What We’re Loving: Back-to-School 2019

Simultaneously dream-like and restless, Ada Limón’s latest collection of poems, The Carrying (2018), feels like an embodiment of summer — a pause in the midst of chaos. From her first poems which grapple with infertility, one of the book’s recurring themes, to later pieces that study death and loss, Limón embarks on an exploration of what it means to feel stalled while the world keeps moving, and to be moving with it, somehow, at the same time. In “The Visitor,” one of the book’s earlier poems, she uses an interaction between the neighborhood cat and dogs to get at her own sort of existential anxiety:

I do what I do best: nothing. I watch the cat

leap into the drainage ditch, dew-wet fur against

the daylilies, and disappear. The dogs go quiet

again, and the mice are safe in their caves, and

I’m here waiting for something to happen to me.

What I love most about Limón’s writing is its humility, and its simultaneous elevation of the mundane. Her poems strike a conversational tone, often seeming more like internal dialogues with the self rather than with a larger audience. Limón takes aspects of daily domestic life, such as weeding or taking a bath or driving to the airport, and turns them into examinations of womanhood, love, and death, proposing that these mundane elements of life are perhaps not mundane at all. Her keen eye for the beauty, the greatness of small things, is perhaps best summed up in the final lines of “The Last Thing,” an ode to the simple observations made in a day, written as if the narrator is speaking to an unknown other:

I know

you don’t always understand,

But let me point to the first

wet drops landing on the stones,

the noise like fingers drumming

the skin. I can’t help it. I will

never get over making everything

such a big deal.

— Shira Moolten ’21

Chia-Chia Lin’s debut novel, The Unpassing (2019), opens with a memory: the narrator, Gavin, recounts the moment his mother played dead in front of him and his sister. It’s the silence that fills this scene, Lin’s remarkable attention to detail as she focuses in on the sunlight glossing on the mother’s hair, the sister’s halting breath, and red red veins, before the scene snaps back into wakefulness. The mother yells at her two children for failing to call the ambulance. Gavin gapes at the immediateness of an undoing, an erasure of events.

This theme of forgetting — or being doomed to remember — is the skeleton of The Unpassing, as is the narrator Gavin’s unique position in the novel. Although most of the vignettes sewn across these pages happen when Gavin is around 10 years-old, the innocence of his narration is at times violated by mature and introspective, adult reflections, where Gavin, in real time, physically is (in the future looking back). In many ways, this novel is a time-warp and as such, the effect of stories as they unfold before Gavin and his family gain the illusion of melancholy, regret, and inevitability.

There is so much depth and detail to this novel that I’m still struggling to put it all together in my mind. In simplest words, The Unpassing is the story of a Taiwanese immigrant family in the 1980s who move to Anchorage, Alaska. According to the narrator’s father, he does this so his family can be “closer to the stars.” Of course, this sweet explanation that Gavin grasps onto as a young boy, and which haunts his view of his own displacement and his father’s (anti)heroism, is far more beautiful than its reality. Dramatically, and yet somehow very silently, the family faces first the death of Gavin’s youngest sister, Ruby, then a spur of other misfortunes: homelessness, poverty, and through it all, the harsh, beautiful, and unforgiving landscape of Alaska. What Chia-Chia Lin does so spectacularly in this novel is peer unflinchingly into the dynamics of an immigrant family; specifically, the ways in which they wield silence, and how their attempts to make it a form of armor merely turn it into a weapon. Ruby’s death is never explicitly revealed to the Natty, the youngest child, and as a result he grows up angry, traumatized, and unable to properly communicate. The father spends his days listless, staring at stars, and telling Gavin nothing but to eat more and grow. The mother does nothing but reminisce about Taiwan, and nobody in the family truly communicates with one another. The mother barely knows where her children ever are.

I picked up The Unpassing after trying (and failing) to read a novel with a different Asian American protagonist, one that I felt was not contrived and annoying and baseless. In here, there is no romanticization or tokenism. Each character feels real and uniquely American as much as they feel uniquely foreign. Gavin, in his own innocence and youth, in the midst of his parents’ failing marriage and his sister’s sexual escapades, fails to fall into any categories of superficial representation. He is quite simply a 10-year old boy perched at the mercy of the Alaskan wilderness, constantly on the verge of death, and very very much alive.

— Noel Peng ’22

If, like me, you’ve been obsessed with HBO’s Euphoria, T.V.’s newest contribution to the timeless “sex, drugs, rock ’n roll” genre, this song has probably been the heartbeat of your summer. Snippets of “All for Us,” written and performed by the British producer Labrinth, run throughout the series as playful transitions. But when the full song plays at the final moment of the first season and the protagonist Rue, who is played by Zendaya, begins to sing its verses, the fourth wall explodes and what was once a show becomes a VMAs performance to rival the legends (hi, Gaga 2009 and Britney 2001!). There’s a marching band. There’s Ryan Heffington choreo. There’s a rapping gospel choir. There’s Donni Davy’s stunning makeup. And then there’s Zendaya, in peak form. Handled in hands less deft than director Sam Levinson’s, it would be overkill. But this is Euphoria, where teenage addicts cry tears of glitter and the world quite literally revolves around two friends in love. It works.

Although the staging of “All for Us” is a crucial part of the song’s power, I’m haunted most of all by Labrinth’s gorgeous lyrics. The opening call-and-response between him and Zendaya is fantastic, but the song’s bridge is the real gut-punch. Much ink has been spilled already about the final words (“I hope one of you comes back / to remind me of who I was / before I go disappear / into that good night”) and whether or not they mean that Rue has relapsed. The attention is well-deserved: those are some of the most affecting and brutal lyrics I’ve ever heard. But I can’t help fixating on the preceding lines:

Guess you figured my two times two

Always equates to one

Dreamers are selfish

When it all comes down to it

This is Labrinth’s lyrical brilliance at its best. The lines are ostensibly simple, the appearance of multiplication tables almost comedic. But they give voice to a cruel phenomenon: dreams can be weapons, depending on whose they are. Who among us hasn’t been the collateral of someone else’s dream?

And who can say they haven’t been a selfish dreamer?

— Sylvie Thode ’20

I’ve always harbored a deep-rooted appreciation for the heartiness and warmth of old Japanese structures, but after spending the summer abroad in Japan, my love for traditional Japanese aesthetics is stronger than ever. I still remember the feeling of uneven, weathered grain of exposed wood and the grassy woodish scent of fresh bamboo tatami mats. Upon returning to America, I yearned to experience once more the sensation of existing within the tender confines of a traditional Japanese space, and after a bit of poking around quickly discovered In Praise of Shadows by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki.

In a brief yet exquisite meditation on the allure of traditional Japanese aesthetics, novelist Jun’ichirō Tanizaki explores the beauty in darkness and shadows through a sweeping analysis of traditional Japanese architecture and art. Tanizaki praises the softness and depth created by candlelight and paper lanterns, and speaks of the irreplaceable glamour of dark patina. Throughout the essay Tanizaki pits the aesthetic preferences of the West up against that of the East, arguing that while the West strives to eliminate any and all traces of shadow and darkness within the home, the Japanese relish and even thrive in the shadows. He laments over what Japan could have been if the minds and hearts of East Asia had never been polluted by the scientific inventions of the West.

Perhaps his most fascinating argument takes the antagonism of light versus shadow to the subject of race. About halfway through his meditation, Tanizaki begins using traditional Japanese performing arts, including the Kabuki and Nō theatres, as his evidence. He argues that shadowy stage lighting caused by candlelight actually makes the actors on-stage appear more beautiful than when modern spotlights are used to illuminate the performance, as the warmth of the candlelight pairs well with the yellow undertones of Japanese skin. Tanizaki asserts that while these undertones usually muddy the skin of the Japanese in contrast to the clear, light skin of the Westerner, within the traditional environment of Nō theatre, the patina of Japanese skin becomes vibrant and beautiful.

As an Asian-American myself, I found Tanizaki’s race-argument the most compelling of his points. In America, although I’ve always experienced the undesirable side-effects of my yellow-tinged skin, I rarely hear anyone talk about the problems associated with the color yellow; the racial conversation is often limited to white versus black. While racism against black people is the most extreme and historical case of racial discrimination in America, it does not mean that all the gradients of color which lie between the two opposite points of the color spectrum are exempt from the chains of racism. When I first began reading Tanizaki’s meditation, I thought that I’d leave with a few, new provoking ideas regarding Japanese aesthetics; and while this is certainly true, I ultimately adopted a fresh perspective regarding the color of my skin in the greater context of a white world.

— Cameron Lee ’22

Before travelling to Aix-en-Provence, I did not hold very much appreciation for contemporary art, preferring instead the classic thick brush strokes and familiar beautiful imagery of the impressionists and post-impressionists. And for several weeks, even amidst the diverse French art scene, I engaged mostly with the works of Paul Cezanne, Picasso, and Monet, whose paintings were available for viewing in several museums and art installations around the city.

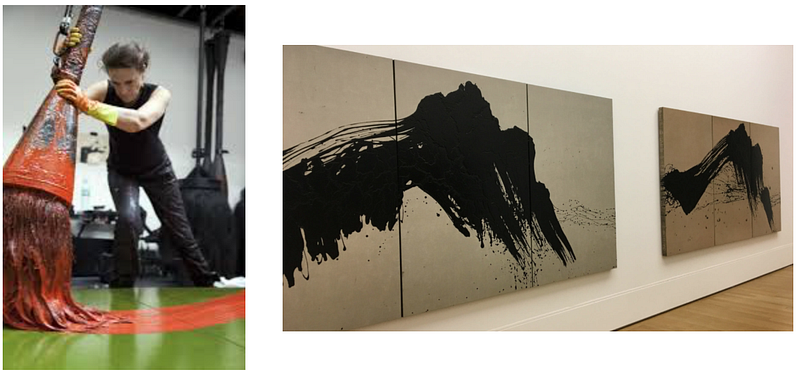

Then, almost by chance, a friend introduced me to Fabienne Verdier’s fascinating art and unique style, which was being showcased at a few community centers. At one museum, I was able to view and interact with one of her giant brushes, which was suspended from the ceiling with a system of lifts and pulleys that allowed the user to move it across a large canvas spread along the floor. The same tool was used to paint her representation of the mountains surrounding Aix-en-Provence. This brush was just one among her many atypical art tools that she used to illustrate her larger than life artistic imagination. For example, at another installation, I was able to watch a documentary about a joint project Verdier engaged in with music students at Juilliard; as they played, she, using different sized brushes, painted jagged black lines and swirls that, to her, represented each note, rhythm, and staccato beat. Occasionally, she followed scribbled patterns she had transcribed beforehand in pencil.

Faced with such a dynamic expression of creativity that, although foreign, was incredibly appealing to me, I couldn’t help but develop a newfound respect for contemporary artists. And sometimes, as I think back to my one afternoon spent playing with Verdier’s man-sized brush, I can’t help but wonder what it would feel like to have that much artistic ingenuity coursing through me.

— Nancy Diallo ’22

Two years ago, Washington D.C. was ablaze with Kusama fever. A groundbreaking survey of the Japanese artist’s work entitled Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors had just opened at the Hirshhorn Museum, and everyone — and I mean everyone — had to see it. Lines for the exhibit circled the entire block, twice. Timed tickets to enter the six featured Infinity Mirror Rooms sold out in seconds. The Infinity Mirror Rooms were small chambers covered floor-to-ceiling with mirrors and littered with objects of intriguing colors, textures, and shapes: sparkling LEDs, giant polka-dotted inflatables, miniature pumpkins. Ripe for selfie-taking, these environments produced thousands of sharable, likeable images that flooded social media feeds for months. Yet I was underwhelmed. I got only seconds to stare into the vast field of Kusama’s signature orange and black glass pumpkins, let alone take a picture. Was this all there was, backdrops for an instantly viral photo shoot?

I couldn’t help but be reminded of Infinity Mirrors when I stepped into Menesunda Reloaded, a reinstallation of Marta Minujin’s original La Menesunda at the New Museum in New York. In 1965, the Argentinian artist developed a labyrinth of eleven spaces at the Center for Visual Arts of the Instituto Torcuato di Tella in Buenos Aires. Widely considered a pioneer of Latin American conceptual art, Minujin worked in film, performance, installations, and more, often commenting on mass media and celebrity culture. The work’s title is slang for a confusing situation — and indeed, it was. After entering through a human-shaped doorway, I was confronted with a blinking tangle of neon lights. I saw myself on a row of security cameras and walked into a couple lying in bed. A stylist asked if I wanted one of my nails painted. I stumbled through what seemed like giant sausages hanging from the ceiling. I crawled through a narrow corridor covered with bits of yellow sponge. I opened a refrigerator. My time was brief, but the journey was expansive, ever-changing, unpredictable. Each entrance offered up something new. Sure, people marched through with iPhones in hand, snapping selfies at every possible opportunity. But I’m sure they couldn’t capture their bewilderment, wonderment, and even pure joy, in a photograph.

— Katie Tam ’21

Are you bummed out that HBO did not air a new season of its hit-show Insecure this summer? Then, if you have not already, check out HBO’s latest series A Black Lady Sketch Show, which premiered on August 2nd, 2019. Created by Robin Thede, who was the first Black woman to become the head writer for the late-night talk show The Nightly Show with Larry Wilmore, A Black Lady Sketch Show includes a host of comedic sketches, organized around an apocalyptic event that has left four Black women the only human beings on Earth. And these four women — played by comedians and writers Robin Thede, Quinta Brunson, Ashley Nicole Black, and Gabrielle Dennis — inhabit a range of other characters in sketches that feature other high-profile Black actresses like Aja Naomi King, Laverne Cox, Angela Bassett, Issa Rae, Tia Mowry, and Kelly Rowland. From skits about ashiness, natural hair, and unattainable beauty standards to a riff of William Shakespeare’s most famous play Romeo and Juliet (sneak peek: the warring fandoms are #bardigang and #barbz), A Black Lady Sketch Show is refreshing, electric, and subversive, playing on age-old racialized tropes, satirizing common stereotypes, and offering cogent reflections on dilemmas that women of our generation face. But perhaps what I love most about the show is its opening credits: Megan Thee Stallion’s “Hot Girl” creates the milieu of a hot girl summer as we see black puppets live their lives by their own eccentric terms.

— Rasheeda Saka ’20

Patricio Betteo is a Mexican artist with a refreshing blocky style that makes use of interesting angles, lighting, and color palettes to convey a sense of vibrancy. Crunchy textures mesh with stark shapes and harsh shading and papery brush strokes that give a collage-like effect. The amount of lineart can jump from impressionistic skyline paintings to incredibly-detailed scribbly grid-paper cityscapes, but both have a similar frenetic energy that extends to his depictions of people and wildlife, with their exaggerated features and elongated, angular limbs.

Patricio Betteo has a deviantART account (betteo), an Instagram (patricio.betteo), and a Blogspot (betteo).

— Sydney Peng ’22

Flannery O’Connor’s short story “The Geranium” follows Dudley, a man from the country forced to live with his daughter in New York in his old age. His daughter keeps him not out of love but “damn duty.” Dudley is unable to adjust to the city. The first paragraph says that “his throat was drawn taut.” He sits by the window all day trying to occupy himself. Every morning, he watches someone put geraniums in the opposite window. On the day the story takes place, the flowers are late. The geraniums are the only stable occurrence in Dudley’s new world, and their absence unsettles him.

The story’s most dazzling feature is its piercing portrayal of race. Dudley fondly remembers fishing and hunting with Rabie, his right-hand man back home. Though he has some affection for Rabie, Dudley sees black people as subordinates. When he sees a black man in his daughter’s building, he is surprised that “the kind of people that would live thick in a building could afford servants.” Dudley wonders if the man can accompany him on a hunting trip, just as Rabie did. Dudley’s daughter explains that the man is not a neighbour’s servant but a neighbour. Dudley explodes, “You ain’t been raised to live tight with niggers that think they’re just as good as you … !”

Racial tensions are heightened when Dudley falls down the stairs and the black neighbour comes to his aid. This powerful scene captures Dudley’s world turning upside down. He can’t believe that the man is openly amused at his fall and that he talks to Dudley as an equal. Dudley is mortified at being dependent on a black man.

As Dudley returns to his apartment, O’Connor brings back the ache she established in the beginning, writing, “The pain in his throat was all over his face now, leaking out his eyes.” Dudley is now desperate to see the geraniums. Instead, a stranger in the window watches him cry. Dudley demands to know where the geraniums are. The flowerpot has fallen and is “at the bottom of the alley with its roots in the air.” The flowers are symbolic of Dudley’s old life and ideas. He resolves to bring the geraniums up, but seeing the stairs reminds him of his shame. He can’t save the flowerpot any more than he can go back to his previous life.

One of O’Connor’s greatest talents is her ability to weave in and out of scenes. This story contains the best transition I’ve ever read — “He could er knocked ’em out like clay pigeons. Bang! A squeak on the staircase made him wheel around — his arms still holding the invisible gun.” The narrative flows so beautifully from Dudley reminiscing about a hunting trip to being startled on the staircase that the reader is hardly aware of the transition. The language and imagery are delightful — “People boiled out of trains and up steps and over into the streets.” ‘The Geranium,’ available for free on Farrar, Straus and Giroux’s website, is an excellent story for those new to O’Connor and devoted readers alike.

— Ashira Shirali ’22

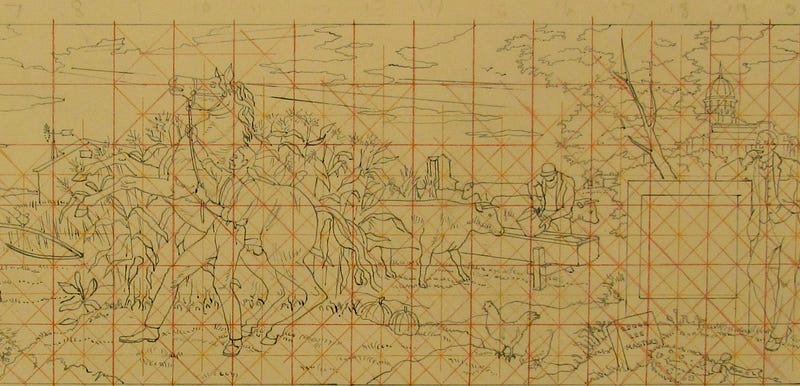

A few weeks ago, I went to the University of Georgia’s Museum of Art with a close friend of mine who had come to visit me over the weekend. Despite having lived fifteen minutes away from the university for almost six years, I had somehow never visited the art museum before, and I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. I’d been a bit spoiled in terms of art museums over the past year (having had access to the Met and the Princeton Art Museum — the sorts of places whose walls are lined with Picassos and Monets), and I was a bit skeptical about the sort of experience a much smaller and much less well-connected museum could provide.

As it turns out, I had nothing at all to worry about. We wandered around the pristine exhibits, marveling at everything from massive paintings of saints to delicately rendered paintings of fruit platters to ornate pieces of furniture to silverware that probably belonged to Paul Revere. One of the exhibits featured sketches and studies artists had made in preparing to create a mural; it was fascinating to see what changes had been made between the preliminary sketch and the final product and to read about why some of the murals were ultimately destroyed or left unfinished. Another, called “Color, Form, and Light,” featured art that invited visual interaction: a giant piece of curved red glass that you could walk around and look through; a piece made of hanging threads that revealed a white three-dimensional pyramid inside as you turned your head about it; and a large, whirring contraption filled with moving colored discs that constantly overlapped to form new shapes and colors. Every piece invited delight, curiosity, and reflection.

As expected, I didn’t see any Picassos or Monets that day. Still, there was nothing at all wanting from my experience of the Georgia Museum of Art. Any collection of art, regardless of scale or renown, can move us. I’m looking forward to visiting the museum again the next time I visit home.

— Mina Yu ’22

As August does a slow wind down to crispy leaves and too many cider doughnuts, I’ve decided I love self-invention, self-love, care and acceptance. It sounds like a lofty concept. These days, self-care means meticulously documenting your social media fast on social media and buying just the right candle to achieve your most elevated self. That’s not what I mean. This is not an arrogant ode to the illusion of perfection; rather, a gentle reminder to just keep swimming. See actionable steps below:

1) Transition from Hot Girl Summer to Hot Nerd Fall, courtesy of Megan Thee Stallion. This means streaming her mixtape, “Fever,” actually going to your professors’ office hours, and choosing intellectual pursuits you actually enjoy!

2) Go to the gym. We are not trying to be Instagram models here; we just want to not be winded when the elevator is broken and we have to take five flights of stairs.

3) Take breaks: realizing that rest is productive and even if it isn’t, you deserve it.

4) Listen to podcasts: Currently: “Black Girl Bravado.”

5) Be more patient with myself and look for moments of joy.

What we’re loving this season is ourselves — all the uncomfortable stages of growth, the good, the bad. In a world that seems ever more cartoonishly chaotic, it is worth your time to be more gentle with yourself and the people around you. These things are not linear; occasionally you will find yourself eating Oreos at 1 in the morning or scrolling mindlessly when you really, really should be working on an essay. But the pursuit of a better self is not about being flawless all the time. Rather, it’s about enjoying the journey there

— Kat Powell ’20