What We’re Loving: Fall Break 2018

Mt. Joy (2018), the debut album of the eponymous band, is as much a soundtrack as it is an attitude. It’s a collection of underground anthems for the stony-eyed and weary-hearted twenty-somethings of the world. The band has a noteworthy range. Each song hopscotches from comedic to sappy to supersonic all in one breath, but their breadth is not what sets the album apart. Instead, Mt. Joy’s assortment of unforgettable melodies is an indulgence for the listener. Flaming red and icy blue lyrics combine for a breathtaking emergence into the most private fantasy — to crumple up the world like a pink bubble gum wrapper and toss it to the wind.

At its core, Mt. Joy is what most other stoner indie rock bands think they are. In a word, authentic. Truth rings behind every word that Matt Quinn lets pass through his lips, whether he’s singing about the economics of dreaming or a “doobie smoking Jesus.” “Astrovan”, the first single released by the band, was an unsurprising hit. The song captured the heads and the hearts of a million young dreamers trapped in anonymous college towns, giving them 3 minutes and 6 seconds to live out their Beat-Generation-inspired fantasies.

The powerhouse of the album, however, is the sweetly simple “Cardinal”. The song makes steps toward the “be yourself” message already covered by a million and one other tunes. But Mt. Joy takes a new approach, effective in its novelty. The loneliness of nonconformity is braided into the first chords of the song, an elegy for the red cardinal “too high to fly home for the winter”. The song underscores the easier-said-than-done nature of being one’s self in an unkind world. Yet, as the tempo picks up, and the layers of the song begin to grow, the listener feels the burgeoning seeds of hope take root in their chest.

Corny? Perhaps. But even after the first ten plays of the album, you don’t tire of hearing “all of my favorite people, they don’t march to the beat of your drum” — one of many attitudinal phrases scattered throughout the album, saccharine and simple in all the right ways.

— Andrew Tye ’21

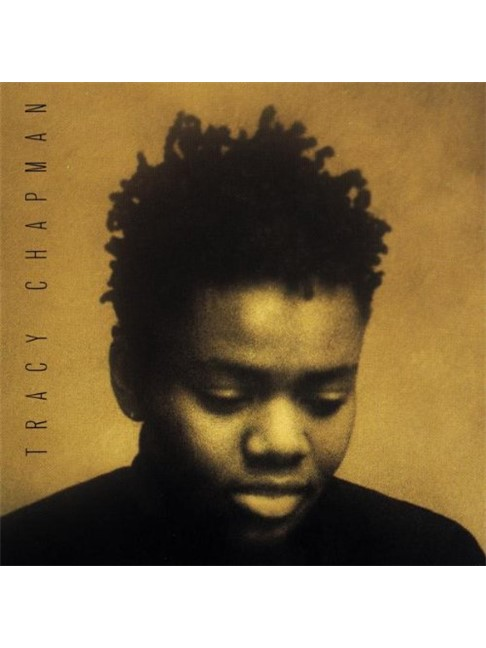

Over fall break, I spent a lot of time with my boyfriend, and through our time together, I have fallen back in love with a song that he introduced me to a long time ago and that has become one of my favorite songs of all time: “Fast Car” (1988) by Tracy Chapman. While it has been decades since African American folk-legend Tracy Chapman first gifted the world with this deep, soulful, acoustic ballad, this song never still fails to encapsulate and resonate with listeners.

The song follows a universal story, one of a young girl stuck in a cycle of poverty, facing familial problems, stuck in the same city, and living the same story. It opens with the lyrics “you’ve got a fast car, I want a ticket to anywhere.” The opening verses continue to paint a narrative of a girl who just wants to escape with her lover to start a new life away from her convenience store job and alcoholic father. It does not matter where they go as long as they get away quickly. Her story is told in to a meditative, lulling acoustic beat that is almost as repetitive as the problems the woman faces and as simple as the life she leads. Through Chapman’s soft, deep vocals, you can feel her calm, yet wounded spirit. Yet, when the chorus strikes, this soft melody is lost to the powerful cry of Chapman’s soulful voice, a faster tempo, and striking instrumental force that contrasts with the aforementioned verses. The chorus represents the high she feels in her lover’s car, driving fast down the highway, escaping her life, and finally finding a place where she felt home. The forceful beat and tempo of the chorus gives off the feeling that we are escaping these problems with her, and through the emotion behind Chapman’s roaring voice we can feel just how passionately this woman wants to be free of her struggles, find a new place to fit in, and finally find happiness. The chorus is the glimmer of hope and joy we see in this grim, broken narrative. In later verses, the melodic beat reoccurs and we learn that the lover she was so optimistic about before has just contributed to the cycle of problems and poverty she has dealt with her whole life.

This has always resonated deeply with me. The desire to drive away and start a new life away from all the pain you’ve faced, that invincible feeling when you’re driving seventy miles per hour with your friends, staring out over the whole city lit up, being with those you love, wanting so badly for that feeling to last forever and to leave all your problems in the past — these feelings are all encapsulated perfectly through Chapman’s voice.

“So I remember we were driving, driving in your car, speed so fast it felt like I was drunk, city lights lay out before us and your arms felt nice wrapped around my shoulder, and I had a feeling that I belonged, I had a feeling I could be someone…” It is a chorus that I will cry out at the top of my lungs whenever I am too stuck in my own problems, and suddenly I am teleported back into my own car with my friends, a place that we often used to bond and find asylum from our own problems and our own lives. For that reason, beyond being a beautiful, powerful song, this song has become so universal and touching for me and for many others.

— Savannah Krueger ’22

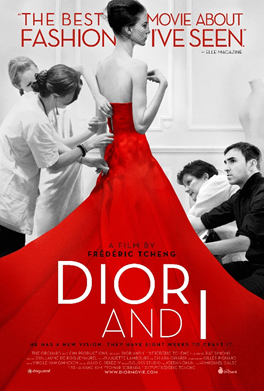

Christian Dior. You’ve probably seen the name somewhere at least once in your life — on a makeup product, perfume, a dress. But who was the man behind the success? The documentary film Dior and I (2014) showcases the legacy of the eponymous man who reinvented the modern dress, creating an outfit that favored the silhouette of the body as opposed to the former boxy style of wartime.

But there’s not an “and I” in the title without reason. In Dior & I, Raf Simons takes on the daunting renowned fashion house as the new Creative Director and has eight weeks to debut his pieces. One problem that first presents itself is Raf Simons’ previous experience at a minimalist fashion brand. However, we begin to learn from Raf himself that he thinks more similarly to Dior than we originally expect. Drawing inspiration from art and sculptures — and of course, Dior’s works — Raf designs pieces that merge extensive beauty with simplicity. Throughout the documentary film, the viewer gets to learn not only about the figureheads, but the entire team — the ones who threaded the clothes, made the design possible, and more.

Dior and I celebrates the beauty of craftsmanship, but it also celebrates those who continue to strive towards an aesthetic that reflects the legacy of a man who revolutionized fashion.

— Alice Xu ’20

Pascal Campion’s artbook is entitled 3000 Moments (2014), a fitting name for his sketches, which depict all sorts of fleeting, everyday snapshots in a deceptively simple style. Campion’s use of color and lighting is gorgeous, drenching his artwork with a movie-camera glow, and his compositions give a lot of focus to the scenery, which include dazzling city lights, serene forests, or cozy interiors. Instead of a strict adherence to realism, he uses breezy, impressionistic swathes of color, to suggest detail, though his use of shadows, dappled light, and water reflections for visual interest are impressive. The people he draws are also charming, with their spindly limbs and simple expressions, as they laugh or relax or fall in love.

Flipping through 3000 Moments is like perusing an idealized photo album, featuring the memories people wish they had, or the candids they wish were caught on camera. Quiet moments of reflection by a beach or a city balcony are sandwiched next to delightful little family interactions, with kids running through the door as autumn leaves blow past or getting into scrapes with the dog. People bike past beautiful sunsets, splash through puddles during a shimmering rainstorm, or curl up in a library with a good book. Each shot is dripping with atmosphere and brimming with life; you can almost hear the sound of a drizzle outside the window or feel the cold bite of a breeze.

Aside from the physical artbook, Campion posts his art on various social media sites under pascalcampion (deviantArt) or pascalcampionart (Facebook, Instagram).

— Sydney Peng ’22

For some reason I left a tab open on James Blake’s “Don’t Miss It” for months. And even once I had finally quit, closed the tab and found new songs to obsess over, I continued to look it up, to play again, and again, and again, until the song was as easy as thought in my mind.

This latest song by Blake, fits with the usual R&B, electronic style found in his previous albums Overgrown and The Colour in Anything from 2013 and 2016 respectively. But there was something about this most recent song that kept drawing me back.

Perhaps it was that haunting, entrancing melody, with the slow, fragmented singing. The only elements to the song are piano chords and intermittent background humming, with Blake’s singing serving as the most complex piece, his voice being drawn out, almost skipping over itself, trying to catch up. It is easy to let the words wash over you so that you cannot even hear their meaning anymore, so that it becomes part of the heart-wrenching tune.

Or perhaps it was how fitting it was the first time I heard it, driving down the 405 near Los Angeles, letting insecurities rattle in my skull as the song lists being able to “avoid the 405,” in James Blake’s haunting voice, alongside other reasons to avoid engaging with the world. The music video contains lyrics being typed out in the notes app on an iphone, as the singer/writer lists all the reasons to avoid trying, or connecting, or “coming to life,” all of this culminating with the idea that “I’d miss it.”

Don’t miss it.

— Kate Kaplan ’22

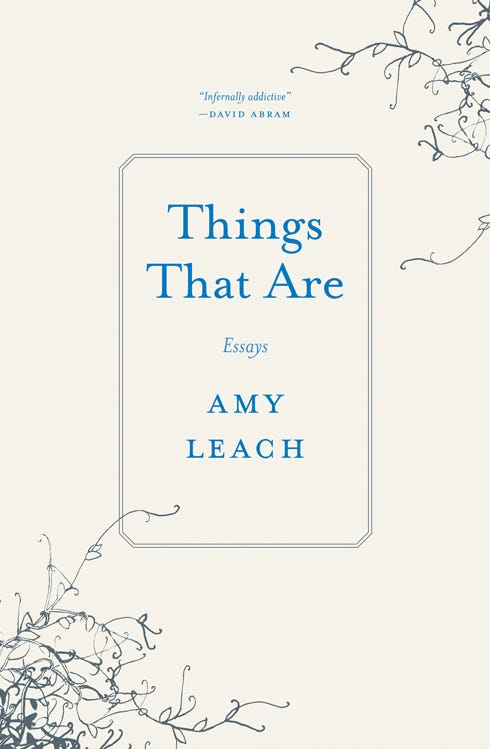

It is hard to classify Things That Are by Amy Leach (2013) as any specific kind of writing, as its pages drift (like a jellyfish, as Leach might say) between poetry, essay, prose, and origin story. Leach’s collected essays, if that is what they must be called, detail a natural world that seems not quite our own, replete with newly-named feelings and invented holy days (Leach includes, for the reader’s orientation in her lovely world, which may yet be our own, a glossary). Her musings on the earth and its wild, whimsical creatures and creations, are playful odes to all that grows and dies.

In a particularly charming piece, “Please Do Not Yell at the Sea Cucumber,” Leach explores the wafting life of a jellyfish, from the depths of the sea to the washed-out shores, and even to the moon. When she finishes contemplating their motion, Leach ponders jellyfish’s sensitivity to light, noting that they emit light, which she believes makes it likely that they can sense it. Then again, she writes, “. . . jellyfish could be like flowers and people, who express more than they know.” In a charming aside, she compares the jellyfish to the sea cucumber, which, when in distress, combusts (hence, the essay’s pleading title). It is Leach’s agile twists and turns, her graceful musings about all things, from the very small to the very large, that make Things That Are such a delight.

I first read Things That Are two summers ago, because one of the blurbs on its back cover is by Eula Biss, another excellent essayist whose work I would recommend to pretty much anyone (if you’re looking for something else, check out Biss’ Notes from No Man’s Land). How lucky I was that Leach’s essays were my first encounter with the kind of imaginative environmental writing that celebrates and eulogizes and discovers our own Earth as a natural world truly full of life.

— Chaya Holch ’22

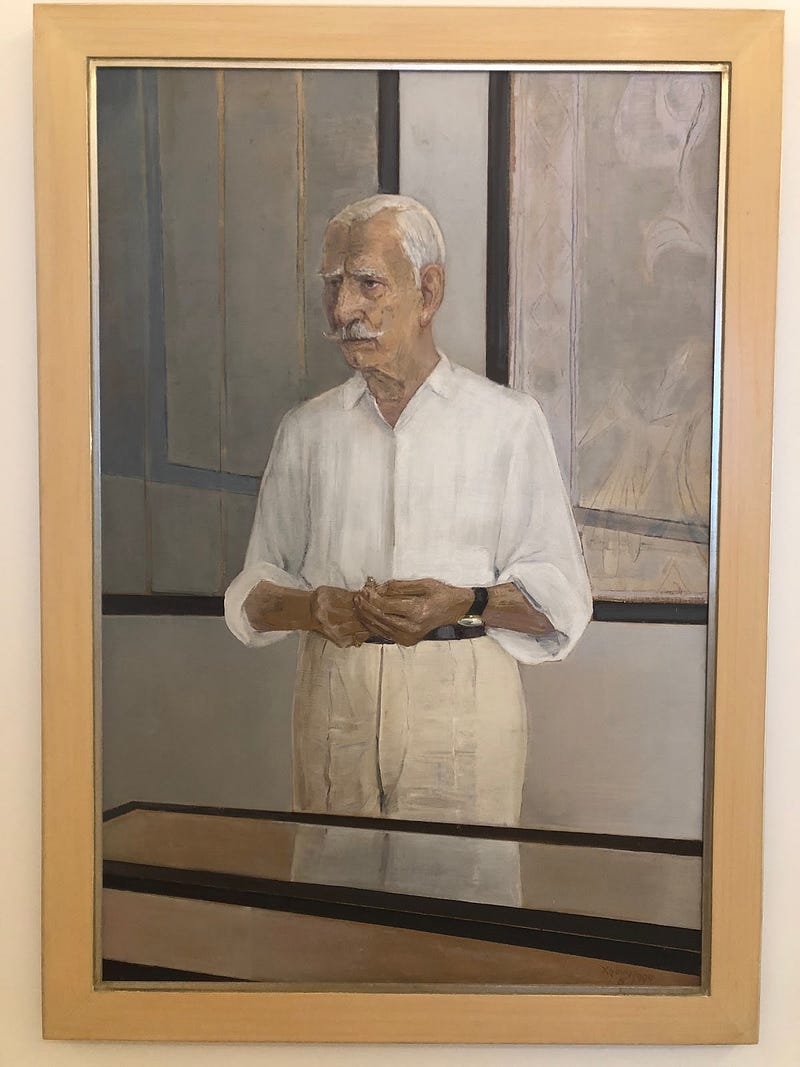

On the walls of the atrium of the Benaki Museum in Athens hang five portraits of Antonis Benakis, founder and namesake of this Greek cultural institution. Remnants of a 2004 exhibition “Near Likeness: Approaches to a Portrait of Antonis Benakis,” they are the first paintings I saw upon entering the museum, standing out on a floor that is predominantly concerned with the sculpture and pottery of the ancient Mediterranean.

Curatorially, the placement of these paintings emphasizes a founding aim to illustrate continuity in Aegean art over the last three millennia. One of them, Chronis Botsoglou’s Portrait of Antonis Benakis, imposes a contemplative Benakis on top of a single white column in the background. With a calmly furrowed brow, the subject appears bemused in the way of a gentleman equal parts aged and monied. The uncertainty within this depiction give way to the absorption of Benakis’ white hair, white shirt, and beige trousers into the marble column, that great image of ancient Greek architectural — and social, and political — achievement. Botsoglou confirms Benakis’ place on the Greek cultural totem.

Some combination of time change and unseasonal humidity kept me from sleep and early the next morning I walked back in the direction of the Benaki. My route was through the National Garden, where I chanced upon a colonnade gleaming in the long sun of the morning. My mind began to wander and it soon stumbled into a Bavarian (not Athenian!) passage of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”:

we stopped in the colonnade,

And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten,

And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.

That was — save for place — my plan for the day and so I read along to a dominant question in the poem: “What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow / Out of this stony rubbish?” What is birthed by our memory of the past? Benaki surely pondered this between his brows in designing his museum.

Eliot saw a desolate portrait, a Waste Land of Western degeneration. But in the shadow of the Parthenon, the Benaki — and its namesake founder — sprouts life and structure from these ancient rocks in the land of the hyacinth. To be sure, the museum chronicles Eliot’s “Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air.” But instead of showing the subsequent “[f]alling towers” of “Jerusalem Athens Alexandria Vienna London,” Benakis’ legacy has spun an optimistic tale of rebirth and growth.

— Isaac Hart ’22

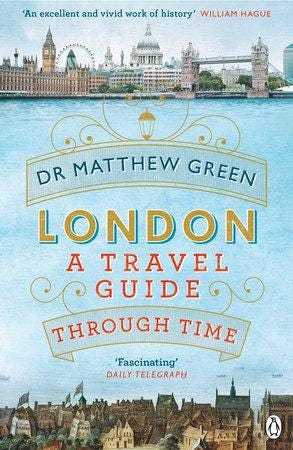

London: A Travel Guide Through Time (2015) by Dr. Matthew Green is a sensory descent into London in four eras: the Elizabethan, medieval, Georgian, and Victorian (and yes, in that unchronological order). His aim is to create an immersive sensory experience of the city, and no gruesome details are spared, from the bloody history of Smithfield — now a meat market, once an execution theater — to the grisly practices of corpse disposal in times of plague. (It turns out that Monty Python was not too far off the historical mark.) But for every sensory revulsion, there is also a sensory delight. We dip, for example, into the caffeine lovers’ paradise of tea, coffee, chocolate of the eighteenth century and savor the intellectual stimulation often served alongside. The jumps back and forth across time without chronological basis can often be jarring, even for the experienced time traveler, but there is something intensely satisfying about reading history almost viscerally, without the distancing mechanism of stuffy academic prose and presumptuous footnotes attempting to dominate the text. Green’s part-history, part-travel-guide, is a fun and informative pleasure-read that puts the “story” back in “history” without taking too many storyteller’s liberties.

— Myrial Holbrook ’19

The Haunting of Hill House isn’t merely about horror. At the root, it’s a family revelation. A modern Netflix adaptation of Shirley Temple’s 1959 novel, this show is an emotional genealogy that details the aftermath of a tragedy, forcing the estranged Crain family together to unravel the mystery of their childhood home. Throughout these ten episodes, this show cinematically flashes from present to past to future to present again, chronologically deceptive, while phantom figures appear and disappear between background frames. There is a charming, atmospheric quality to Hill House itself, from the Romanesque marble statues in various states of repose, to the rusted staircase that curlicues up to a small red door. The history behind this haunted estate — and its ghostly inhabitants — is never fully articulated. What is unsaid is all the more chilling; what is revealed becomes heart wrenching instead.

— Jacqueline He ’22

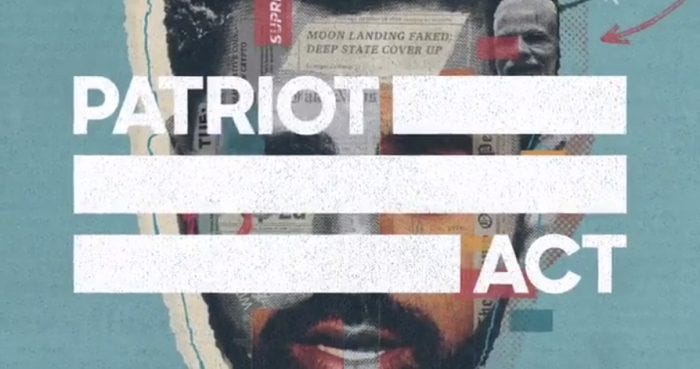

“I’m really brown, I’m really brown,” Hasan Minhaj said to one of Hollywood’s only other brown celebrities, Queer Eye’s Tan France. They were discussing what to wear for his new Netflix show, Patriot Act. “Tan, America is becoming South Asia,” Hasan continued. “ — yoga, meditation, chai tea at Starbucks, us! By the way, Chai tea’s the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard of. You’re saying ‘tea tea.’ It’s like, ‘hey, you want some naan bread?’”

Even off duty, Hasan is just always funny. He combines his humor, social consciousness, and wit in every week’s episode of Patriot Act. He makes the most mundane topics — Affirmative Action, Saudi Arabia, Amazon — captivating. He engages and challenges 5.6% of America’s population — Asians — in conversations that are otherwise only black and white. Most importantly, he makes young people care about things other than the Kardashians.

Hasan’s new show is reminiscent of other satirical news shows like The Daily Show, Last Week Tonight, or Full Frontal, but, speaking as a fan of all four, if I had to pick one, it would hands down be Patriot Act. Hasan’s “brownness” is a fresh and necessary perspective. Plus, the show’s jaw-droppingly beautiful to watch: other than Hasan himself, the visual aids are stunning. In Hasan’s own words, “I wanted to make a show about culture, and politics, and the news…and I wanted to do it surrounded by iPads. I mean, look at this place, it looks like Michael Bay directed a PowerPoint!”

— Priya Vulchi ’22

Over fall break, during some downtime with friends, I watched The Tale of the Princess of Kaguya, a Japanese fantasy animation film produced in 2014 by the legendary Studio Ghibli.

As someone relatively new to anime, I was surprised by deeply the film impacted me emotionally. First, the film’s visuals are exquisite and deeply moving. I was gripped for the full hour and a half merely from watching the lines blur and morph into ever-changing shapes, the water-colors bleed across the page. The wonderment of the visuals beguiled me into a contemplative and naive mood, making every emotion that the story sparked sharper, hit harder.

The film is based on an ancient Japanese folktale dating back to the 10th century. It begins with a bamboo cutter and his wife who discover and adopt a tiny magical baby within a bamboo stalk. She grows unnaturally fast, in spurts, and becomes their beloved daughter, swiftly falling in love with the countryside. However, the father realizes that his daughter is meant to be a royal princess, not a country bumpkin. Uprooted from her rural village and disciplined under a strict headmistress intent on transforming her into a proper princess, drama ensues as she chafes against the formalities of royal life and yearns to run free. Her legendary beauty attracts five suitors who court her hand in marriage, but she rebuffs them.

The plot initially appears to follow a familiar narrative of many western Hollywood productions: a strong-willed heroine who rebels from patriarchal norms and yearns to live life on her own terms (see: Disney’s Moana or Pixar’s Brave). But the plot bucks this narrative with a late-game realization that the princess is from the moon, and to the moon she must return, leaving behind not only her needy suitors, but her beloved parents and friends. She is mandated to return to the moon folk, who appear as immortal faerie-like creatures. The conflict is staged: will she stay on earth, embracing mortal life — full of its miseries and joys, love and despair — or will she live the serene and immortal life of the moon folk. Yet Princess Kaguya’s future does not hinge upon an individual choice as much as magical intervention. She leaves as she comes — magically, inexplicably — leaving you with just the ache in your chest as proof that it wasn’t all a dream.

— Rebecca Ngu ’20

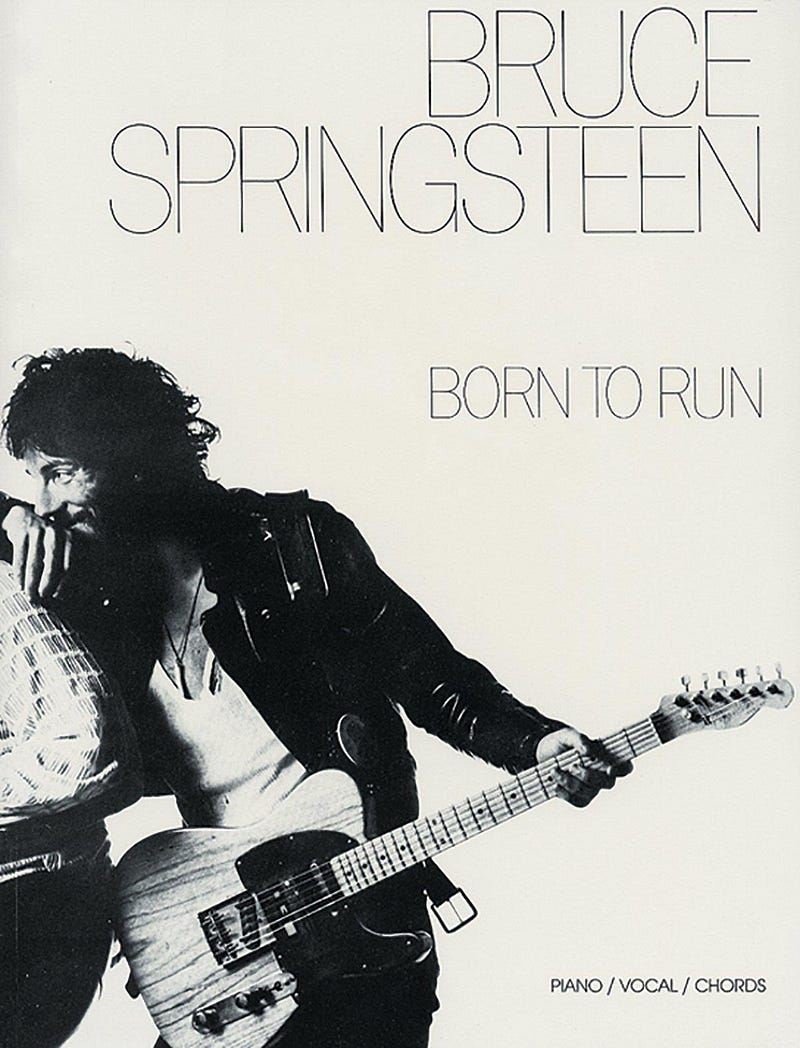

“Tonight all is silence in the world

As we take our stand

Down in Jungleland.”

Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run (1975) has become my hot chocolate on a cold winter day — that timeless comfort that never fails to warm the soul. No, I wasn’t a blue-collar teenager in Monmouth County during the 70s. I wasn’t even close to being born. Yet, Springsteen never fails to resonate; his music is universal. Whether it be the evocative imagery of the vie quotidienne of “Jungleland” or the upbeat anthem, “Born to Run,” capturing the freedom — the will — of his generation, there is always at least a foothold for me to cling to; I feel as though I was there with him.

Sometimes it’s so easy to get caught up in life that you forget to live it. Springsteen’s music is nostalgic, bringing you back to the summers when that’s what it was all about — living. He dealt with the Vietnam War, teen pregnancy, crime, and the struggle to make ends meet on top, but never failed to infuse hope: things will get better. Princeton, while right around the corner from the hearth of Springsteen, couldn’t be further from his reality. Every once and a while I’ll cue up Born to Run, stop studying and fretting, and just live, like they do outside the Orange Bubble.

— Sam Himmelfarb ’22

I spent fall break in my hometown of New York City, feeling like I’d put on a beloved old shoe that suddenly felt too big, threatening to slip off. With my parents at work and my sister at school, I spent a few days wandering aimlessly around my neighborhood, the notoriously not-so-vibrant Upper East Side. With no particular aim, I walked into the Jewish Museum, perhaps to get a whitefish bagel in the basement Russ & Daughters.

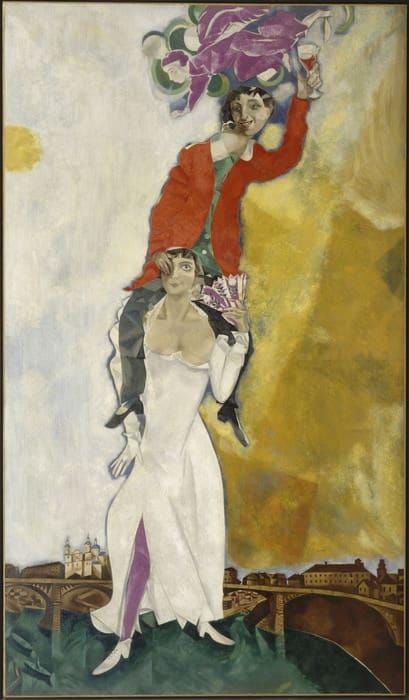

Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918–1922 turned out to be one of the most thought-provoking visual art exhibits I have seen in the past year. Open until January 6th, the exhibit gives a unique lens into one of the cornerstone questions of art history: “How does a society’s political and social change impact its art?”

The curator presents us first with the necessary historical background of the Russian Bolshevik revolution of 1917, contextualizing the conglomeration of artists subsequently showcased. Though varying in style from mystical expressionism to barebones geometrical abstraction, all the artwork roots itself in pushing the envelope of modernity and fighting for an ideological good.

What moved me most, perhaps due to the timeliness of the inspirational message, is the ways in which the giants of 20th century Jewish art stayed grounded in their religion, relentlessly weaving spirituality and tradition into their work regardless of the cost to their perceived validity in Communist circles. Marc Chagall’s Double Portrait with Wine Glass celebrates the beauty of his own Jewish wedding, while El Lissitzky’s illustrations use the plot and images of the Aramaic Passover song “Had Gadya” to craft a subtle narrative on the fruitlessness of cyclical vengeance in the revolution.

— Marie-Rose Sheinerman ’22

Sculpture is, by definition, static, but Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) molds stone into a dynamic state in Apollo and Daphne, displayed at the Galleria Borghese in Rome. Annotating an Ovidian myth, the sculpture depicts Apollo’s lovestruck chase of the maiden Daphne, who prays to her father Peneus, a river god, to “change the body that destroys my life” and save her chastity. Peneus answers her prayer, transforming Daphne into a tree. In Bernini’s sculpture, Daphne’s toenails extend into roots, her arms branch into laurels, and her skin shifts into bark just as Apollo reaches her. Bernini juxtaposes textures — the coarse bark, her smooth skin, the crags of a rock below their feet — suggesting that the pristine, white marble of Daphne’s original body is a sign of purity, now inaccessible in its sheath of bark and leaves. Daphne’s dignity and autonomy are preserved at the frustration of Apollo, as his hands graze rough bark and his thigh is tickled not by human fingers but laurel leaves — his expression does not yet show alarm or realization at Daphne’s transformation.

Bernini’s craft is all the more shocking because his subject matter is Daphne’s near escape from rape. I felt both in awe of the technical mastery in the sculpture and repelled by Daphne’s pained expression, pulled between wonder and empathy for the mythical tragedy underway. Apollo and Daphne represents just one of many Baroque sculptures depicting scenes of assault that were created for and by men, including Bernini’s famous Rape of Proserpina. Should we problematize the Baroque and Renaissance fascination with rape as seduction? Bernini’s artistic mastery overwhelms the urge to historicize or question its content — yet it is all the more pertinent to address the theme of Daphne and Apollo given the power and precision of Bernini’s visual version. Bernini urges the viewer to shudder at the scene at hand and the very voyeurism inherent in its public display — perhaps engaging this discomfort both undermines the male gaze present in the sculpture and serves as a tribute to Bernini’s artistic power.

— Simone Wallk ’21

Praise Satan for the Chilling Adventures of Sabrina! Inspired by the “Sabrina the Teenage Witch” comics from the Archie universe and the subsequent 1996 T.V. series starring Melissa Joan Hart, Netflix’s new twisty take on our favorite headbanded witch is deliciously arch, self-aware, and, of course, wicked. Choice quotes include: “Penny dreadful for your thoughts?”, “You had me at ‘tormenting mortal boys’”, and the glorious “Ugh…succubitches.” Fans of the CW’s Riverdale will recognize Chilling Adventures’ confusion over whether it is a droll comedy, teen drama, or crime thriller. But for a show whose protagonist straddles the line between the human and witch realms, the genre-bending feels right at home.

Chilling Adventures is also unabashedly feminist (as it reminds us every episode). At points, it’s a bit hat on a hat. Feminism is Sabrina’s brand in both her mortal life and her witch life — the show’s central conflict is that Sabrina refuses to sign her freedom over to Satan in exchange for full witch powers because she doesn’t want to be controlled by a man. While this supernatural take on feminism is fresh and interesting, Sabrina’s feminist crusades for her mortal friends feel self-involved (read: Taylor Swift feminism). She speaks over her non-binary friend Susie and African-American friend Roz, while claiming to fight for and empower them. (Sidenote: Lachlan Watson and Jaz Sinclair, as Susie and Roz respectively, are highlights of the series.) But this arrogance is one of Sabrina’s main flaws that we see elsewhere in this series — perhaps her personal development will lead to a change in her activism, a growth arc I think would be important for T.V. to see.

But easily the best part of Chilling Adventures is its witty, honest-to-goodness (or honest-to-evilness?) Satanism. The satanic salutation with which I opened this WWL is said often throughout the series by Sabrina’s Aunt Zelda, who wields a cigarette holder with such style as to rival Audrey Hepburn. Over ten episodes, we meet demons, devils, and The Devil. The show is so meticulous with its Satanism that it has in fact been sued by the real-life Satanic Temple for copyright. How (penny) dreadful!

— Sylvie Thode ‘20

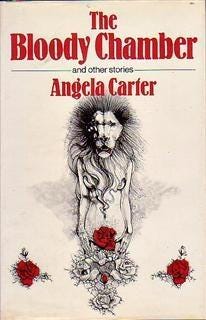

Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories was published in 1979. The collection contains ten reworked fairy tales, many familiar to us from Disney adaptations, particularly Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, Beauty and the Beast, Puss in Boots. Others are based on popular folk tales: Little Red Riding Hood, the Erl-King, variations on werewolf themes. Carter conflates and rewrites aspects of these stories, telling them as dark and sensuous tales. She stays true to the authoritative tone of folklore even as she moves among various narrative voices and personalities. By working with previously constructed and well-known plots, Carter asserts her place within a literary tradition, even as she subverts it. Much of her subversion is related to gender and sexuality. Her tales are notable for exploring the interiority of traditional female characters, and for blurring the line between innocent princess and evil witch, letting characters occupy in-between spaces.

Though many of the tales add sexual elements where they were previously implicit (at most), Carter was adamant that her work was not the sexualization of these primeval tales. She explains that her motive was to “extract the latent content from the traditional stories” (from a 1985 interview). The stories, then, are the relevant fairy tales for our post-Freudian age: Latent sexual content is brought to the fore. Carter shows us that these tales are not antiquated, only antique. And, to indulge the metaphor, Carter has gone thrifting and brought these stately pieces into the fore of modern spaces, giving them new relevance.

Aside from the evocative content of Carter’s stories, the dark, sometimes bloody, always macabre plots are perfect for curling up with hot tea under a warm blanket when proportion of the day that is night is increasing at its fastest rate. This time of year, late autumn, is the temporal setting for eight of the ten stories, which take place in the cold, from fall through midwinter. My personal favorite, “The Erl-King” takes place on “a cold day of late October, when the withered blackberries dangled like their own dour spooks on the discoloured brambles.” She writes that “the stark elders have an anorexic look; there is not much in the autumn wood to make you smile but it is not yet, not quite yet, the saddest time of year.” The story, like many in the collection, is about desire: for love, for sex, for freedom, and the dour spooks of each of those.

— Tess Solomon ’21