Faces of Catastrophe, Faces of Liberation: Fazal Sheikh’s Independence | Nakba

BY STAFF WRITER SIMONE WALLK ’21

Fazal Sheikh,

Independence | Nakba

Photographer Fazal Sheikh’s Independence | Nakba explores the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by asking the viewer to bear witness to generations of conflict. Sheikh’s title alludes to May 14th, 1948, a day of dual significance in the region. In most Israeli communities, May 14th is marked by intense celebrations of nationalism. People of all ages dress in white and blue — the national colors — and dance in the streets, attending outdoor performances, singing, and reciting Hallel, the Jewish blessings of praise, typically reserved for biblical holidays. The celebrations of Israel’s existence are lively, joyous, and nearly universal, taking place in public streets and parks. Yet the 6.11 million Israeli Arabs and Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza, and Israel understand this day as the anniversary of the eviction of their people from their land. Nakba — literally, catastrophe — commemorates the 1948 War of Independence, when clashes between Israelis and Palestinians resulted in the displacement and forced migration of thousands of Palestinians. Arabs and Palestinians observe Nakba with demonstrations, collective mourning, and silent vigils. The dual names, histories, and narratives behind Independence and Nakba signify the two perspectives of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a conflict of interpreting and witnessing history.

In Fazal Sheikh’s Independence | Nakba (2013), the third and final portion of a series called Memory Trace, he uses the contested observance of the 1948 War to document the bifurcation of Israeli society. Sheikh, a photographer who focuses on human rights and migration, was invited to the region along with 11 other photographers for This Place, an exhibition initiated by photographer Frédéric Brenner. In an interview with Dr. Sheila Sheikh (no relation to Fazal Sheikh), a scholar of post-colonial studies at Goldsmith University London, the artist explained that Independence | Nakba emerged from his observation of “the extraordinary rupture of what the turmoil around the time of 1947/48 had created — a fissure within the society that is still palpable today. In all the time I’ve been there, this is what resonates with me the most: the idea of a scar just beneath the surface.” Sheikh identifies 1948 as the root of the societal bifurcation that now takes the form of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, using the metaphor of a societal scar to describe 1948’s impact on the region today. Independence | Nakba is an attempt to document this scar through portraiture, asking the reader to bear witness to the length of the conflict through a stream of faces.

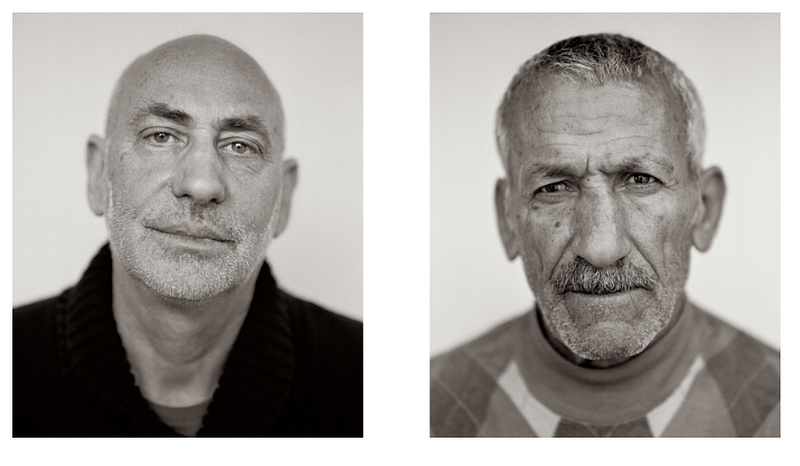

Sheikh’s 65 diptychs juxtapose two unlabeled individuals, one Israeli and one Palestinian, each born in the same year between 1948 and 2013, arranged from youngest to oldest. Sheikh’s subjects are unlabeled, and their ambiguous nationalities exhibit the arbitrariness of the all-powerful dichotomy between Israel/Palestine and Independence/Nakba — a crisis of both memory and nationality. Removed from one another by a thin strip of white paper, the subjects are sterile, calm, and stripped of context. Sheikh’s aging subjects ask the viewer to witness the passing of time itself, alongside the invisible memories and trauma that Israelis and Palestinians have endured since 1948. Each portrait represents thousands of individuals who were born in a given year, a commentary on the magnitude of the crisis of memory that is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Sheikh manipulates the sight of the viewer through his title and the diptych structure, establishing a dichotomy that prompts one to regard each diptych and wonder which portrait is of an Israeli and which of a Palestinian. The close-up headshots show people of similar skin color, dress, and neutral expression, like the adolescents below; each boy is dressed in stripes, with heavy brows, thick lips, bangs, and a prominent nose. Stripped of the semiotic context necessary to assign nationality, the viewer is self-consciously compelled to attempt to differentiate Israelis from Palestinians. In making the viewer aware of their need to assign “sides” to each portrait, Sheikh’s resists depicting his subjects as a part of a larger group, implying that the binary of Israel/Palestine is a type of blindness, prohibiting one from witnessing an individual. Without labels of nationality, one can bear witness beyond the “sides” of the conflict.

Fazal Sheikh,

Independence | Nakba

Sheikh’s diptychs create a singularity of focus, as the viewer cannot physically examine both images at the same time. One must choose a single set of brown eyes to link with, and then switch to the next. Sheikh said these shifts in the viewer’s focus are “implicating us as page by page our empathy shifts from one side to another.” The structure of the diptych is an allegory for the impossibility of empathizing with both Palestinians and Israelis at once. In making eye contact with one of Sheikh’s subjects, an act of partial witnessing occurs, pushing the spectator to view the other side peripherally in the blurred photo on the other side of the page. The dance of one’s eyes from side to side is an allegory for the larger challenge of equal empathy for all parties to the conflict.

Sheikh’s subjects look back at the viewer, as if they reciprocate the viewer’s witnessing. Their gazes vary from sharp and skeptical to warm and wide-eyed, but it is their eyes above all that are Sheikh’s focus. The isolation of the eyes of one subject pushes the viewer to consider the extent that witnessing the people of Israel/Palestine is even possible. It is impossible to take on the perspective of the two sets of eyes on one page simultaneously — so different is their position in the complicated landscape of Israel/Palestine. One must cycle between two sets of eyes, before flipping the page and marking another year; that year is tangible and witnessable, unlike the scars or memories beyond each set of eyes.

The passage of time is inherent to Sheikh’s photos, as his subjects age from newborns to 65 year olds. Faces transition from smooth to weathered, hair from wisps to locks to baldness, and clothing from charming childhood outfits to functional uniforms. 65 years after 1948, the conflict looks much the same as it did then; people on all “sides” have lived and died without a change in the political reality. With this progression of faces, Sheikh emphasizes the mortality of the affected parties in the face of a seemingly interminable conflict. As writer and literary theorist Susan Sontag wrote, “Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” Sheikh’s portraits freeze an arbitrary moment in each subject’s life, but by compiling them in the order of his subject’s ages, he renders each “slice” a moment in the static of political inertia, stretching from generation to generation. The white background behind the subjects remains unchanged as they age, symbolizing the entrenchment of the mired political context beginning in 1948. Sheikh’s subjects become allegories for all those who have grown up and grown older in post-1948 Israel/Palestine, pushing the viewer to see generation upon generation of conflicted memory and latent scars.

Fazal Sheikh,

Independence | Nakba

Sheikh elicits this human response from his viewer because his studio portraits appear more private than public. The first diptych of two babies, for example, is surprisingly intimate, as if the viewer has glimpsed inside a parent’s wallet, finding photos of the stranger’s children. These domestic, private photographs ask how the conflict has affected Sheikhs’ subjects as humans, in contrast to typical photography of Israel/Palestine, which often depicts violence or setting. The photograph of atrocity is shot by strangers for public consumption, and in the words of art critic John Berger, “offers information severed from all lived experience… The violence is expressed in that strangeness,” as viewers gawk in shock. While photos of violence remove the viewer from the events depicted, Sheikh’s intimate, private views of faces facilitate a reciprocal human gaze. Sheikh alters the discourse on the Israeli/Palestinian conflict through distance from its violence. Through employing the style of private photography and de-contextualizing his subjects, Sheikh opens a human conversation about Israel/Palestine.

Fazal Sheikh,

Independence | Nakba

Sheikh’s title frames Independence | Nakba as an inherently political work, where two sets of individuals become allegories for liberation and catastrophe. But Sheikh asks the viewer to witness the conflict through the aging of its constituents. The photographs consider the length of the region’s post-1948 reality, rendering people themselves monuments of history. As Sheikh’s subjects, stripped of context and calmly poised, compete for the viewer’s gaze, he suggests that objective witnessing of a conflict so vast in time is inherently impossible. One cannot hold the gaze of both eyes or hear both stories at once. It is in the slash between Independence | Nakba and the vertical white space separating the subjects of a diptych that neutrality lies. Yet Sheikh asks the viewer to pause in the eyes of each individual for a brief gaze, a recognition of the latent scars and many years of conflict buried within each fleeting face. Each face is forgettable, blurring into the one beside and all the rest that come before and after, a sign of the impossibility of adequately witnessing the cultural bifurcation of Independence | Nakba.