Identifying Calligraphic Genius

BY STAFF WRITER ABIGAIL MCREA ’23

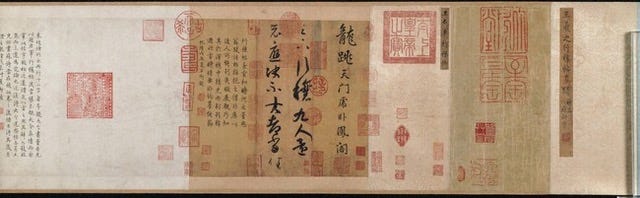

Ritual to Pray for Good Harvest,

Wang Xizhi. Courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum.

When looking at calligraphy, I do not instinctively perceive it as art. To me, a work of calligraphy is a beautiful piece of writing, satisfying in the same way a piece of notebook paper full of perfect handwriting may be. My outlook on this foreign art form began to change when I visited the storerooms of the Princeton University Art Museum this past fall. During the visit, I observed magnificent scrolls sprawled with brushstroke characters, landscapes, and ink splatters. The idea of handwriting as an art at first seemed foreign — the notion of it being an ancient’s kingdom’s main source of aesthetic pride even more so. Nothing is more academic in nature than text: I have been trained to take pride in the content of my words and to place less priority on their aesthetics because, as per traditional American logic, a text’s content is from where its meaning originates.

To the West, art is a realistic landscape painting, or an abstract burst of color. It could be a tune by Mozart or The Beatles, a beautiful work of pottery, or a carefully trimmed hedge. It is anything but text. In the modern world, writing means a block of 12-point Times New Roman font, either on its own or as a complement to a “true” piece of art — for example, a caption in a magazine. We live in a world where emotions are expressed through color and sound — a land where necessity and artistry are compartmentalized into separate fields. As a result, it is rare to walk into a museum and see a string of Latin letters in a display case. Keep walking through the same museum, however, and you will likely find an Asian art exhibition boasting its calligraphy.

When I first beheld Wang Xizhi’s legendary Ritual to Pray for Good Harvest, I was confused. The handwriting and the brushstrokes were majestic, but it was unlike any ‘art’ I was familiar with. Additionally, the literal meaning of the characters is unimportant to connoisseurs. They are a reference to ritual sacrifices that ancient Chinese society would perform before the harvest, but scholars are still unsure if this meaning is accurate. Ritual is instead prized for its aesthetic beauty. What must have been the ancient Chinese definition of art in order for the people to cherish something so mundane as writing so dearly? I pondered on this question for days, unable to reach a conclusion until studying Wang Duo’s Calligraphy After Wang Xizhi.

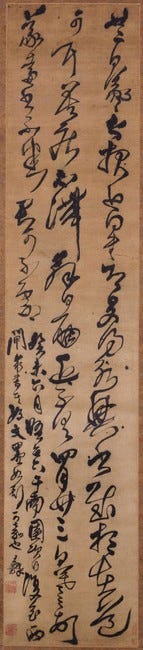

Calligraphy After Wang Xizhi, Wang Duo. Courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum.

What initially appeared to be scribbles on yellowed paper transformed into a profound flurry of emotional expression. I realized that the meaning of this work does not lie in the phrases but are instead contained within the ink splotches, the extraneous brush swirls, and the frantic placement of the characters. Wang Duo’s mission is akin to a pianist performing a Mozart masterpiece: he uses Wang Xizhi’s phrases and style as a medium for his own artistic output. In fact, Wang Duo completely focuses on the artistry of the writing, as demonstrated by how he “shuns faithful copying of classical texts, [instead approximating] them with little regard for readability, haphazardly omitting characters and entire lines” (Princeton University Art Museum). Wang Duo breaks the perception of writing as a container of semantics by merging aesthetics and meaning with disregard to the traditional, communicational role of text.

The more I think about it, the more I realize how humans have a natural tendency to make every-day necessities into beautiful things — to see the simplistic perfection in mundanity. For example, the mundane task of walking from place to place has evolved over the millennia into the great sport of track and field, and the necessity of food has been cultivated into the culinary masterpieces flaunted by Michelin-star restaurants. Wang Xizhi and his contemporaries broke this barrier in the field of handwriting by transforming it from a mere form of communication to a cherished art style. Wang Xizhi and Wang Duo’s works gave me a revelation: that the true definition of art is not paint, music, or sculpture; instead, it is how humans turn necessities into beautiful forms of expression.

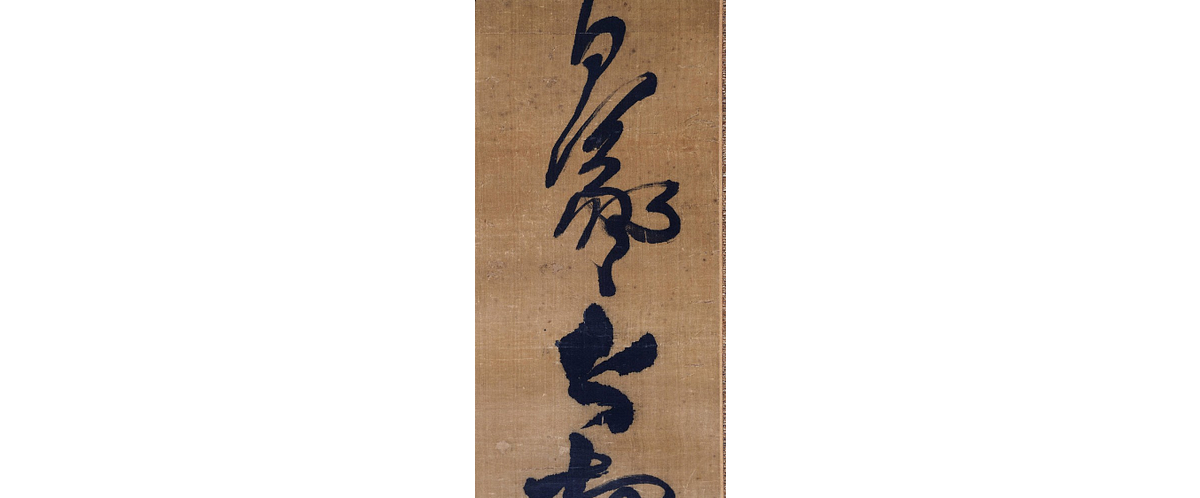

Close-up of C

all

igraphy After Wang Xizhi, Wang Duo. Courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum.

Works Cited

Calligraphy after Wang Xizhi, 1643. Princeton University Art Museum. https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/36654.