendid, yeah? Actually it lives, it is alive, and it is so welcome, it is actually a State project, [almost] where the thought was, like in a museum, that it will hopefully be entertaining too. So it’s living, and the tourists downstairs who look at it… that’s normal, I’d say.

Alex: There must be something about this place. . .if you don’t like a picture, you walk past it with your eyes shut If you don’t like music, you turn it off. . . . But you always have to live with architecture. Hundertwasser knew that, [he] knew how you must feel well there. It’s not psychological, or psychoanalytical, but psychosomatic… (qtd in Peter Kraftl, “Living in an artwork: the extraordinary geographies of the Hundertwasser-Haus, Vienna” in Cultural Geographies.)

The house is dynamic and alive to its residents, an emotional residence complicated by its status as a tourist attraction. Here the ideal and reality blur, as Hundertwasser’s utopian vision is so outlandish as to make itself a curiosity.

It seems especially significant that the Hundertwasser Haus is a public housing project, empowering not only the wealthy to live in personalized, artistic spaces. In fact, while Hundertwasser’s aesthetic might seem bourgeoise or artisanal, he did not use handmade building elements, but instead repurposed and harmonized industrial elements. It is an example of communal space and creative expression in housing, as residents embellish their walls, socialize together in the public courtyard, and take pride in their colorful dwelling.

Hundertwasser’s works are at once realities and utopias. His creations do not compromise, and in this commitment to principles, I see an inspiration for modern ecological architecture. Movements like zero-waste housing, which seeks to make homes that use renewable energy and contribute positively to the surrounding environment, seem as idealistic as Hundertwasser’s tree tenants — why could they too not become a reality, even at a small scale?

Hundertwasser acknowledged the immense impact that space has on psychology, placing emphasis on the determinism that color, openness, form, and material have on the individual. He embodies the theory of Alain de Botton, author of The Architecture of Happiness:

“We need a home in the psychological sense as much as we need one in the physical: to compensate for a vulnerability. We need a refuge to shore up our states of mind, because so much of the world is opposed to our allegiances. We need our rooms to align us to desirable versions of ourselves and to keep alive the important, evanescent sides of us.”

Perhaps this is why home was so important to an itinerant like Hundertwasser; it grounded him in the truths of his commitment, allowing him to “enter a house as a freeman. Not as a slave.” If only we, too, could cultivate our values through designing living spaces that reify the utopias we wish to inhabit.