What We Loved: 2010s Arts in Review

She is girl. She is gravel. She is grabbed.

Before A Cruelty Special to Our Species, I flew through books of poems, pausing only to think for a moment and then carry on. This book stopped me in my tracks, and “Ordinary Misfortunes [“She is girl. She is gravel”]” was among the poems that threw gravel into my gears and brought everything to a grinding stop.

I haven’t ever needed time away from a book before. With this one, I stopped every two poems to just sit and be in agony. This was not because the poems employed language designed to provoke angst or because Yoon sat behind her notebook or typewriter dreaming up ways to make readers suffer, but because the terror and gravity of the experiences of the wianbu are conveyed to us, largely, through their own voices — the girls and young women whose tongues are not barbed but through whose directness we are made excruciatingly aware of the depth and permanence of their suffering. Between their testimonies, Yoon yanks us back to the modern day, where the girls who died and have no voice are lost to history (“history will skip her like stone over water” [“Ordinary Misfortunes”]) and the U.S. laughs at the image of a Korean face blown up on a movie screen (“freedom always prevails / which is why we get to see / two Americans / incinerate a Korean face / on Christmas” [“Hello Miss Pretty Bitch”]). Within each “modern” poem, her mind cannot help but skip back to what Korea experienced, what the people lost in wartime, and rings again and again with the evidence of an inherited trauma, a generational suffering, a han (한).

Early this past December, Emily Yoon visited Princeton, and I was lucky enough to hear her read from A Cruelty Special to Our Species. Her demeanor was composed and frank and lacked pretension. At times as she read, though perhaps it was merely my imagination, her eyes seemed to fill up with tears.

— Mina Yu ’22

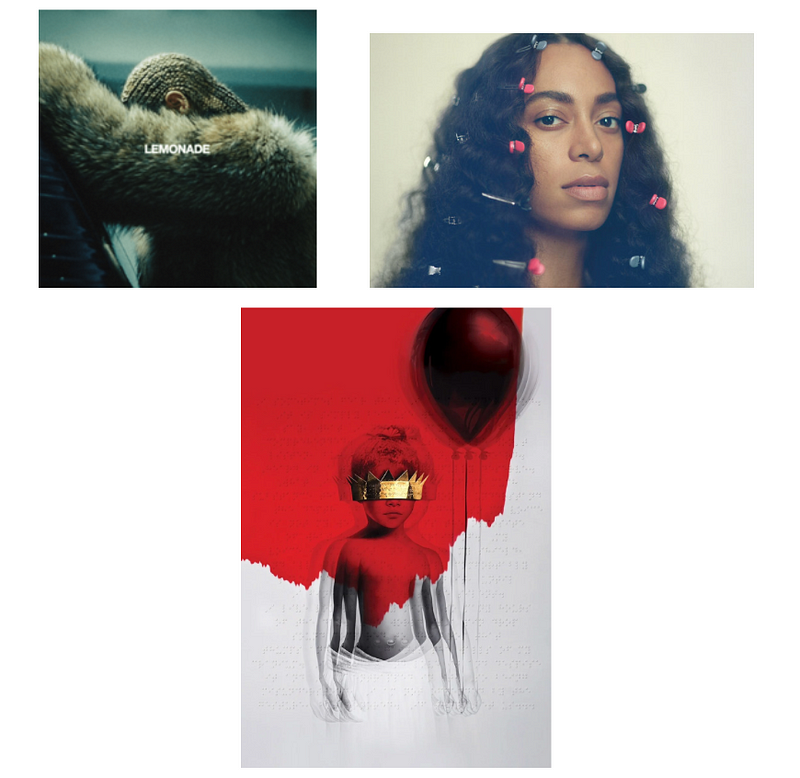

Beyoncé and Rihanna have covered their faces; Solange is open to the camera.

One begins with falling, one with fluttering, one with taste. 2016 was a year of revolution, for me and my friends. I graduated high school, packed my bags and boxes, and moved to central New Jersey. It was, literally and figuratively, very lonely — I moved in by myself and had no friends from high school matriculate with me at Princeton. The Knowles sisters told me I could be weary and lonely, angry even. Ms. Fenty taught me I could stand on my own.

A Seat at the Table, Lemonade, and ANTI. They’re impossible to rank; they have been the soundtrack of my entire time at in college. Most powerfully, they cover ground that Black women, apparently, have no access to: the realm of emotion. When you are told you are one-dimensional, invisible to those who don’t care to look closely, it is powerful to feel affirmed in all the depths of humanity. These three albums cover every mood on the planet

Melancholy? “Cranes in the Sky.”

Pissed? “Don’’t Hurt Yourself.”

Staring at yourself in the mirror, feeling beautiful and powerful? “Needed Me.”

Each album is a different sonic journey for me — A Seat at the Table is written to Black people and so marks the humor, the vibrancy, and the hope we have even when mired in bitterness over what being Black means in a place like this, somewhere that often feels like a hopeless land (see: “Interlude: Dad Was Mad” and “Mad,” tracks five and six.) ANTI fills you with love of the self, almost like cockiness but more like unassailable confidence. It is a gift to be assured that you are whole and human, “good on your own.” (See: “Needed Me.”) Apparently, it is also Rihanna’s last musical gift to the plebs, considering she (infamously) hasn’t released a project since then.

Lemonade is very personal and genre-bending, considering it deals with Beyoncé’s experience with a philandering husband. It is a portrait of someone in pain, a person who is bitter and hurt. It is accompanied by a magnificent visual album, which takes inspiration from famous Black woman artists such as Julie Dash. By the end, Beyoncé’s voice is soaring and she is standing in the bright light of her love again — “How I’ve missed you, my love,” she murmurs. (See: “All Night.”) That fall in Princeton, who was I missing? A lover or my love for myself?

In Senegalese women’s literature, there is a concept called sani baat — throwing the voice. “The act of throwing one’s voice can create an epistemic violence to discourse that will create a space for hitherto unheard voices.” This is art that is personal and Diasporic. From Houston and Barbados three voices have joined, giving us rhythm and blues, country, hip hop, dancehall. To me, it speaks to Black women in different moments and places of life (if you turn on “Cranes in the Sky” in a room full of us, suddenly everyone is a soprano!) Here we are, seen and heard.

— Kat Powell ’20

Out of a box spewing clouds of liquid nitrogen in the Institute for Conservation Research in the San Diego Zoo, a scientist pulls out a little plastic vial. Inside the vial contains all that remains of the extinct Po’ouli bird: a few cells. Afraid to damage the cell culture, she slides the sacred vials back into the tank. Observing this scene, one can’t help but resonate with the author’s sense of poignant concern: is biodiversity’s hope only stored in “pools of liquid nitrogen?”

After finishing the last chapter of the book The Sixth Extinction (2014) by Elizabeth Kolbert, I couldn’t help but contemplate the environmental implications overseeing humanity’s fate. The title of this chapter, “The Thing With Feathers,” is an allusion to Emily’s Dickinson’s poem “Hope is The Thing With Feathers.” As a basis for her chapter, the extended metaphor of a bird serves to be a symbol of hope of overcoming the threat of the “Sixth Extinction.” Up to the final chapter, Kolbert reminds the reader of the insidious consequences humans are inflicting upon themselves amid the Sixth Extinction. Moreover, she emphasizes that the hope of thwarting fate is not merely having concern but rather taking action.

What makes the book so compelling was the eye-opening paradox that Kolbert’s argument serves to suggest: namely, that the fate of humans, whether the demise or continuity, lies largely in the hands of humans themselves, as humans could be victims of their destruction. Galvanized by Kolbert’s prose, I couldn’t help but contemplate this ironic truth overseeing humanity’s fate. Indeed, our future progress seems promising. From artificial intelligence to genetic engineering, humanity has pushed beyond the limits of the tangible world. However, Kolbert’s novel repudiated my former belief that human technological progress always held a positive connotation for society’s standard of living.

The significance of the book cannot be overlooked, as its discussion applies to all humanity and modernity. In the end, the author invokes multiple calls to action to express her urgent concern for the Sixth Extinction. Whereas the previous chapters served as a scope for the Sixth Extinction in history, the last chapter emphasizes the implications of Homo sapiens (rather than other species) on the Sixth Extinction. Focusing on the human race, Kolbert establishes the dichotomy that humans are fundamentally different from other species because of mankind’s capacity to communicate and escape extinction. The end of the chapter compels the reader to speculate upon what the future holds for humanity, what evolutionary pathway concerns mankind’s fate.

Awakened by Kolbert’s concerned tone of the equivocal present circumstances, I also gained a sense of optimism. While Kolbert’s novel emphasizes how humans are in the middle of an extinction event they are compounding, The Sixth Extinction also suggests that the hope of the future also lies in humanity itself. The striking difference between human nature and other species cannot be overlooked.

Perhaps, it is this paradoxical distinction that invokes a sense of optimism: while humans are arguably the most dangerous species, humans also possess qualities of restlessness, creativity, and communication to avert evolution. These qualities also tie back to the significance of the final chapter: hope, with which Kolbert speculates upon endless possibilities of human exploration to survive the Sixth Extinction.

— Colton Wang ’23

I stumbled upon The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories (2012) in my middle school’s library and checked it out multiple times to try and finish it, which was quite a task, given that it clocked in at 1152 pages. I never ended up completing it, especially since I kept branching out to read the other stories by the featured authors, but I still appreciate it for introducing me to its little niche, involving mysterious telegram signals about killer fog, a hidden village of disappearing cats, giant roving cities of people-chains, and a lake that drowns the guilty from a spilled water glass. The surreal atmosphere, extremely specific and bizarre subject matter, and ambiguous situations and interpretations made for a fascinating rabbit hole to delve into — from this starting point, I found China Mieville’s Bas Lag Cycle, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast, Jeff VanderMeer’s City of Saints and Angels, and Haruki Murakami’s After Dark. It also gave me an appreciation for short stories and novellas.

— Sydney Peng ’22

The political decade through which we just lived was, to put it lightly, turbulent, and no TV show captures the essence of that turbulence better than Veep. With quick-witted dark comedy and some of the most despicable characters on television, Veep gives watchers a peek behind the curtain of the political stage. Julia Louis-Dreyfus shines as the vindictive Vice-President of the United States, Selina Meyers, easily satirizing the petty drama of modern politics (and picking up six consecutive Emmy awards in the process). Yet, despite Selina’s heartlessness, Dreyfus finds a way to craft a vulnerable character who the audience roots for in even her lowest moments.

In its seventh and final season, Veep brought humor and perspective to the 2019 political landscape. I started Veep just a few years ago and binge-watched the first few seasons in order to catch up and watch the final seasons in real time with my parents. Although almost every character in Veep is power-hungry and seems to have selfish intent, this show has given me hope for the political future of our country, and faith in (as Veep portrays it) the wildly incompetent people running it.

— Chloe Satenberg ’23

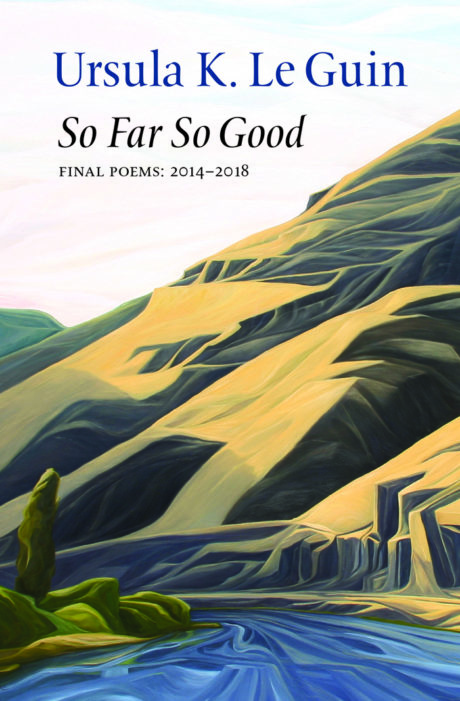

Ursula K. Le Guin, literary giant of speculative fiction, science fiction, and fantasy, passed away on January 22nd, 2018, at the age of 88. Only a week before, she had submitted her final draft for So Far So Good, a poetry collection including many of the last works she would ever write — her thoughts and reflections up to the very edge of her existence.

Le Guin’s Earthsea series had been incredibly important to me when I was about 14 years old, especially its third installment, The Farthest Shore (1972). These were works of fantasy for young people, but they struck me as what fiction “should” be: reverent for life and words, lyrical on the level of prose, imbued with a progressive and sympathetic view, with a highly detailed, developed mythology as its backbone. I was amazed at her ability to make a story that dealt in magic inspire awe. She had she same ability with sci-fi, gaining her fame for works such as The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) and The Lathe of Heaven (1971).

Decades later, in So Far So Good, Le Guin still demonstrates the same reverence. Many of her favorite themes are apparent throughout the collection: forces of nature, animals, Biblical mythology, allusions to science. But Le Guin shines when she meditates on the processes of living and aging, as she does in this poem, from the section entitled “In the Ninth Decade”:

“Ancestry”

I am such a long way from my ancestors now

in my extreme old age that I feel more one of them

than their descendant. Time comes round

in a bodily way I do not understand. Age undoes itself

and plays the Ouroboros. I the only daughter

have always been one of the tiny grandmothers,

laughing at everything, uncomprehending,

incomprehensible.

Le Guin is frank about inertia, longing, anger, and despair. But her short, measured, sometimes lyrical poems, though faintly sad, are strangely comforting. She confronts her own mortality with grace, always aware of the mystery of existence, and perceptive to death as both a “black hole” and an “open door.” The title of her final poem, “On the Western Shore,” alludes to The Farthest Shore of her Earthsea series, in which her protagonists descend into the land of the dead to deny the possibility of cheating death; the poem itself speaks to a delicate knowing, as she confronts the evening, the sea, and sleep. Even at the extremity of life, she possessed, even lived, the fullness of her philosophy, revering the natural cycle of things.

Le Guin remains one of my favorite authors. A small note on a bookplate I received from her in high school serves as a personal inspiration. She has taught me what is important and good about fiction — that even “low” genres have the capacity to touch, in the words of Margaret Atwood, “the immense what is.” And that it is not only possible, but important to touch “the immense what is” in a world that makes that increasingly difficult. This collection, among her final words, offers small reminders of just that.

— Julia Walton ’21