What We’re Loving: Summer 2019 Edition

Friday Black (2018) is an eerie, funny collection of thirteen short stories. Besides the inversion of America’s most gross display of capitalism run rampant, the number of stories might be a nod to the schema of the book, odd and unlucky and conjuring images of gore. It is Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s first book; he comes from Spring Valley, New York.

The most striking thing about the collection are the undertones, overtones, and middle tones of violence. In the first story, “The Finkelstein 5,” a white man beheads five black children with a chainsaw to protect his two kids. After he is acquitted, black vigilantes commence a killing spree of their own in retribution for his crimes. In “Light Spitter,” an unhinged boy kills a girl at his college, then trails her around in the afterlife trying to prevent similar bloodshed from happening again. And in the last story, “Through the Flash,” residents stuck in a time loop after a nuclear catastrophe kill each other to interrupt the monotony of it all.

Friday Black is speculative, Afro-futurist, and quick-moving. The stories are disturbing because they are so contemporary and don’t flinch away from the question of violence — how commonplace it is, how it seems to make sense to us, and how it might be useful. Adjei-Brenyah seems to question the productivity of rage: is there anything noble about vigilantism, or is it as empty as the act it is in response to? Is there any violence against the black body that is so gruesome it will finally motivate people to justice? There aren’t any very neat answers; frequently, the stories end on an abrupt and bleak note. “Through the Flash” suggests that we may have gone so far in our pursuit of technological advancement, national security, and social order that we obliterate ourselves and all that is beautiful about us — the irregularity and asymmetry of imperfect nature. So it ends:

“Even the apocalypse isn’t the end. That, you could only know when you’re standing before a light so bright it obliterates you. And if you are alone, posed like a dancer, when it comes, you feel silly and scared. And if you are with your family, or anyone at all, when it comes, you feel silly and scared, but at least not alone.”

— Katherine Powell ’20

The sun’s been intense, yes, and so has my family time this summer. A wide-eyed, black-coated, lanky, drooling puppy joined our family last month. His name is Zuko. My dog, Obi, hates Zuko. A very energetic, constantly philosophizing, 19-year-old came home from college, too. Her name is Winona. Acquaintance, turned basically sister. When Zuko visited (he’s my brother’s), Obi waddled over to Zuko, lifted his leg, and peed in his face. Enemies. When Winona came to visit this summer, she didn’t knock, just walked inside; the next day, I did the same at her place. On forms, I sometimes put “Winona” under “Your Name.”

Later, a smaller-than-I-thought-humanly-possible baby was born on Father’s Day, making my cousin, well, a father. Holding him was transcendent; tiny heartbeat, tiny nails. “Did you get a tattoo?” my cousin asked as he monitored my baby-holding; I nodded, realizing, wow, I must not have seen him since Grandpa died. It’s my jellyfish Grandpa tattoo.

Next, a curly haired, always grinning, shark-tooth-wearing 21-year-old came home. His name is Ethan. He’s my big brother, and when he sat down at our kitchen table I realized that we haven’t had a family dinner in 5 years. The hours I spent wedged between Obi and Zuko yelling, “You both are family! Come on, love each other!” then with the philosopher, and later with the curly-haired grinner — I understood how this summer is both weird and wonderful, and how intense the sun feels.

— Priya Vulchi ’22

In many ways, Never Let Me Go (2005) by Kazuo Ishiguro is a rather typical example of the dystopian genre, with Madame, the mastermind of society; Kathy, Tommy, and Ruth, the tight group of childhood friends; and the organ donor system, a manifestation of human greed that jeopardizes the legitimacy of human morality itself. Unlike its predecessors, however, “Never Let Me Go” culminates neither in a climactic act of rebellion nor a moment of eureka by the protagonist. In fact, Kathy, the narrator, has had a vague sense of her tragic fate — her death — ever since her childhood, a fact that is implied by the undertone of distress that pervades the entire novel. In this way, Ishiguro manages to portray Kathy’s emotions in a way that is more controlled and complex than a simple, sudden outburst of her despair. Perhaps even more worth noting, however, is the way in which Ishiguro depicts the scene in which Kathy imagines her life as a mother, with her baby cuddled up within the embrace of her arms. Then again, this scene is not entirely unrelated to Isiguro’s narrative style, as it harkens back to Kathy’s knowledge of unsaid facts — specifically, the fact that organ donors are incapable of conceiving or marriage, as they are fated to end their lives prematurely. This scene, coupled with the lyrics of the song “Never Let Me Go,” is perhaps Ishiguro’s greatest appeal for his readers.

— Nancy Kim ’21

When we were kids, my sister and I loved to play “The Game of Life.” Stocking our miniature cars with armless pink and blue figures, we would spin our way around the board until, ideally, we arrived at Millionaire Acres: a collection of plastic retirement condos. This game essentially defines “life” as an “accounting of income and expenses,” historian Jill Lepore writes. What does a game like that, and its popularity in America from the 1960s onward, say about how we, culturally, define “life”? The question is a broad one, but it provides the basis for only the first chapter in Lepore’s wide-ranging, remarkable, and surprisingly lighthearted book, The Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death (2012).

The Mansion of Happiness — a reference to an 1806 iteration of “The Game of Life” which took religious salvation rather than a glitzy retirement home as its end goal — is a “history of ideas about life and death from before the cradle to beyond the grave.” Structurally, it echoes the life cycle: the first chapter narrates a brief history of the fetus, while the final offers a window into the cryonics movement (the practice of freezing the corpse to preserve it for resurrection). In between, Lepore delves into everything from the history of breastfeeding to the rise of the parenting-advice industry. She finds her characters in disparate, unexpected places: we meet Lillian Gilbreth, a mother of twelve who built her career developing a science of housework efficiency while refraining from doing any housework herself; Slyvester Graham, who invented the Graham cracker and drew audiences in the 1830s for his diatribes against sex and alcohol; and Leonora Piper, a famous medium visited and studied by William James. My favorite chapter describes a battle between author E.B. White and the influential children’s librarian Anne Carroll Moore: Moore fought to prevent Stuart Little from hitting the shelves of the New York Public Library. (Moore’s rubber stamp, “Not recommended for purchase by expert,” could spell obscurity for the books which she disapproved of; in the case of Stuart Little, she was finally overridden.)

Lepore’s book is history at its readable best, using concrete episodes and characters to make a larger argument about some of the most enduring questions we face. The book is both casual in tone and clearly well-researched — according to an interview in the New York Times, Lepore racked up $6,000 in overdue library fines (!?) at Harvard’s Widener Library before writing the book. “This is, above all, a book of stories,” Lepore writes in her preface; in turn, her stories are many windows into the elusive “mansion of happiness,” plastic retirement condos aside.

— Audrey Spensley’ 20

Witches are in these days. We’ve gotten reboots of Sabrina the Teenage Witch and Charmed, and word is that a Hocus Pocus sequel is on its way (you’re up next, Twitches!). Latest on the broomstick bandwagon is Hayley Kiyoko, a religious figure in her own right. Kiyoko’s music video for her new single “I Wish” draws heavily from Netflix’s Sabrina, each character dressed in the quintessential school-girl plaid with collars sharp enough to slice up some magic herbs. The video opens as Kiyoko and her friends (ft. Maia Mitchell of The Fosters and Madison Pettis of cinematic masterpiece The Game Plan) perform a spell for Kiyoko’s crush to like her back. Complete with a mysterious potion, rhyming chants, and hand-holding in the shape of a pentagram, the spell is satisfactorily spooky and transports Kiyoko into a smoky candlelit room where she and other witch friends dance frenetically as if possessed (shoutout to Anze Skrube for some fantastic choreography). When Kiyoko’s crush finally appears, her button-up shirt dishevelled and tied in a knot above her skirt, she is the Baby One More Time Britney to Kiyoko’s Sabrina, inviting Kiyoko into new realms of what women who refuse to conform can do (as well as affirming the power of a solid button-up). Although the song itself might not be as good as the video, I’ll take any reason to see Kiyoko’s induction into one of femininity’s oldest, queerest, and coolest societies—or rather, covens.

— Sylvie Thode ’20

Stephen Hawking was one of the greatest minds of the last century. Brief Answers to the Big Questions, which was released several months after his death in 2018, is his final work.

Composed of material Hawking was working on and reflections from his personal archive, the book explores “big” questions all of us have wondered about, including “Is there a God?” “Is time travel possible?” and “Will we survive on Earth?”

Much of the book is based on hard science, especially the sections concerned with black holes, the subject of much of Hawking’s work during his lifetime. These Hawking breaks down in plain terms that are engaging and enjoyable to read, seasoned with examples, analogies, and even Hawking’s dry sense of humor. However, Hawking is clear that science has its limits. There is much we have yet to understand. None of the questions Hawking answers can be solved definitively.

What makes the book fun, then, is that Hawking fills these gaps with discussions of his own speculations and beliefs. Along the way, Hawking provides details about his childhood, career, and experiences living with ALS. He also displays convictions that are by turns wary and stubbornly optimistic about the future of the human race. Hawking possesses a deep faith in the power of science to save us from runaway climate change, overpopulation, mass extinction, automation, and a nuclear disaster — that is, ourselves. But we must wake up and focus, he tells us.

Hawking ultimately emphasizes the need for science education — not only for the sake of encouraging young people to pursue careers in science, but to promote scientific literacy in general. He warns that a lack of this literacy is becoming ever more dangerous in our increasingly technologically complex world.

It is this conviction that brought us his popular-science works, and it is for this reason Hawking’s book makes for a smart addition to your beach reading this very, very hot summer.

— Julia Walton ’21

It was almost an accident that I ended up at a wonderful production, Les Folies d’Offenbach, in Montpellier, France. I have never been to an opera nor did I know who Offenbach was, but I was in the city, and it seemed interesting so I showed up with limited proficiency in French and no idea what the show would actually be about. The production lived up to its name, delivering madness (les folies) and absurd comedy that was enjoyable in spite of (or perhaps in part aided by) all of my confusion.

This production took various pieces by Offenbach and strung them together into one performance, with the disconnected songs somehow fitting perfectly into the setting of a public pool as it becomes more and more bizarre and dream-like. As described by Marion Guerrero, who created the production design, “En effet, le lieu donnerait une cohérence à l’ensemble à partir d’une situation donnée, d’un endroit donné. Voilà ce que je cherchais : un endroit où toutes sortes de rencontres improbables pourraient avoir lieu. Un endroit où peuvent se croiser des militaires en remise en forme, des duchesses venues reluquer les maitres nageurs, des couples qui se retrouvent dans les vestiaires et des nageuses synchronisées qui dansent le french cancan…”: “indeed, the location gave coherence to the whole, from a given situation to a given place. That’s what I was looking for: a place where all sorts of improbable encounters could take place. A place where you could meet soldiers, where duchesses come to watch the swimmers, couples find themselves in the locker room, and synchronized swimmers dance the French cancan.”

The setting allows for some cohesion to the comedic madness, but the pool further serves as an otherworldly space of nostalgia. It feels more like a musical than an opera, with its Singin’ in the Rain-esque yellow raincoat and 80s/50s/20s nostalgia (following the 30 year cycle trend of nostalgia), reflected in old synchronized swimming shows and costumes. I’m sure that I missed some references since I could not have recognized any French ones nor am I familiar with how French 80s nostalgia differs from American nostalgia. Regardless, I found the effect of drawing on nostalgia to create an otherworldly, absurd, dream-like state to be fascinating and enjoyable. This dovetails with the current 80s nostalgia trend, especially with the recent release of Stranger Things 3, which seems to draw more on the escapism of nostalgia to create an aesthetic rather than a purposeful and comedic separation from our modern reality.

— Kate Kaplan ’22

Over the last couple of weeks in Sonipat, Haryana, I have been learning about the Indian Partition: the act that divided the Indian subcontinent into India and Pakistan and displaced about 20 million Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs in what was to become the largest mass migration in human history. This period in history was marked by horrific violence — with pillaging, massacres, and rape becoming commonplace — resulting from the fear, hatred, and, above all, an irreconcilable “otheness” that each group had learned to associate with the others.

Many writers and artists attempted to make sense of this tragedy through their work, but the voice of Saadat Hasan Manto stands out in its stark and unflinching gaze at the reality of Partition. Manto, who was compelled to migrate to Pakistan after hearing about and witnessing communal violence against Muslims in India, creates tight and unforgiving narratives which strip away Hindu and Muslim labels and instead depict the atrocities humans are capable of both experiencing and committing when circumstances give them the license to do so. His writing is frightening and graphic (in fact, he was put on trial multiple times against charges of obscenity) but also revelatory: Manto’s stories show us a side of the Partition that historical documents and statistics cannot make clear to us. They refuse to romanticize or inject false hope into their narratives and instead force us to confront the uncomfortable truth that morality does not always win out in dire circumstances and that we cannot know how we will behave when we are desperate, angry, and moved to hate.

— Mina Yu ’22

Hailed as “one of America’s least famous great writers,” Richard Yates has seen a recent resurgence in popularity. Though his first novel Revolutionary Road was a National Book Award finalist, Yates’ entire oeuvre was out of print by the time of his death in 1992, and the writers Yates inspired, including Kurt Vonnegut and Tobias Wolff, went on to surpass him in fame. Yates is thus an alluring figure to aspiring writers — he is proof that cream doesn’t always rise to the top.

Piqued by this history, I delved into “Doctor Jack-o-Lantern,” which follows a child struggling to make friends at a new school. In Yates’ simple, precise prose we see his characters’ different desires. Vinny craves friends. Miss Price, the teacher, wants to help Vinny fit in. As Vinny acts out, she wants to discipline him. When companionship fails to materialise, he wants to hurt Miss Price and his classmates, who are mired in childhood cruelty.

Yates brilliantly sows and retrieves narrative threads, upending reader expectations in a way that doesn’t feel contrived. Several instances of misnaming represent how no one sees Vinny for who he is. When two classmates call Vinny his requested name and “[smile] at him in an eager, almost friendly way,” the reader feels hope for Vinny. Exhilarated by the attention, Vinny lies that Miss Price punished him with a ruler. But when she is kind to Vinny, these classmates turn on him. Yates surprises us again at the end, when Vinny returns to school to graffiti a lewd caricature of Miss Price.

Not for nothing was Yates christened “the supreme chronicler of American solitude”. After Miss Price encourages Vinny to participate during Show-and-Tell, the class watches in embarrassment as Vinny babbles on about a movie he hasn’t seen and parents he doesn’t have. During recess, Vinny ties his laces for something to do. It’s hard not to feel the fourth-grader’s pain when the well-meaning Miss Price says that “making friends is the most natural thing in the world.”

I’m sometimes underwhelmed by writers idolized by the literary world, but the mastery evinced by this six-thousand-word story proves that Richard Yates deserves every ounce of praise he’s received and more.

—Ashira Shirali ’22

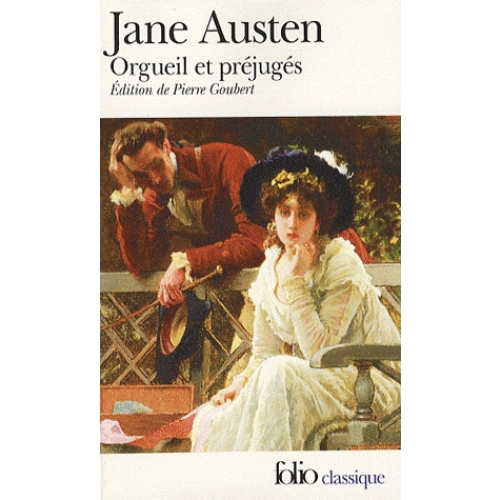

If neither the lovelorn characters on the cover nor the celebrated Jane Austen name are sufficient clues, I will state the obvious: the book I am enjoying right now is not new. In fact, published in 1783, Pride and Prejudice is about as classic a novel as it gets. It’s also not particularly new to me, considering it’s one of my favorite pieces of literature. However, there is something unique about my current perusal of the text. When I pull it out to read, the first word that I glimpse on the cover is not “pride”; it is “orgueil.” Recently purchased while studying abroad, Orgueil et Préjugés is a French version of the timeless Austen novel, translated by English Literature Professor Sophie Chiari in 2011. Although at first I was expecting a rote transcription, everything changed once I actually started reading. Since I have read Pride and Prejudice so many times, the plot points and character arcs are nearly as familiar to me as my own inner monologue. And yet, the nuances that I came to love in the original are substantially different in Chiari’s translation. Often, lovers of literature will say that great stories transcend language. I still agree with that; after all, the overarching, ironic tale of provincial English life and love has not been substantially altered. However, as I juxtapose the changed idioms, altered cadence, and my natural preconceptions of the French language with the purely English tale, I realize how fractured of an experience it is to closely read a story that was originally in a foreign tongue. It’s as if the entire novel is a synonym of the original, close enough to convey similar meaning and yet just unique enough to offer an altered delivery. It seems like my favorite classic can still surprise me.

— Nancy Diallo ’22

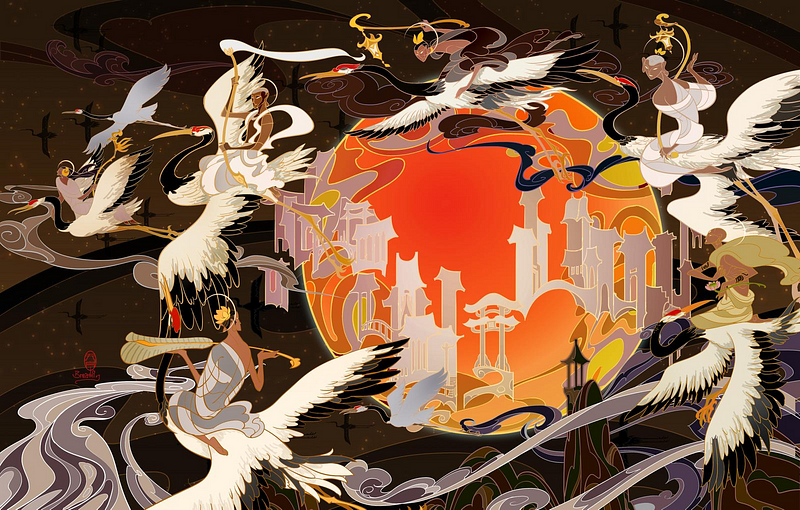

Jian Guo is a digital illustrator who drew the cover art for the Chinese editions of popular fantasy and science fiction novels, including those by authors like J. R. R. Tolkien and Brandon Sanderson. His art is extremely clean and elegant, combining the bright and flat colors of stained glass with the flowing lines and smoky curls of traditional Chinese ink paintings. The busy compositions are overflowing with details, particularly in the covers, which can fit all sorts of characters and setting details without overwhelming the viewer or looking cluttered. With the stylized figures and heavy use of symbols, his works can give the impression of illuminated manuscript art or tarot cards.

Jian Guo’s art can be found on his deviantART (breath-art) as well as his inPRNT (breathing2004).

—Sydney Peng ’22

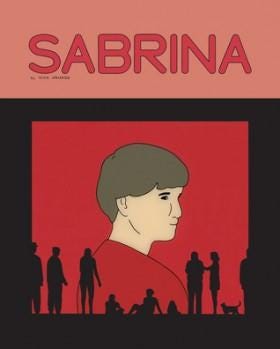

I might be a bit late to the party, but recently I finished Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, which was published in 2018. I am a fan of graphic memoirs (i.e. Fun Home and Persepolis) and novels (i.e. Ghost World, Building Stories, Patience), so when I came across a profile of Drnaso in The New Yorker, I knew I had to get my hands on his latest work.

The cover of the book is understated: the title in block letters above a bust of a young woman with short gray hair, etched in sparse lines. The red of her sweater bleeds into a background of the same deep, rich color. Silhouettes of people crowd the bottom of the panel in various states of action and repose, as if leisurely enjoying a photograph of her projected on a wall at a museum.

This kind of innocent observation morphs into a sort of twisted voyeurism. The story is told mostly from the perspective of Calvin, an Air Force airman in Colorado who welcomes his childhood friend Teddy after Teddy’s girlfriend, Sabrina, mysteriously disappears. Teddy is sullen and quiet, spending his days moping around Calvin’s home and listening to the radio — tuned into a program that seems to spout many of the same theories that fuel Pizza-gate believers and Sandy Hook deniers. For Teddy and Sabrina’s sister, Sandra, a real-life tragedy begins to turn into a farce for a dedicated group convinced that Sabrina’s disappearance is a sham, a cover-up, a conspiracy.

The artwork throughout is simple and an exercise in the fewest number of lines needed to convey the emotions of a grieving sister, or detached father. The story is anything but: for one, it helped me understand why New Zealand’s prime minister Jacinda Ardern refused to speak the name of the Christchurch shooter, or why there has been backlash against publishing the motives and manifestos of killers. Sometimes, knowing more is just that — knowing more — and you are left wondering what that hunger for information fed in the first place.

—Katie Tam ’21

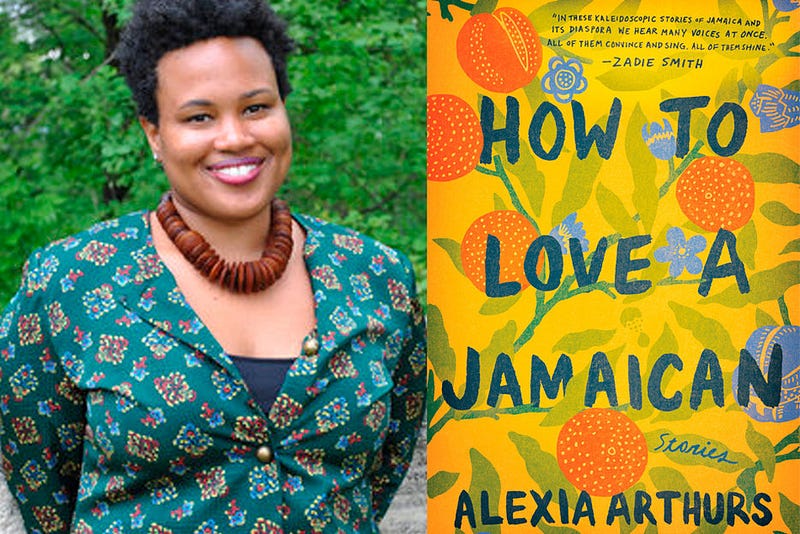

Be warned: Alexia Arthurs’s 2018 debut short-story collection, How to Love a Jamaican, will not teach you how to love a Jamaican, but it will show you the varied, lush, and painfully challenging experiences of Jamaicans across its diaspora. Arthurs features an array of stories of varying length and subject matter: there is a story of a teenage girl from Brooklyn who has been sent to live with her grandmother for her “bad behavior”; a young man who grapples with memory and self; young black girls with self-esteem issues; and a lesbian who tries to love freely despite growing estranged from her friends and family, among many more striking stories. In Arthurs’s story “Mermaid River,” there are nods to Jamaica Kincaid’s 1988 collection of creative nonfiction A Small Place, and in “Island,” Arthurs gestures to Nicole Dennis-Benn’s 2016 debut novel Here Comes the Sun. Not only is Arthurs carving out her own space within the lineage of Caribbean women writers, but she also engages thoughtfully and creatively with them, and with diasporic considerations. Ultimately, though, Arthurs’s stories are not only about love: How to Love a Jamaican also attends to questions of community, racism, class, and how one makes a home of themselves and with others.

— Rasheeda Saka ’20